This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.

In June 1951, the Reverend Joseph Francis Donnelly sat before his typewriter, polishing the latest report on the Diocesan Labor Institute. As head of the organization, Donnelly had the job of documenting the institute’s work over the previous year. He covered everything from local chapter reports to national news to social events. The tone ranged from dull to depressing, punctuated only by Donnelly’s fierce passion for his work and a deep frustration with the lack of progress.

“Great segments of the working class know

nothing of the Church, and what may be more dangerous are wholly indifferent,” Donnelly lamented. The institute’s “puny efforts,” he feared, had only reached the fringes of organized labor in the state. “A vast neglected area,” he went on, “needs many hands, much effort, and much zeal.” After almost ten years, it felt like the institute’s work had barely begun.

In the early 1940s, Donnelly, then a parish priest in Waterbury, Connecticut, sought to organize an influential program of Catholic social teaching. Among the state’s workers, he found a paucity of knowledge about the Church’s teachings. In particular, he wanted to raise awareness about the papal encyclicals on organized labor and social justice. With support from the Most Reverend Maurice F. McAuliffe, Bishop of the Hartford Archdiocese, Donnelly organized the Diocesan Labor Institute to carry out his plans.

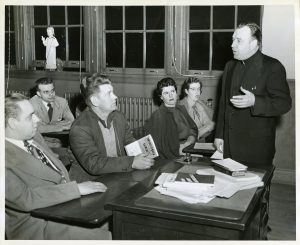

The institute soon established chapters in Connecticut’s major industrial towns, where local priests offered classes in Catholic social teachings and the rudiments of labor unions. It also sought to foster cooperation between workers and management as well as root out Communist influence in local unions.

The institute’s educational

programs initially proved successful. The director of each local chapter was free to organize programming as they saw fit. Most often this meant persuading a group of ten to fifteen workers to spend nights studying the encyclicals. At times, activities expanded to include presentations, forums, and radio programs. In the early years, chapter directors reported strong attendance, the number of local chapters grew, and the work gave Donnelly a sense of cautious optimism.

But there were challenges too. Overall attendance was low. Invitations to management were rebuffed. And local directors often could not find the time or resources to organize activities. As the years wore on, the greatest difficulty was the simple fact that many of the state’s labor leaders had already moved through the program. Donnelly and others involved in the institute responded by broadening their approach.

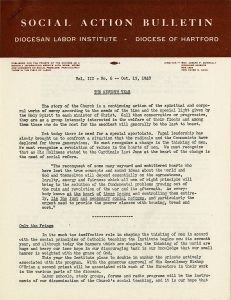

Beyond regular educational programs, the institute published the Social Action Bulletin. This small publication circulated among the priests and convents of the Hartford Archdiocese. It aimed to highlight the social philosophy of the Church and was well received, though it ceased publication in 1956.

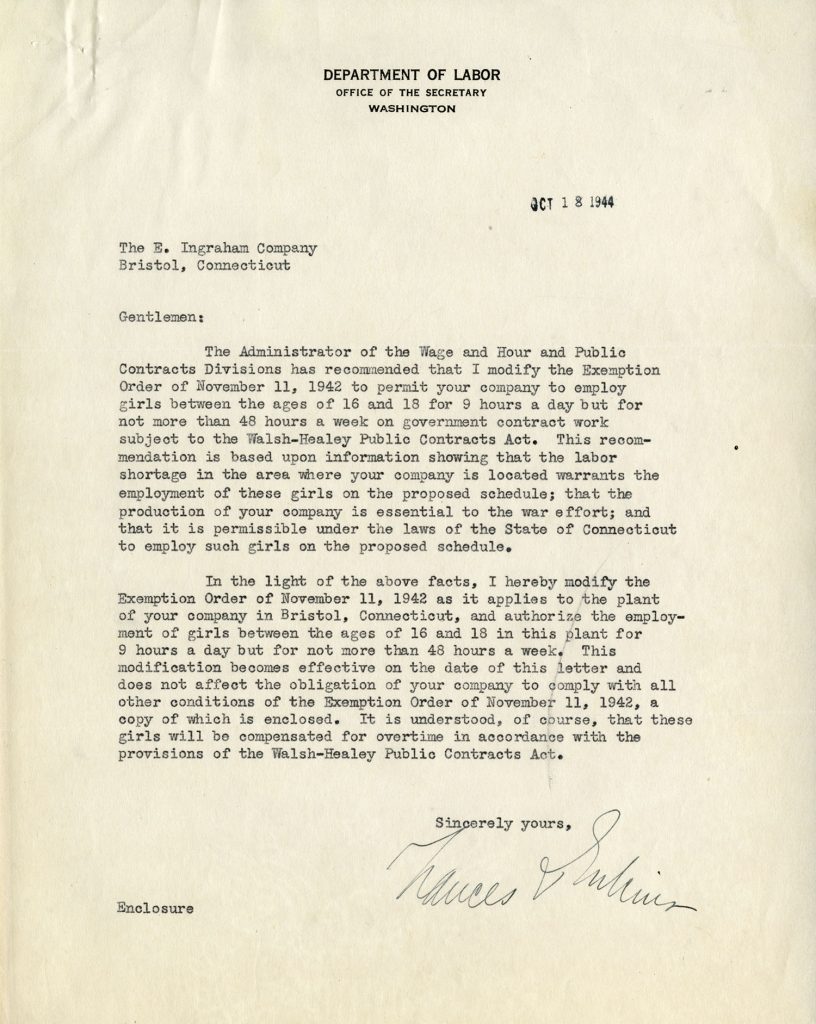

In addition, the institute held an annual Social Action Sunday beginning in 1949. A special day of observance, the event featured sermons emphasizing the Church’s social teachings and the institute provided a special pamphlet for church members. The number of pamphlets handed out could reach almost a quarter million.

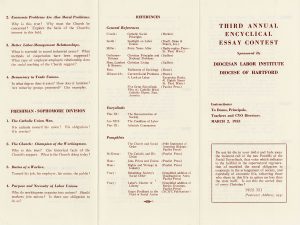

The institute also took steps to reach Connecticut’s working community outside of the church. One method was an annual essay contest held in local parochial schools. The institute convinced labor unions to provide a cash prize for the best essays on topics like the “Duties of a Worker,” “The Obligations of Ownership,” and “Profits and the Moral Law.” Around 2,000 high school and college students submitted essays each year.

In 1949, the institute began to give out the McAuliffe Medal Award to local labor and industry representatives who conducted industrial relations with a high moral standard. Named after Bishop McAuliffe, who died in 1944, the ceremony usually attracted around 500 people.

These various projects yielded modest victories, though not enough to temper doubts about the institute’s performance. In his annual reports, Donnelly did not hide his concerns. He warned local directors that they “must be reconciled to much energy and effort with scanty immediate results.” Their work could not be measured in quick returns, for as Donnelly had to admit, “an untroubled lack of interest makes our soil a stoney [sic] ground indeed.”

In 1954, the institute took a major step to revive its efforts. It conducted an extensive program of worker surveys in an attempt to connect with an ever-more aloof working-class. Over 1954-1955 and again in 1955-1956, local directors held a series of ten meetings with local labor representatives. At each meeting, the chapter director raised one of the survey questions and then held a general discussion on the topic. The discussions lasted for an hour or more, though most attendees felt they barely scratched the surface in that time. As usual, attendance was erratic. But the discussions themselves proved revealing.

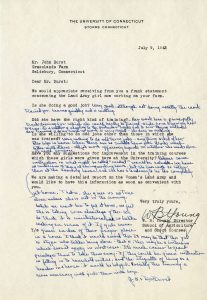

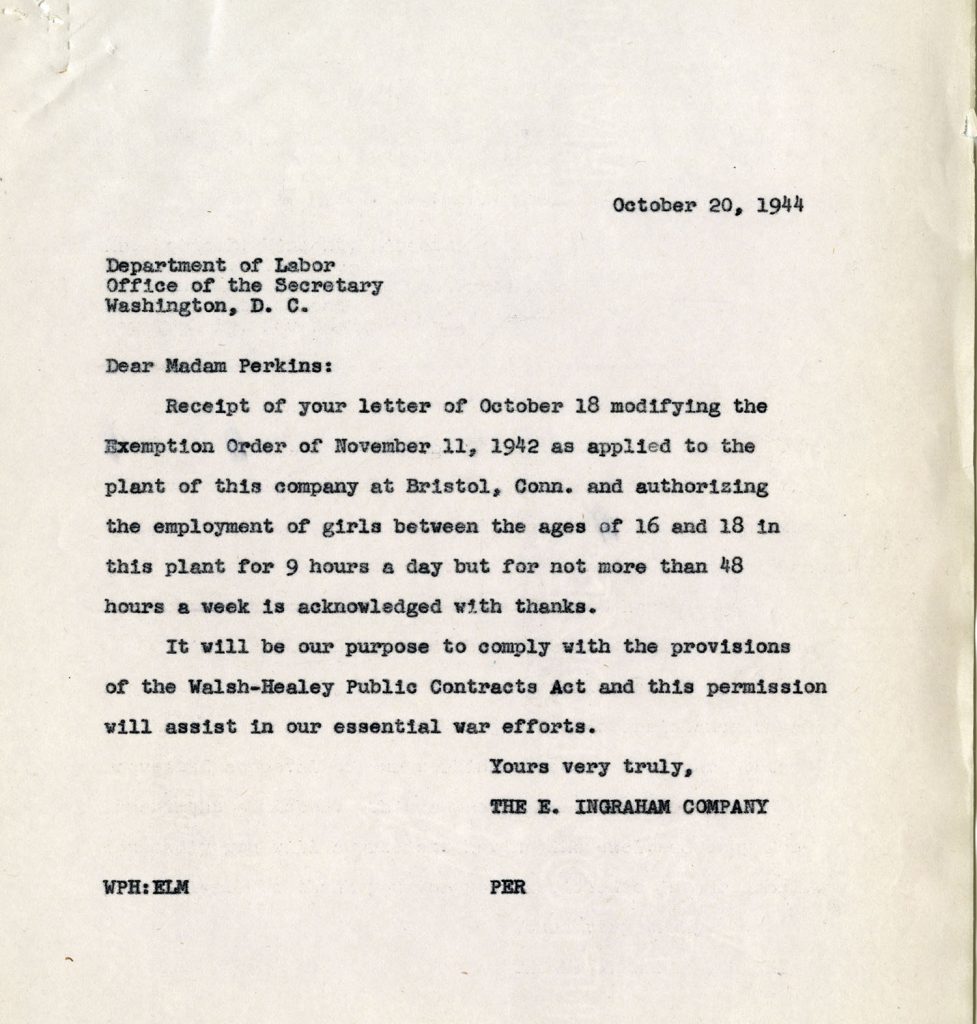

Pamphlet prepared by the Diocesan Labor Institute and handed out during their Social Action Sunday event (1956)

The questions could be narrow, such as “What do employees think of their jobs?” or “Are wage levels adequate?” Other times they were broad, like “What do workers think of religion?” or “What’s ahead for unions?” The responses usually left local priests equal parts troubled and confused.

In their survey reports, local directors complained that workers still knew little about Catholic social teaching. More disturbing, they showed no interest in learning. Chapter directors also bemoaned “a widespread ignorance” about union rights. Most workers, they noted, rarely attended meetings, cared only about good contracts, and preferred to let the union leadership take charge.

Pamphlet prepared by the Diocesan Labor Institute and handed out during their Social Action Sunday event (1956)

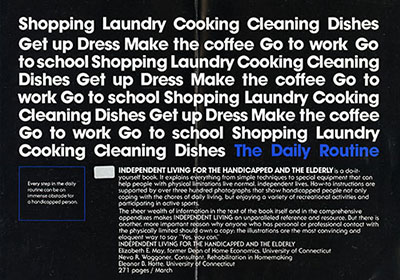

The directors were also surprised by what they heard. They learned, for instance, about the changing roles of women. “Strange as it may seem,” a priest from Naugatuck Valley wrote, “some women claim they have benefited from working outside the home.” The priests also registered a growing resentment over automation. The Bristol-area director quoted one worker as saying, “The pride in doing a thing well, in watching something take shape through our own efforts is going.”

The surveys generated a wealth of information about local workers. But it was not enough to shore up the institute’s faltering mission. Donnelly and the other parish priests soldiered on into the mid-1960s, often taking up other social issues such as civil rights. Still, their work became desultory, sustained only by the members’ commitment to Catholic social thought. Donnelly resigned himself to a community of workers “dulled by years of industrial prosperity and now with little concern for socio-economic problems.” In 1965, the Hartford Archdiocese made him Auxiliary Bishop, where he served until his death in 1977.