Stephanie Anderson is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Chicago and the recipient of a 2013 Strochlitz Travel Grant. Travel grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars and students to support their travel to and research in the Dodd Research Center’s Archives and Special Collections.

These days, when I’m thinking of a friend, I usually toss off a quick text or email. But a few weeks ago I stumbled upon a postcard image of Robert Burns’s cottage, and I had to send it to my mother, a Burns fan. The simple act of addressing and sending the postcard reminded me what a joy postcards can be; my mother would know right away why I had sent the card. Postcards anticipate some sort of response, even if it’s not a written one. In that regard, they are like poems – often understated, yet capable of signifying a great deal; sometimes intended for a particular addressee yet also circulating, exposed, in public. And like poems, their text is not their only means of signifying; it is generally only one component of the entire “message.”

The postcard’s other marks of distance – foreign stamps, the obtrusive postmark, the image on the front (which, as with the postcard to my mother, may be more “private” than the text on the back, as it can represent a mental placement of the addressee in the sender’s position or thoughts for reasons that an over-hearer/reader may not be able to intuit) – can be just as weighty. In other words, often it is the entire object or one of its components that signifies more than the epistolary text. As Derrida says, “What I prefer, about post cards, is that one does not know what is in front or what is in back, here or there, near or far, the Plato or the Socrates, recto or verso. Nor what is the most important, the picture or the text, and in the text, the message or the caption, or the address.”[1] The postcard tracks the movement of the sender, and confirms the fact that the other is still in the world.

Members of the group of poets known as the “Second Generation New York School” (active from about 1960 to the present) used postcards as a primary form of communication. The cards were printed en masse to advertise readings; they were handwritten en masse as invites to parties and celebrations. Presses printed individual poems on them to advertise books. For the artist Joe Brainard as well as others, they suited his interest in assemblage and his reclamation of kitsch. He tirelessly sent vast numbers of postcards, such that their saturation became, for their recipients, a form of articulating presence – and as evidenced in a letter from Bill Berkson, Brainard even considered starting a postcard company.[2] We can assume that for the group, the exchange of postcards can be seen as a form of playful conversation.

At the Dodd Research Center’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I had the  pleasure of looking through archives of several “Second Generation New York School” participants, including Bill Berkson, Ted Berrigan, and Larry Fagin. A chapter of my dissertation examines the epistolarity of Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, and so I was very excited to come upon letters and postcards throughout these archives.

pleasure of looking through archives of several “Second Generation New York School” participants, including Bill Berkson, Ted Berrigan, and Larry Fagin. A chapter of my dissertation examines the epistolarity of Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, and so I was very excited to come upon letters and postcards throughout these archives.

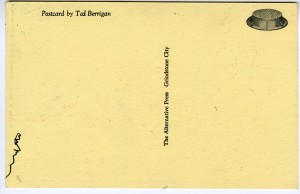

Berrigan wasn’t a prolific letter writer, but he did like postcards quite a lot; at the time of his death in 1983 he was working on a series of poems written on postcards. The poet and Berrigan’s widow Alice Notley reports that though these blank postcards were printed by the Alternative Press, they were 4½ by 7 inches, distributed in groups of 500, and given to other artists and writers as well.[3] The appeal of the postcard, Notley suggests, is its materiality; it is a “block”-like unit.[4] She explains how Berrigan used the postcard:

The postcard poem was a form dominated by the size of the card, though a relatively longer poem could be written on a card if Ted shrank his handwriting. Ted immediately used semi-collaboration as a way into the poems, inducing everyone he knew to write a line or draw an image on a postcard. He later eliminated the names of the “facilitators,” except for the occasional dedication. The poems are often epigrammatic, but are just as likely to be longer; they chronicle, not so explicitly, a difficult year…[5]

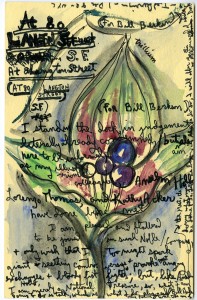

The Bill Berkson papers contain one beautiful example of such a collaborative postcard, which has a “trillium” in the background painted by Notley (the back is empty). According to a note in his papers, Berkson received the postcard in 1983, after Berrigan’s death.  The smooth and luscious lines of Notley’s watercolor flower provide an interesting contrast to the card’s text, which begins (after listing the address to situate the card’s production) “I stand in the dock in judgement / literally already condemned, but am / here to be informed…” The second slash is actually present in the text, insinuating that Berrigan conceived of the lines as poetry but perhaps a poetry still in a nascent or draft state.

The smooth and luscious lines of Notley’s watercolor flower provide an interesting contrast to the card’s text, which begins (after listing the address to situate the card’s production) “I stand in the dock in judgement / literally already condemned, but am / here to be informed…” The second slash is actually present in the text, insinuating that Berrigan conceived of the lines as poetry but perhaps a poetry still in a nascent or draft state.

The remainder of the text goes on to question groupings such as the “Second Generation New York School” tag that I employed above. Berrigan was at this point seen as central to the “group,” and here he name-drops other artists (Lorenzo Thomas and Kathy Acker) to poke fun at his placement vis-à-vis the public perception of the “group,” suggesting that aligning his own work with that of Lorenzo Thomas and Kathy Acker is a mistake. One aspect of their work’s reception, he says, is its ability to “provoke angry / exchanges + bloody fist fights,” an end his work cannot accomplish. He will, instead, simply attempt to communicate: “…so, what I am / going to do is talk, which is what I do plus read / my poems.” His “one word of advice” to Berkson, scrawled almost illegibly in the upper right-hand corner, is “Duck,” perhaps partially intended to pun on predictability. The image of the flower contains an upward trajectory in its lines, some of which guide the eye toward this right-hand corner, but semantics of the word hiding there suggest the opposite movement. “Duck,” as a verb: keep your head down, keep moving, don’t get hit by the incoming “bloody fist[s].”

I don’t take this statement to be apolitical, or against aesthetic provocation; I read it instead as a wariness of generalizing about groups and group labels. It is desirable to be included – or to have others included with you – in such grouping, even with the tongue-in-cheek tone (“I am pleased and flattered / to be joined in such noble / company,” he writes). But as in a boxing match, one can only avoid being knocked out (critically pigeon-holed and labeled, we might say) by remaining unpredictable, both in aesthetics and in perceived group affiliations. Hand-delivered to Berkson, it has a specific addressee, yet the suggestions Berrigan makes about aesthetic groupings seems directed toward a larger audience. Of course, he couldn’t have anticipated that 30 years later, a budding scholar would be thumbing through his correspondence looking for clues about his work and milieu – yet the postcard felt like it was intended to be overread by a recipient exactly like myself, in order to complicate and nuance conceptions of poetic form and coterie labeling

[1] The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 13.

[2] “United Artists Papers,” Archive (UCSD, n.d.), Box 1 Folder 9, MSS 0012, Mandeville Special Collections Library, UCSD.

[3] The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 12–13.

[4] “It’s a very graspable, manageable unit.” (See the introduction to A Certain Slant of Sunlight (Oakland, CA: O Books, 1988), n.p.)

[5] The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, 13.