by Richard Telford

Author’s note: Though the product of many hours of research, writing, and revision, this chapter is nevertheless a draft; it will be subject to revision as the larger book in which it will appear takes shape. Still, I believe it begins an important process of bringing renewed attention to natural history writer and photographer Edwin Way Teale. Teale himself frequently published chapters of his books first in the popular journals of his day, such as Natural History, Audubon, Nature, and Coronet. I welcome critical response, either in the comment section here or through direct e-mail. I am grateful to the Archives and Special Collections staff for providing me the opportunity to share this work, and to the Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees for awarding me a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year so that this work could be undertaken. Contextual information about the project and manuscript can be found here.

Chapter 9: The Lonely Suffering of the Fallible Heart

A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”[i]

Stephen Crane, from “War is Kind,” 1899

Again and again, reason refutes the claims of worry; again and again, the rational mind points out the mathematical odds and the laws of averages—but again and again, the fallible heart returns to its lonely suffering.[ii]

Edwin Way Teale, March 22, 1945

The evening of April 2, 1945 began joyfully for Edwin Way Teale. It was an evening that affirmed his rising stature among the natural history writers of his day and perhaps, too, amongst the former-age titans he revered—Henry David Thoreau, John Burroughs, W.H. Hudson, and others. Two years earlier, he had accepted the John Burroughs Medal for distinguished natural history writing for his 1942 publication of Near Horizons: The Story of an Insect Garden. Now, two years later, he had returned to the American Museum of Natural History in Central Park West, New York, to look on as Rutherford Hayes Platt, a fellow Dodd, Mead natural history writer and photographer, received the Burroughs Medal. Platt’s 1943 This Green World was a book that in spirit, intent, structure, and design closely paralleled Grassroot Jungles (1937) and Near Horizons. Just as Edwin had suggested in 1937 that the amateur student of the insect world could be “like the explorer who sets out for faraway jungles” but do so in “the grassroot jungle at our feet,”[iii] Platt argued in 1943 that such wonders in the botanical world “were not rare nor discovered in a remote place, but were here all the time in the immediate surroundings of the everyday world.”[iv] That evening, Edwin noted later, “Platt pays tribute to my help in his acceptance speech.” He also celebrated his own election as “a Director in the John Burroughs Association” and expressed appreciation for the tenor of the evening, which “from beginning to end was in just the right key. I felt happy, enjoying every minute with no sense of impending doom.” It was “perfectly memorable.”[v]

The evening of April 2, 1945 began joyfully for Edwin Way Teale. It was an evening that affirmed his rising stature among the natural history writers of his day and perhaps, too, amongst the former-age titans he revered—Henry David Thoreau, John Burroughs, W.H. Hudson, and others. Two years earlier, he had accepted the John Burroughs Medal for distinguished natural history writing for his 1942 publication of Near Horizons: The Story of an Insect Garden. Now, two years later, he had returned to the American Museum of Natural History in Central Park West, New York, to look on as Rutherford Hayes Platt, a fellow Dodd, Mead natural history writer and photographer, received the Burroughs Medal. Platt’s 1943 This Green World was a book that in spirit, intent, structure, and design closely paralleled Grassroot Jungles (1937) and Near Horizons. Just as Edwin had suggested in 1937 that the amateur student of the insect world could be “like the explorer who sets out for faraway jungles” but do so in “the grassroot jungle at our feet,”[iii] Platt argued in 1943 that such wonders in the botanical world “were not rare nor discovered in a remote place, but were here all the time in the immediate surroundings of the everyday world.”[iv] That evening, Edwin noted later, “Platt pays tribute to my help in his acceptance speech.” He also celebrated his own election as “a Director in the John Burroughs Association” and expressed appreciation for the tenor of the evening, which “from beginning to end was in just the right key. I felt happy, enjoying every minute with no sense of impending doom.” It was “perfectly memorable.”[v]

The brief interlude of unrestrained pleasure that unfolded in “the Hall of the Roosevelt Wing”[vi] on that early April evening offered much-needed reprieve. It was a time marked largely by deep foreboding for Edwin and Nellie Teale as their beloved Davy, their only child, fought near the Siegfried Line during the final collapse of Hitler’s Third Reich. This fear had taken root in the elder Teales’ shared consciousness long before David’s August 1943 enlistment in the Army Specialist Training Program at Syracuse University, long before his transfers to Forts Benning and Jackson after the ASTP was disbanded, and long before his deployment as a Private First Class to the European Theater of Operations in the fall of 1944.[vii] Edwin would later characterize this fear as “the dread of seven years—from 1938 to 1945,”[viii] and it was a dread that consumed the collective consciousness of a generation of parents watching their children come of age during the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Italy and Germany—the future course of which became fully evident with the September 1, 1939 German invasion of Poland—and the apogee of Japanese Imperialism, made plain to the American public by the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The Teales’ dread is evident in a brief but poignant anecdote near the end of the eighth chapter of Edwin’s 1945 book The Lost Woods, a book that, for Edwin, would become inextricably linked to David’s wartime service and to his death.

In the aforementioned chapter, “On the Trail of Thoreau,” Edwin chronicles the final leg of a 1939 car trip during which he traced the famous river journey undertaken by Henry and John Thoreau exactly 100 years earlier. Henry Thoreau, in his 1849 A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, wrote in great part to memorialize John, who had died in excruciating pain in his brother’s arms three years after the trip, succumbing to tetanus. Edwin too, in The Lost Woods, would later recount a trip he and David took by canoe on Middle Saranac Lake in upstate New York. “The Calm of the Stars” would be the last chapter completed for the book’s first draft, written while David was declared Missing in Action in Germany. It, too, would later serve as a memorial. In “On the Trail of Thoreau,” Edwin noted how, one century after the Thoreaus’ journey, on September 2, 1939, “the Merrimack flowed as placidly as before around the great bend of Horseshoe Interval.”[ix] The world’s waters, however, were turbulent and troubled: “Thoreau’s September day had been one of comparative peace in the world,” while, “a century later, it was a time of fateful decisions, of onrushing war, of the breaking of nations.”[x] The conclusion of Edwin’s 1939 journey came one day after Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, one day before declarations by France and Britain of war on Germany, and six days shy of David’s fourteenth birthday.

Pulling into a filling station that evening, Edwin noticed the attendant, “a young man in his early twenties,” who appeared “silent and preoccupied” as he listened to a “radio […] shattering the Sabbath quiet, raucous with direful news.”[xi] Edwin’s description of this young man is telling. It stands in stark contrast with most of the book’s content, which largely lives up to its subtitle, “Adventures of a Naturalist,” and strays only rarely into social commentary or overt emotionality. Edwin wrote:

We spoke but a few sentences that morning. I have never seen him again. I don’t know his name. Yet, often he has been in mind and his face, like a stirring countenance seen under a streetlamp, has returned many times in memory. Under the blare of the radio, that late-summer Sunday, we were drawn together by a common uncertainty, by a common experience. Although we were strangers before and strangers we have remained since, we were, for that tragic moment, standing unforgettably together. I have often wondered about his fate in the years that followed.[xii]

Just as Edwin memorialized David in “The Calm of the Stars,” so too did he memorialize this nameless young man whose future now seemed to dissolve. In doing so with anonymity, Edwin likewise memorialized a generation of young men. In 1939, this could have been any young man, in any filling station, in any American town. Here was a precursor to the coming catastrophic loss of American youth, measured both in the immediacy of their foreshortened lives and in the collective sum of their futures that would never be. By 1944, when Edwin wrote this anecdote into The Lost Woods, America was fully at war, and the fear of such future events was fully realized.

In this young man who “had graduated college […] and hoped to get married soon,”[xiii] Edwin must have seen an image of himself as a young man coming of age in an America disillusioned by the horrors of the First World War, a war that slaughtered many of his contemporaries and drove the nation toward isolationism. More disturbingly, he must have seen by simple calculation the likelihood of his beloved Davy, nearing fourteen, being called to service four years later. Thus, the young filling station attendant embodied the frightening march of time: what was—the child, sheltered and naive; what is—the young man watching distant events shape his destiny; and what will be—an unwritten chain of events that, in a world hurtling towards global war, loomed ominously. Edwin later reflected again on the march of time—and its indifference to the individual—in a November 14, 1944 journal entry in which he described an afternoon research trip to the venerable Room 315 of the New York Public Library, its ornate, gilded ceiling framing at its center a 27×33-foot cloud-scape mural painted by Tiffany Studios designer James Finn Wall in 1911.

By November 2, 1944, Private First Class David Teale, having completed his stateside training at Forts Benning, in Georgia, and Jackson, in South Carolina, had arrived in England, the final training ground before deployment to the Western Front. Thus, the Teales’ anxiety, which had grown throughout David’s increasingly intense live-fire training at Fort Jackson, was heightened now by his inexorable path to the battlefield. Edwin wrote:

In Room 315, as I paused for a moment looking down the long expanse of green shaded lights and yellow varnished reading tables it struck me how unchanged everything was. Here David was overseas, a thing that has hung in the back of our lives like a menacing storm cloud, growing in size and drawing nearer—the thing that threatened had become—as in a dream—a reality. Everything should have changed—nothing external had. And so it would be if he were reported missing or killed—the world around would remain firm, intact, no matter how the world within dissolved.[xiv]

Seeking solace in the familiar, Edwin found instead the indifference of time, the universe’s lack of obligation to preserve his and Nellie’s beloved son. He could expect no intervention from a “Ruling Power of this universe” that was “not interested in anything so small, so unimportant, as a generation” sent off to pay “in one crushing sum…the debts of the fathers—as well as their sins.”[xv] David’s goodness and his promise would not spare him any more than dumb luck might, and this dismayed Edwin. And too, should David fall on the battlefield, his only monument would be the kind “erected in the secret places of the heart by those who loved” him, and “in time, those hearts too will be no more—all remembrance, soon or late, dies also.” The world would continue on, and “How soon it [would] be as though he had never been!”[xvi]

Edwin’s disillusionment offers an apt reflection of “The Age of Anxiety” in which he lived—a First World War notion that poet W.H. Auden articulated for a new generation in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1947 poem of the same title.[xvii] Humankind had plunged itself into global war for a second time in as many decades with many of the same principal adversaries. The most fundamental conceptions of “civilized” humanity were once again being systematically challenged and deconstructed, not just by hate-filled political rhetoric but by unprecedented slaughter of combatants and civilians alike. And it was into this slaughter that David, innocent of its creation, was being sent.

Worst of all, Edwin and Nellie Teale could only watch events unfold. “How helpless we are!”[xviii] Edwin declared three weeks before Christmas in 1944 while David fought “somewhere in France,” enduring devastating fire from German 88mm FlaK 18 anti-aircraft guns directed groundward. By 1944, it was well-known that a direct hit from a German 88 could shatter the armor of the once-seemingly-impervious “Matilda,” the British Infantry Tank Mark II,[xix] so one can only imagine—and do so with terrible inadequacy—the terror felt by exposed infantrymen falling under such barrages set to detonate above their heads and rain down red-hot shrapnel and flaming forest debris upon them. For David, one such attack—the gruesomeness of which the Teales would later get a full account from Frank Tushi, a schoolmate of David’s serving in his regiment[xx]—inspired a confessional letter home to his mother. On December 17, 1944, David wrote the following from “Somewhere in France”:

Once when I was under 88 barrage, I promised myself and God too that I would write you a letter and do a lot of explaining. While I was up at the front a few came pretty close. I did some tall thinking and made a promise to do some tall explaining. Every time I get a letter telling me how proud you are of my fine character and everything it hurts me because I know that you do not know everything. Do not think I am trying to make you feel bad or anything. That is furthest from my mind. However I feel that if I did die (I hope I never do in this war) I would not leave this earth with matters straightened at home. Therefore this is to comfort me more than anything else. Then when ever you write I know you write with full understanding.[xxi]

David went on to confess his “past deeds in the states,” specifically his stateside sexual relationships prior to departing for England. These, by 21st-century standards, and probably by the standards of his contemporaries, seem mild and ordinary. For David, however, they fostered misunderstanding—an overestimation by his parents of his character—and this distressed him. With one young woman, he confessed to his mother, “I went in for heavy kissing and petting. In fact, I came the closest to sexual intercourse I ever wish to come outside of marriage.” He went on to share a revelation that he did “not wish to,” but, he declared, “I must as I made a promise. I have endulged [sic] in self abuse known as masturbation for some time.”[xxii] I include this here not for its prurient effect but because it illustrates the extraordinary shared honesty and intimacy of David and Nellie, which mirrored that of David and his father, and even his grandmother, Clara Teale. To the latter, he would write the following day and reference these confessions, doing the same in a letter to his father one day after that. Both of these latter communications, however, lack the detail of the initial letter to Nellie, and in directing his full confession first to her, it seems that David hoped that she would, in turn, break the news to Edwin. David had expressed his deep admiration for his father six weeks earlier in a long letter sent to his mother by air mail from England: “I am glad that you think that I have dad’s qualities of character,” he wrote, “but I am afraid that I do not have enough of them. You know he is a great man and I do mean great in all ways. I do not think I could ever be as great as he.”[xxiii] For David, it was, perhaps, too painful to broach these shortcomings first with his father, but he could take solace in the fact that his mother could and would do so, allowing the three of them to “start out on an equal footing all together […].” In the closing lines of his December 17 letter to his mother, David expressed relief that now “no secrets are hid.”

For the Teales, the effect of David’s confessional letter must have been profound—not for the content of its confession but for the depth of character that prompted David to write it: for his honesty; for his shortfall estimation of his worth in the shadow of his father’s greatness; and, at its core, for the profound love he felt for his family. Such love elevated the need for forgiveness over the dread of shame. Such love could endure “no secrets.” For these reasons, the letter must have pained and humbled them greatly, especially because David might die before their responses could reach him. David’s brief but sufficient reference to the 88 barrage—harrowing enough to prompt his confessions—drove this latter point home and redoubled the despair and the helplessness that governed their days. David had seen the brutality of war. His heart had been, as Oliver Wendell Holmes famously characterized the effect of war, “touched by fire.”[xxiv] David needed to make peace with his parents and with himself, despite the fear and the pain of doing so. “I love you all so much that tears almost come when I have to write this to you,” he confided to his mother on December 17, but doing so, he added, had left him “much relieved.”[xxv]

While David felt initial relief at having confessed his transgressions to his parents, in the days that followed he also felt guilt for the pain his letter would cause and anxiety over the way in which it would be received and answered. On December 18, he wrote again to his mother, a short V-mail that began, “This is to continue my last letter to you. I have told you all my past ‘miss deeds’ so it would relieve my mind. Then I know that whenever you write again or when I next see you we will meet with full understanding and I can really lift my head again.”[xxvi] He assured his mother, “If God is good and I get home safe and sound I will explain personally what befell me. This is just in case I don’t make it. I am ever thinking of you.”[xxvii] To Edwin, he wrote a similar V-mail on December 19: “As soon as I wrote that letter I was honest again and could lift my head again….I will anxiously await a letter from you concerning this matter.”[xxviii] Not typical of his correspondence with Edwin during this time, David closed by attributing his future to the will of God, further reflecting the horrors he had experienced and his acceptance that he might, in coming days, succumb to such horrors: “If God wills it I will live to see you again. I hope and pray for a speedy end to this war but God rules all.”[xxix] Up the right margin, he quoted scripture: “I can do all things thru Christ which strengthen[e]th me,” a line from Philippians 4:13 rendered roughly in King James Version language. The significance of this would have been ominously plain to Edwin: David was readying himself, and his parents, for his potential death.

Two days before Christmas 1944, David wrote again to his mother. The effects of his confessional letter still weighed on his mind. “Again I have a chance to write you,” he began. “I hope you have received all my other letters, especially the one I wrote last.”[xxx] He informed Nellie that he was “writing this on a helmet while in position on the side of a hill. The weather today is extremely cold.” David expressed his belief “that this is the Germans’ last effort to drive. I sure hope it is. It seems senseless that they should so stubbornly hold out.”[xxxi] Without explanation, he stopped writing but continued the next day. The preceding night, he told her, “was one of the coldest I ever want to run across. I was one of the lucky ones and found a sheltered spot to sleep on a pile of straw. I had one blanket and I made the most of it.” He then returned to the subject of his confessional letter: “Now to continue where I left off—when I did have a chance to write back in our rest area, I did and that letter was my result. Well what is done is done so I will try and put it out of my mind and start being the boy you thought and wished I was like.” David noted how “very strange” it was to spend Christmas eve camped in an open field in war-torn France, “…but we will try to make the best of things,”[xxxii] he reassured his mother. The Teales, too, would have to make the best of a rainy Christmas morning when the weather reflected the mood of the holiday for them, absent David.[xxxiii]

David wrote again through V-mail on January 6, 1945 to let his parents know that he was “still alive and kicking,” informing them, too, of his being “transferred to B Company 1st Batt of the 346 Inf.,” where he had volunteered for a reconnaissance patrol. He wrote, “We patrol all night and ‘sleep’ in the day time. The work is not too bad and I like it better.”[xxxiv] David had sought this kind of specialization as early as July of 1944, while stationed at Fort Jackson. At that time, he had written to his parents asking them to forward his birth certificate and a set of recommendation letters so he could apply to more specialized branches in the Army. Nellie sent the requested documents to David on July 17, 1944,[xxxv] and Edwin wrote to him five days later to confirm their being sent and to offer his thoughts on such specialization: “I hope the transfer works out if it is for the best. Nobody knows what is best to do but I suppose in the main getting into any kind of specialized unit will be a move in the right direction.”[xxxvi] One of the forwarded recommendations referenced David’s desire for “a transfer to the Army Air Corps.”[xxxvii] David’s ambition and intellect rendered general infantry training dull and unfulfilling. His intellectual restlessness, and that of a number of his peers in his former training group at Fort Jackson, was evident several months later. In a September 22, 1944 letter to his parents, he explained, “We can’t lay our finger on it but ‘we’ just can’t or won’t cooperate to the fullest extent. I guess we all have high enough I.Q. so that we ask ‘why’ when told something.”[xxxviii] Now, in January of 1945, having been deployed to Europe less than three months, David had created his own opportunity for specialization by volunteering for a Tiger Patrol, an elite reconnaissance group. It was a fateful choice, fraught with risk. Still, David closed his January 6, 1945 letter with words of reassurance: “Don’t worry to any great extent about me. I have just as much and maybe more of a chance of coming back all right.”[xxxix]

David wrote again on January 12, this time from “Somewhere in Belgium.” He affirmed the progress of the Allied Forces’ steady march to Berlin, and he shared again the news of his joining the Tiger Patrol. Such reiterations form a common thread throughout the wartime correspondence between David and his family, as long delays in the transmission of both V-mail and air mail into and out of war zones often slowed delivery times to more than a month. Thus the sender on either end could not know in a timely way what letters the intended recipient had or had not seen. This is illustrated when David wrote in this particular letter, on January 12, “I received your letters from the 24 Nov. to 26 Dec. It sure was a pleasure to receive so much mail at once, after such a long delay.”[xl] In his closing paragraph, David turned to self-reflection:

I could say so many things if I could see you folks and talk directly to you. Ever since 1945 I have felt like a new man. I think I shed a coat of old evils when I passed the New Year. I feel too that I have grown considerably in all ways. I hope I am correct. I still have not heard any response from my “letter of evils”. I hope you were not hurt too greatly. Be consoled that I have shed them and will try, with the Lord’s help, to be “the little boy mother wish [sic] I was.”[xli]

David’s combat experience had wrought profound and irrevocable changes upon him, but it had not stripped him of the boy within who wanted to please his mother and father. This fact, seven decades and too many wars later, should humble us. David should serve as a messenger in much the same vein expressed by World War I sketch artist Paul Nash. Nash wrote to his wife Margaret on November 13, 1917, from “the most frightful nightmare of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe rather than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable.” He concluded his letter as follows:

It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.[xlii]

David is gone but his words remain, and they can speak truth to us. All casualties of war should serve as such messengers, but, amidst the reiterations of mass violence that span centuries, they rarely seem to.

The reader of the wartime correspondence between David and his parents is not privy to Edwin or Nellie’s response to David’s “letter of evils.” In the Teale Papers, there is a significant gap in the correspondence sent by Edwin and Nellie to David. Their prolific wartime letters seemingly halt abruptly on September 15, 1944 and then resume on March 2, 1945, only thirteen days before David’s fatal Moselle River crossing. This gap in the record hurtles the letters’ reader nearly six months forward to David’s final days in a way that seems to highlight the suddenness and the prematurity of his death. Though no response by either of his parents remains, David, in a January 25 letter to his father, wrote, “I received your three V-Mails today. I mean The V-mails from all three of you. I am glad to finally learn that the understanding between us is now clear.”[xliii] The nature of their respective responses can likewise be surmised from the following entry in Adventures in Making a Living:

Today’s mail made me very thankful. Davy’s letter, giving his past misdeeds, came in and his mistakes were not so bad. We are, indeed, on a firm foundation. To have a boy of his fine character outweighs all else.[xliv]

No doubt, Edwin expressed such feelings directly to David, and Nellie and Clara certainly did as well.

David wrote on January 20, “It is very interesting to note that…you folks wonder what I was doing on New Years of ’45 for on that night I entered the new year with the exploding of German grenades. We were out on a reconnaissance patrol and we ran into a little trouble. However, ‘All’s Well that Ends Well.’”[xlv] David also described being billeted in a village in Luxembourg, noting that he was currently housed in “what used to be an old German café” where he and his fellow Tiger Patrol mates could “have a few of the luxuries of life.” In this interlude, he told his father, they did not “feel the war much,” though they “know it is around by first hand experiences.”[xlvi] Three days later David wrote, “We worked on the place and have now got it fixed up quite well. Of course we never know when we may move out. In the meantime we are enjoying our selves to the utmost.” In this same letter, he expressed his homesickness, writing, “Whenever I get a chance to daydream I try and imagine when I come home. This revives me and lifts my morale for a while.”[xlvii] For Edwin and Nellie, as for their beloved child, such morale lifts, so desperately needed, were likewise short-lived.

By February 18, David’s unit had left Luxembourg, and he wrote to his family from “Somewhere in Germany,” though, based on Frank Tushi’s account, he may instead have been in Belgium at this time, west of the German border.[xlviii] Absent is the lighthearted tone of his letters written while billeted in Luxembourg, for with the end of that billeting also came the end of his patrol’s short reprieve. Though his language is measured, his frustration over the disparity between home front perception and Western Front reality is evident:

You seem to be very optimistic about the war. From all reports from the home front every one seems to think this war is just about over. I sure hope you are right. However, we who are dodging German bullets don’t seem to think so. We hope so and the fact seems to grow stronger each day yet “they” still are firing.[xlix]

In this letter, David also corrected what presumably was his parents’ speculation in a previous letter about his entryway into Germany, but his reference to their speculated entry point was redacted by an Army censor. “I can not tell you yet how we did come,” he explained, nor would he, though the Teales would later learn much about David’s final months from Frank Tushi.[l] In his February 18 letter, David likewise answered their presumed inquiry about photographs he had taken while deployed, writing, “The films I took are in a duffle bag that is some where. I do not know where and I doubt if I will ever see it again.”[li] Ten days later, in a separate letter, David speculated that the duffel bag, which also contained his camera, might be back in Metz, France, but he was not sure.[lii] Some of the contents of this duffel bag, including David’s camera, were shipped to the Teales the following October, arriving precisely one year to the day after his last furlough home.[liii]

Perhaps the lost correspondence was culled as a practical matter when David’s personal effects where shipped home, or David might simply have discarded it after reading. Still, reviewing the remaining correspondence nearly three-quarters of a century later, the questions surrounding the missing letters serve as a microcosmic iteration of the unanswerable questions surrounding the events that unfolded after midnight on the Moselle River. In turn, such questions are amplified to varying powers for each life lost in war, for each moment of suffering known only to the sufferer, for each trauma witnessed and buried—with the dead or within the living. Amplify this further from the individual soldier to all affected, and how clear it is that such a number defies calculation. “I am thinking of you whenever it is safe to let my mind wander,” David concluded his February 18 letter,[liv] and inevitably such wandering returned him to his Park Avenue, Baldwin home, and the shelter of his parents’ unconditional love.

* * * * * *

After fighting in the closing days of the Battle of the Bulge, primarily near Bastogne, Belgium, David’s regiment returned first to Luxembourg then reentered Belgium a second time. There, at Manderfield, west of the Siegfried Line, they remained until the beginning of March, when they began a push into Germany, crossing the border and driving east to Stadtkyll, where David captured a Nazi flag that he later sent home.[lv] Edwin wrote to David on March 2 from The Carpenter Hotel in Manchester, New Hampshire, enduring the strain of the lecture circuit. He would present “a lecture before the Manchester Institute of Arts and Sciences” that night and would “be glad when it is over!” He added, “In 1939—on the very day England and France declared war on Germany—I stayed in this same hotel when I followed the trail of Henry D. Thoreau’s trip on the Concord and Merrimack!”[lvi] Reflecting on David’s peril as he fought in Germany, Edwin must have thought back to his brief and nearly wordless exchange with the young filling station attendant six years earlier. The “dread of seven years” was now fully realized, and, with great understatement, Edwin finished the letter’s opening paragraph by writing, “A lot certainly has happened since that day!”

Edwin encouraged David in the following paragraph to “Let us know, if you can, a little more about your work. We can take it.”[lvii] The Teales must have agonized over the degree to which David was suffering his traumas alone; in their youths, they had witnessed the coining of the phrase “shell shock.” Edwin would later reflect on his inability to listen to the song “When You Come Back,” popular during the First World War, because “such a song—too overwhelming to endure for years afterwards…would symbolize and resurrect a great, a sad, a tense, an enduring moment….”[lviii] Now, David lived such moments daily, and was scarred by them, but Edwin and Nellie, four-thousand miles away and helpless, could offer him no relief.

Edwin went on in his March 2 letter to inform David that he had just “turned in 14 chapters—approximately half—of the new book,” adding, “It was quite a struggle to get it done.”[lix] He had initially titled the book Days Without Time and referred to it as such in much of his wartime correspondence with David. After an early dinner with American humorist Will Cuppy and novelist and critic Isabel Paterson at the New York Herald Tribune cafeteria in November of 1944, however, Edwin decided to change the title to The Lost Woods.[lx] Four years later, Edwin would use the former title for a new collection of essays published in 1948. In it, he argued that engagement with nature could provide relief from “the trappings of time that disturb the thought and harry the nerves, that split the hours into hard, brittle fragments…”[lxi]—an especially poignant notion in the context of the Teales’ intervening loss.

At the start of March, 1945, Edwin had only three months to complete the last fifteen chapters of The Lost Woods, due to Dodd, Mead on June 1. The challenge of this formidable task was compounded by the fact that, less than a week after his return from Manchester, Edwin would depart for another lecture trip, this one in the American Midwest. He lamented to David, “I wish the lecture trip to Chicago, Grand Rapids, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Etc. was over and done with,” adding, “I always feel my lowest before I have to give a lecture and maybe I am in the doldrums on that account now.”[lxii] Maybe. This latter postscript echoes a simple, bracketed statement from an August 5, 1944 journal entry in which Edwin wrote, “I’m afraid I will never feel at ease among people.”[lxiii] The statement illustrates in plain terms a significant challenge of Edwin’s rise to fame, one that was exacerbated by the terribly public nature of the lecture circuit. Still, the reader of his March 2, 1945 letter might more readily link Edwin’s “doldrums” to “the alternating hope and despair”[lxiv] he and Nellie endured as they grieved David’s potential loss—a necessary emotional preparation—while clinging to the hope that he would return safely to them.

By March 8, Edwin was packed and ready for his Midwestern lecture tour. He wrote David a short note before departing. In it he expressed relief that the first half of The Lost Woods had “got by the Editorial Board of Censors at the publisher’s office.” Edwin added that he had just bought for David a Grenfell parka. Though he had just shipped it, Edwin suspected it might only “prove good protection—for the summer cold,” given the pace of mail delivery.[lxv] It was a parka that David would never receive. Nor would he receive the letter itself, as it, like all of the letters the Teales sent to David in March of 1945, was returned a month later, undeliverable, the envelope marked “deceased” in red ink script. This, in turn, was crossed out with pencil and replaced with “missing.” Thus, their outgoing correspondence to David for this short period, filed by Edwin upon its return, is preserved. David saw none of these letters. The Teales’ reassurances, their attempts to lighten their beloved boy’s spirits, their expressions of their admiration for him, their optimistic statements on the war effort—all were returned unread, unheard, out of step with the forward movement of time.

David wrote again on March 9, a more optimistic letter in which he reassured his family, “I am well and still in there pitching.” The “3rd Army,” he continued, “has really gone ahead. I sure hope our good fortune keeps up. God is the only judge in such matters.”[lxvi] The mood of the patrol on that evening was festive, perhaps because victory seemed close at hand:

The boys seem to be quite happy this evening. They are all singing their favorite songs. Maybe the “snapps” they have consumed makes them that way. However I am sober, as usual, and I feel their spirit. It really is something to hear a group of tired hard dough boys get some enjoyment out of group singing.[lxvii]

David’s sobriety echoes Edwin’s own fear that he would never feel at ease among people. While David expresses no obvious anxiety here, we are reminded of his exceptionality amongst his fellow soldiers, an observer of their fraternization but not a full participant in it. By principle he was an outsider, but one senses in this letter and in others that, while such a role left his father perpetually anxious, it provided to David moral relief amidst the horrifying tableau of war. It was, perhaps, his sobriety, mentally as well as physically, that allowed him to see that although the “German people that are left here seem to be all for the American ‘soldat,’ […] there is hatred in their unguarded moments.”[lxviii]

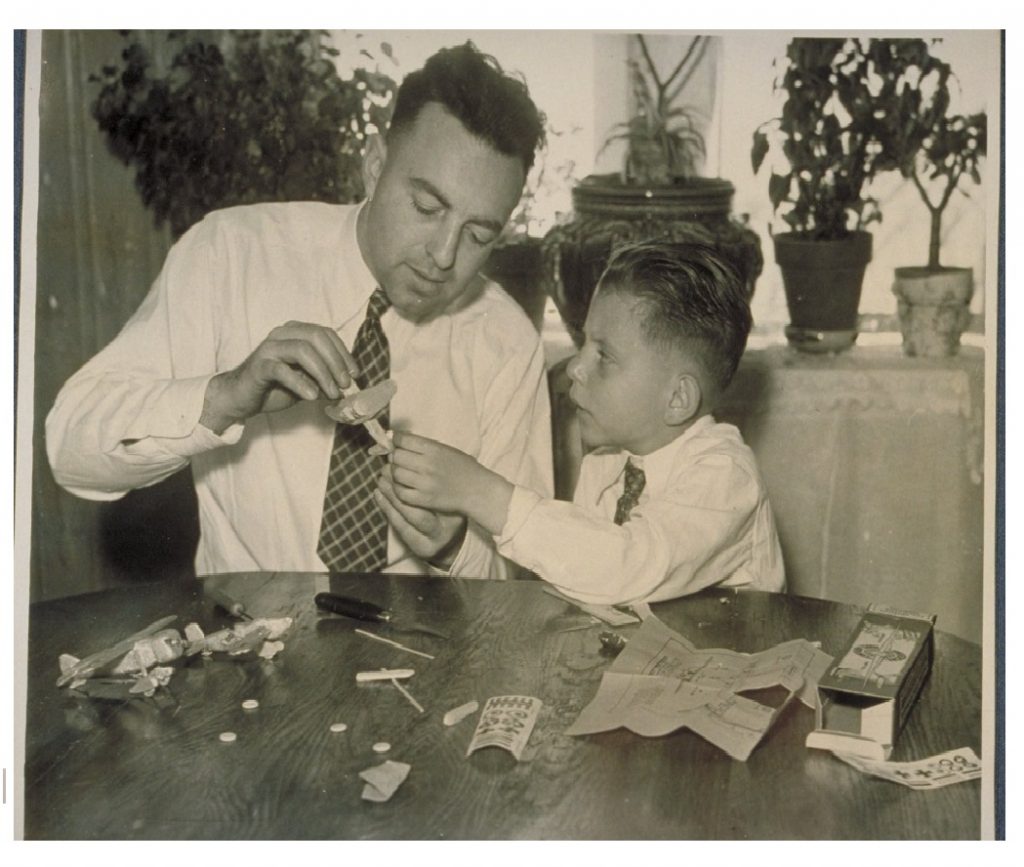

On March 10, David wrote two V-mails. In the first, addressed to his mother, he wrote, “Yes! There was a big push and I was in it. So far I am still healthy. I hope, with the will of God, that I remain that way thru out the war.” Along the right vertical margin, he added, “Got your Feb. 28 letter,” and this is the last correspondence received from his parents to which David refers in his own letters.[lxix] In the second March 10 V-mail, addressed to “Mom and All,” David informed his family that he had “had a chance for a rest,” adding, “We really needed it.” He wrote, too, of receiving a letter from Gertrude Selby, a neighbor and member of the Baldwin Bird Club. In it, David added, she “sent me a photo of you. I think it is a real picture of contentment.”[lxx] The picture certainly included both Nellie and Edwin, and possibly Clara Teale as well. “I was truly pleased with it,”[lxxi] David added.

Edwin wrote to David on the following day from The Stevens hotel in Chicago, still slogging through his Midwestern lecture tour. His presentation to the University Club had “went off perfectly,”[lxxii] he shared, which relieved him greatly, and he wrote of his plans to meet up with “Dewey Gunder—the boy who used to live across the road from Lone Oak,”[lxxiii] about whom Edwin had written in Dune Boy. Edwin then shifted his attention to the war. “The news from Europe,” he told David, “seems awfully good. Getting on the other side of the Rhine was a major miracle. It’s about time our side had some lucky breaks. Maybe they will all come at once!” He closed, writing, “We are praying that you are all right. The European phase of the war will be over by summer, I’m sure. According to present reports, combat troops are expected to have a three-week leave at home if they are shipped to the orient. Time will tell.”[lxxiv] It was the last letter that Edwin would write to David while the latter was alive.

On March 13, David sent a brief V-mail to his father, reassuring him that “Things are still running smoothly.” He added, “We have had a nice rest for awhile. I guess now it will be soon to move on again.”[lxxv] On the following day, March 14, in his final letter home, David confirmed this movement, writing:

We have moved from where I had last written you. Now we are closer to the Rhine in the most wonderful billets I ever hope to be in this side of the Atlantic. It is a town that does not seem to be touched by war at all. However we get in a few shells now and then to remind us there is still a war going on.[lxxvi]

David’s March 14 letter, addressed to “Mom and All,” is striking for many reasons. To begin with, it stands apart visually from most of the other letters in the file of his later correspondence home. He wrote on a sheet of lined newsprint paper, the kind on which students once composed rough essay drafts. The script—written with a fountain pen nearly drained of its ink—has a childlike sloppiness, and it looks like the correspondence of a young boy writing from summer camp, not a riverside encampment from which a reconnaissance patrol of twelve men will depart and only four return. The letter, in a haunting juxtaposition, expresses deep contentment. Comfortable billets seemingly untouched by war except for their vacancy offered physical and mental shelter. David spent the day leisurely “fixing and sorting [his] equipment,” noting, “It has been a grand opportunity in which to get organized.”[lxxvii] The contentment was not his alone: “The boys have all been in a much better mood of late. I guess things have been breaking better for all of us.”[lxxviii] The dramatic irony cuts deeply. As David Teale remains ignorant of coming events, we are not, and thus we are left more sympathetic, more deeply moved. We grieve for his coming death—for the wasted promise it represents—and for those who will bear the burden of his loss.

Near the end of David’s March 14 letter, he informed his parents, “I sent home a Nazi flag a few days ago. I don’t know how long it will take but I assume that it will take quite a while.”[lxxix] After David was declared Missing in Action along the Moselle River, this flag, on which sixteen members of David’s patrol had signed their names and noted their hometowns,[lxxx] enabled the Teales to begin their own search for information about their son’s fate. A number of the flag’s signers, like David, were declared missing on March 16, and the Teales would later reach out to the families of some of these men. But the events of this tragic sequence lay ahead, and, for the Teales, David was alive and well in mid-March. They suffered daily for his absence but hoped that he would soon return to them—the fall of Germany imminent—even if it were only for three weeks of furlough before shipping out to the Pacific Theater. In the early hours of March 16, their world was changed inexorably, but of this they knew nothing, and, for several weeks thereafter, nothing of their vigil appreciably changed.

Throughout the latter half of March, the Teales continued to send frequent letters to David, buoyed by the continuous flow of optimistic news of American successes in Germany. On March 18, Edwin wrote to David from the Hotel Schroeder in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, still plodding through the Midwestern lecture circuit. He was excited to have read in the Sunday paper “how the 87th Division had been the one that had captured Cobbling [Coblenz].” He noted, probably with great though cautious relief, that, according to the news story, the German “opposition was comparatively light.” He qualified this, however, writing, “…but then you probably know more about that than the reporter does!” He noted, “…things are looking better all the time in Europe,” and he hoped “it will be over in a few months.”[lxxxi] One week later, on March 25, Edwin wrote, “By all the newspaper accounts, you are in the middle of big things. We pray you are all right and that the big push this time will bring the end. It seems possible at this writing.” He concluded this short letter, “Keep your eyes open, Dave—we, too, are waiting for the day when you will come home.”[lxxxii]

Like David’s final letter home, Edwin’s final letter to his beloved Davy, written on April 1, 1945, Easter Sunday—the day before he would travel to The Roosevelt Wing of the Museum of Natural History to celebrate Rutherford Platt’s acceptance of the John Burroughs Medal—is deeply affecting. Like David’s final letter, Edwin’s affects the reader by its optimism. “I imagine,” he began, “this is the strangest Easter Sunday you ever spent. Hope it will be the strangest you ever spend, too…The papers are full of the progress that is being made. The ‘Golden Acorn’ division is mentioned whenever there isn’t a news blackout. We will be anxious to hear from you after the big push.”[lxxxiii] He noted also that David’s last communication, three weeks earlier on March 10, had referenced another letter to be sent by air mail, and Edwin hoped “we might get that tomorrow.” He likewise detailed their Easter morning, telling David, “We went to the first service that began at 9:30 a.m. We thought of you and I imagine you were thinking of us this Easter Sunday—that is as much as it was safe to think of anything other than the work at hand.” He expressed his “hope [that] it will all be over in a few weeks but no one can tell for sure.” He and Nellie were not, Edwin continued, “getting up any false hopes, but it will be a great day when it is over, and over right.”[lxxxiv]

As his April 1 letter progressed, Edwin looked to the future and wondered “how things are going to be rebuilt” following the war’s end. “But,” he concluded, “that will be the thing to work out in a long period of peace”[lxxxv]—a tragically naïve echo of the World War I catch phrase “the war to end all wars.” Turning to lighter matters, Edwin reassured David that the latter’s bicycle, “which gave out late last fall when I was riding it”—likely a reflection of the gas rationing that limited car trips to the Insect Garden—would be “in good working order—if the tires hold out—when you come back.” He also noted his inclusion of the clipped-out Saturday Evening Post “April Fool cover by Norman Rockwell with all kinds of things wrong with it. You may have some fun trying to see all the things you can catch.”[lxxxvi]

The cover, still folded into the two-page letter typed on onion-skin paper, features a balding man wearing the expression of a Shakespearean clown. The man sits with his back to a maple tree, fishing. He has skis on his feet, but bedroom slippers cover his leather ski boots. The maple tree yields apples, a lone baseball, and scattered pine boughs; on its trunk rests a shelf, and on that shelf a black telephone. Its handset hooked to the shelf edge, the cradle provides the platform for a bird’s nest sheltering Easter-colored eggs. The man, a golden halo above his head, wears a U.S. Navy lifebelt. He holds his fly-fishing rod backward, reel out, and is visibly flustered as he pulls a blue lobster from an open tomato can marked “PLUMS.” Dangers surround the perplexed fisherman, and, in this way, the viewer sees plainly the fine, juxtapositional line between humor and tragedy. Two alligators form the roots of the maple; a hooded cobra emerges from a mandolin that lays by the man’s side—but he remains ignorant, just as Edwin, trying to temper his son’s suffering with lighthearted amusement, was ignorant of what had already happened and what was to come. In all, Rockwell placed 51 oddities into the cover, and Edwin clipped and included in his letter the answer key for David’s reference. Examining the key closely, one can see faint, minute check marks penciled beside many answers, made by Edwin or possibly Nellie. David would never finish the remainder, and the lighthearted amusement of this folksy Rockwell puzzle would shortly thereafter give way to the terrible puzzle of David’s disappearance. The latter was a puzzle that Edwin and Nellie would spend 132 torturous days trying to solve, filling them with grief that, though growing more tolerable with time, they would struggle to reconcile for the remainder of their lives.

Edwin went on in his April 1 letter to share the news of coming days. He wrote, “Tomorrow night, I am going to the Burroughs Medal presentation. Rutherford Platt, who wrote ‘This Green World’ is to receive the medal this year. It seems so long, long ago when I got it—and it was only two years ago!”[lxxxvii] The reader of these letters cannot help but feel the impulse to postscript these lines with Edwin’s statement of March 2: “A lot certainly has happened since that day!” Edwin had made no progress on the remaining chapters of The Lost Woods, and he lamented, “A million and one things come up that interfere but they are things that have to be done.”[lxxxviii] After sharing some other Baldwin news, Edwin closed, writing, “I wonder where you will be when this letter catches up with you? Wherever you are, you know we love you and wish you all the luck in the world.”[lxxxix] These were Edwin’s last words written to his beloved son before the curtains of false belief and false hope were lifted by a 42-word Western Union telegram from U.S. Army Adjutant General James Alexander Ulio.

Two weeks earlier, Edwin had reflected, “At times when we least expect it, at times when we are most free in mind, when we are in the mental sunshine, [David’s] peril may be greatest of all.”[xc] Nine days after this entry—fifteen days after David had faced and succumbed to his greatest peril—on March 31, Edwin had received a letter from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, a rejection of his application for a Guggenheim fellowship to help fund the travel required for the completion of a book tentatively titled North with the Spring. In this book, Edwin ambitiously proposed to document an American season. Though disappointed by this rejection, his reaction was tempered by thoughts of David. He wrote, “But measured against the highest of all griefs—the loss of Davy—such disappointments are most minor matters. We are all still here and I will go on as before.”[xci] However, two days later, after a memorable evening spent in the Roosevelt Wing of the American Museum of Natural History—a time of great “mental sunshine” for Edwin—David’s peril was brought forcefully home. The storm cloud unleashed its torrent, and neither Edwin nor Nellie would ever again go on as before. On April 2, 1945, Edwin wrote in Adventures in Making a Living:

Coming up the stairs, I am calling to Nellie that I wished greatly she had been along to enjoy the program when the bombshell explodes. Nellie tells me to brace myself that David is missing in action in Germany! The telegram from the war department came in the late afternoon.[xcii]

The telegram, preserved in an acetate sleeve in the Teale Papers, reads:

THE SECRETARY OF WAR DESIRES ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET

THAT YOUR SON PFC TEALE DAVID A HAS BEEN MISSING IN ACTION IN

GERMANY SINCE 16 MARCH 45 IF FURTHER DETAILS OR OTHER

INFORMATION ARE RECEIVED YOU WILL BE PROMPTLY NOTIFIED.[xciii]

Forty-two words—188 characters—and the Teales’ world collapsed. “The first reaction,” Edwin continued in his April 2 entry, “besides numbness, was a small wave of relief. […]. There still is hope. But how much uncertainty these telegraphed words left in our hearts.”[xciv] In his Guild diary entry for the same day, in a separate postscript, he wrote, “A telegram from the War Department tells us that David is missing in action. I cannot write more.”[xcv] The words are blotted by droplets of water, the inked characters blurred into gray clouds on the page. They are the marks of tears, and only two of the remaining pages in the Guild diary for 1945 are similarly stained. They, too, mark a day of the most profound sadness. The bled ink is a monument to Edwin’s private grief, and to that of so many others. Even now, the “world around would remain firm, intact,” as Edwin had noted five months earlier, standing in Room 315 of the New York Public Library, but the shared world of Edwin and Nellie Teale, with David at its center, had, as they had so long dreaded, begun to dissolve, just as the fountain pen ink did on the diary pages.

In his longer April 2 journal entry, Edwin noted that he and Nellie could only “comfort each other as best we can through the night” and “try to remember the wise words of Marcus Aurelius.” He copied those wise words at the conclusion of the entry:

“Do not add to the facts—say: ‘My child is sick’—Do not go on to say: ‘my child may die.’”[xcvi]

Richard Telford has taught literature and composition at The Woodstock Academy since 1997. In 2011, he helped found the Edwin Way Teale Artists in Residence at Trail Wood program, which he now directs. He was a long-time contributing writer for The Ecotone Exchange. He was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant by the University of Connecticut to support his work on a book about naturalist, writer, and photographer Edwin Way Teale. The Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees likewise granted him a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year to support this work.

References:

Auden, Wystad Hughes. The Age of Anxiety: New York: Random House, 1947.

Stephen Crane. War Is Kind. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1899.

Gander, Terry. The German 88: The Most Famous Gun of the Second World War. Great Britain: Pen and Sword Military, 2009.

Gould, Harold F. Jr., Letter to Edwin Way Teale, 23 July, 1945, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “Memorial Day.” Speeches. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1896.

Nash, Paul, to Margaret Nash, 13 November 1917. TATE Britain, Archive. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/tga-8313-1-1-163/letter-from-paul-nash-to-margaret-nash-written-from-france-while-on-commission-to-make/2

Platt, Rutherford H. The Green World. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1943.

Schuman, Paul G., Letter to “To Whom it May Concern” [recommendation letter], 25 February, 1944, Box 217, Folder 5256, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, captured Nazi flag, circa 1944-1945. Box 219, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, Letters to Clara L. Teale, 1945, Box 216, Folder 2949, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, Letters to Edwin Way, Nellie Donovan, April to December, 1944, Box 146, Folder 2949, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, Letters to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 1945, Box 146, Folder 2950, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living: Volume II, unpublished journal, February 1944 to May 1946. Box 113, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary, 1945. Box 99, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan, Letters to David Allen Teale, 1944, Box145, Folder 2941, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan, Letters to David Allen Teale, 1945, Box145, Folder 2942, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Days Without Time. New York: Dodd, Mead , and Company, 1948.

Teale, Edwin Way. Grassroot Jungles. New York: Dodd, Mead , and Company, 1937, revised 1944.

Teale, Edwin Way. The Lost Woods. New York: Dodd, Mead , and Company, 1945.

Ulio, James Alexander, Western Union Telegram to Nellie Donovan Teale, 2 April, 1944, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Notes:

[i] Stephen Crane. War Is Kind. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1899.

[ii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 22 March 1945.

[iii] Teale, Edwin Way. Grassroot Jungles. New York, Dodd, Mead & Company 1937. 7,8

[iv] Platt, Rutherford. This Green World. New York, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943. 7

[v] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 2 April 1945.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Teale, Edwin Way, and Nellie Donovan Teale, Undated Obituary Draft for David A. Teale. Circa 1945-6. Box

146, Teale Papers.

[viii] Ibid. 6 April 1945.

[ix] Teale, Edwin Way. The Lost Woods. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1945. 81

[x] Ibid. 81

[xi] Ibid. 90

[xii] Ibid. 90

[xiii] Ibid. 90

[xiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 16 November 1944.

[xv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 18 August 1945.

[xvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 14 August 1945.

[xvii] Auden, Wystad Hughes. The Age of Anxiety: New York: Random House, 1947.

[xviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 5 December 1944.

[xix] Gander, Terry. The German 88: The Most Famous Gun of the Second World War. Great Britain: Pen and Sword

Military, 2009.

[xx] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 14 August 1944.

[xxi] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 17 December 1944.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 2 November 1944.

[xxiv] Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “Memorial Day.” Speeches. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1896. 11

[xxv] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 17 December 1944.

[xxvi] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 18 December 1944.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 19 December 1945.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 18 December 1944.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1944. 25 December 1944.

[xxxiv] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 6 January 1945.

[xxxv] Teale, Nellie Donovan, to David Allen Teale, 17 July 1944.

[xxxvi] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 22 July 1944.

[xxxvii] Schuman, Paul G., to To Whom It May Concern [recommendation], 25 February 1944.

[xxxviii] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 22 September 1944.

[xxxix] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 6 January 1945.

[xl] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 12 January 1945.

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Nash, Paul, to Margaret Nash, 13 November 1917.

[xliii] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 25 January 1945.

[xliv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 3 January 1945.

[xlv] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 20 January 1945.

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 23 January 1945.

[xlviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 14 August 1944.

[xlix] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 18 February 1945.

[l] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 14 August 1944.

[li] Ibid.

[lii] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 10 March 1945.

[liii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 15 October 1945.

[liv] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 18 February 1945.

[lv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 18 August 1945.

[lvi] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 2 March 1945.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 14 August 1945.

[lix] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 2 March 1945.

[lx] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1944. 14 November 1944.

[lxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Days Without Time. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1948. 1-2

[lxii] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 2 March 1945.

[lxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 5 August 1944.

[lxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 18 August 1945.

[lxv] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 8 March 1945.

[lxvi] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 9 March 1945.

[lxvii] Ibid.

[lxviii] Ibid.

[lxix] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, 10 March 1945.

[lxx] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way, Nellie Donovan, and Clara L. Teale, 10 March 1945.

[lxxi] Ibid.

[lxxii] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 11 March 1945.

[lxxiii] Ibid.

[lxxiv] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 11 March 1945.

[lxxv] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, 13 March 1945.

[lxxvi] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way, Nellie Donovan, and Clara L. Teale, 14 March 1945.

[lxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxix] Ibid

[lxxx] Teale, David Allen, captured Nazi flag, circa 1944-1945.

[lxxxi] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 18 March 1945.

[lxxxii] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 25 March 1945.

[lxxxiii] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, 1 April 1945.

[lxxxiv] Ibid.

[lxxxv] Ibid.

[lxxxvi] Ibid.

[lxxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxxix] Ibid.

[xc] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 22 March 1945.

[xci] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 31 March 1945.

[xcii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 2 April 1945.

[xciii] Ulio, James Alexander, to Nellie Donovan Teale, Western Union Telegram, 2 April 1945.

[xciv] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 2 April 1945.

[xcv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 2 April 1945.

[xcvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 2 April 1945.

Richard, this is amazing. I have never read any of the correspondence between Edwin and Nellie and their son but could feel for the boy with his need to confess his “weaknesses” to his parents so as to be on the same level with them in his mind when next they were together. What a tragic loss to those parents of such a fine young man, their only child. As an aside, do you have any idea why there is such a gap in the correspondence from 1944-1945?

[This comment written by Richard Telford]. Thanks for your kind words, Terry. Yes, the story of Edwin and Nellie and David, especially as it relates to his loss in the war, is a compelling one. They seem to have been extraordinarily close to one another. I suspect that the gap in the correspondence likely reflects the practical realities of the war; it is likely that David simply could not hold onto his parents’ letters in the field. If some of the letters were in the duffel bag in Metz, France (from which his personal effects were sent home), they might not have been determined to be of sufficient value to send home to those who had written them and already knew their contents. The final letters from Edwin and Nellie are preserved because they were returned to the Teales as undeliverable, and Edwin filed them carefully away, giving access to them now.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this.. my parents (ages 91 and 89) were friendly with Edwin and Nellie and I have many books signed by Edwin and letters between Edwin and my parents. I have placed flowers on David’s grave in Margarten Cemetery in the Netherlands. I see you direct the Artist in Resident program at Trailwood. Is there a donation I can make to that specific cause, perhaps as a gift for my dad’s upcoming birthday. I know he would be pleased. Again, lovely writing. Thank you so very much for sharing….

[This response is from Richard Telford] Thank you, Martha, for your kind response to this chapter. The story of the Teales’ loss of their beloved Davy is heart-wrenching, and it has truly been a privilege to use the materials in the Teale Papers to reconstruct for a present-day reader those difficult days. I continue that story in two additional chapters which have also been published on this site. As you have done, I hope to visit David’s military grave someday. There is likewise an inscription for David on Edwin and Nellie’s shared headstone in Hampton, Connecticut. Thank you as well for your generous offer to support the Artists-in-Residence program at Trail Wood. The program honors the Teales’ legacy in a way I think they would especially appreciate. A donation can be arranged through Sarah Heminway, who directs Trail Wood. She can be reached at the Connecticut Audubon Center in Pomfret. Thank you again for your kindness.