Though it might not have seemed like it at the time, there were certain things to be thankful for during the winter of 1970. Storrs had seen its fair share of turmoil, to be sure, but the events of the late 1960s had not forced a closing of the university at any time. Even the fire of December 1970 failed to have the desired effect; although Colonel Richard DeKay admitted to the Connecticut Daily Campus that the incident was “a bit of an inconvenience,” military science classes continued as scheduled and repairs to the affected offices began the day after the fire. “I’ve been trying to get this placed remodeled,” DeKay joked as he sifted through the charred remains of his office. “I guess now it’ll be easier.”

Although things began to settle down during the 1970-71 school year, the continuous confrontations over Vietnam and other social issues raised by university groups during the late 1960s seemed to have taken their toll on UConn’s president. In October of 1971, Homer Babbidge tendered his resignation, stating that it was his time to pass “the baton of leadership” to someone else and denying that his leaving had anything to do with recent events. Whether or not that was true is difficult to ascertain; what is clear, however, is that regardless of the criticism he had faced from campus radicals during the late 1960s, Babbidge has retained his popularity with a majority of the student population. A petition asking him to reconsider his resignation garnered over 7,000 signatures, but to no effect, and Glenn Ferguson was appointed as the new president of UConn in May of 1973.

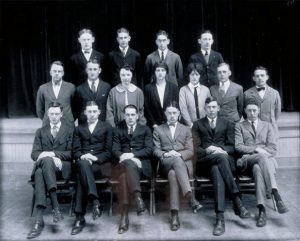

As always, changes to the university during this time were mirrored by changes to its Cadet units. This time, it wasn’t the introduction of a new branch, but a new gender that would forever change the face of ROTC. Until the late 1960s, female involvement in ROTC was primarily through auxiliary programs meant to support and encourage interest in Cadet training. One such program known as “Angel Flight” was active at UConn beginning in 1956. While those involved referred to one another using military ranks (the head of the chapter was known as a flight leader) and had some semblance of a uniform, they were not officially affiliated with the military. They served as hostesses at Air Force ROTC events, helped Cadets type term papers, and sponsored events like the annual military ball. While the organization still exists nationally today (now co-ed and known as Silver Wings), the UConn chapter appears to have died out sometime in the 1970s.

By 1969, however, certain administrative and legislative changes within the military meant that a number of jobs had been opened to females, and the demand for female officers increased significantly. Both nationally and at UConn, the Air Force took the lead in incorporating women into ROTC on a trial basis, and women were admitted to AFROTC units at several universities during the 1969-70 school year. The response was so overwhelmingly positive that the original plan of gradual integration was abandoned, and dozens of programs were opened to women by the fall of 1970.

[slideshow_deploy id=’6580′]It was about this time that UConn AFROTC had its first participating female Cadets, and in May of 1973 Ann Orlitzki became the first female Second Lieutenant commissioned through UConn ROTC. She would be followed the next year by Martha Bower and Mallory Gilbert, who also received commissions as Air Force officers. Army ROTC followed close behind; by 1972, at least one woman was participating in training, and the program’s first four female Second Lieutenants were commissioned in 1977.

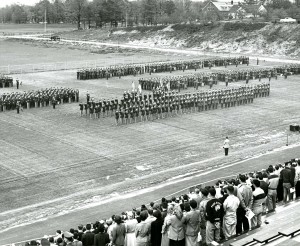

Even with the introduction of women, ROTC programs faced a sharp decline in enrollment during the early 1970s. The transition to an all-volunteer military, the decision by many land-grant colleges to make ROTC optional, and a pervasive anti-military atmosphere all served to decimate the ranks of Cadet units across the country; by one account, Army ROTC enrollment fell from over 140,000 to just over 38,000 between 1967 and 1975. In 1969, amid protests similar to those at UConn, Yale banned ROTC, leaving the Army and Air Force units at UConn as its sole representatives in Connecticut.

ROTC was therefore faced with the difficult task of maintain sufficient enrollment during a time when the military was an increasingly unpopular career choice. The obvious solution, far easier in theory than implementation, was to make the military more appealing to young men and women. While an increase in both the number of scholarships offered and the size of a Cadet’s monthly stipend were critical to this goal, changes to the daily on-campus life of a Cadet were even more beneficial in improving the appeal of ROTC. Haircut regulations were relaxed to allow sideburns, Afros, and haircuts below the ears, and many programs significant reduced the amount of time Cadets spent in uniform each week. Training was altered to focus less on the “spit and polish” subjects of drill and ceremony, and the traditional system of discipline through demerits was done away with, as were other forms of physical hazing and punishment previously considered rites of passage for new Cadets.

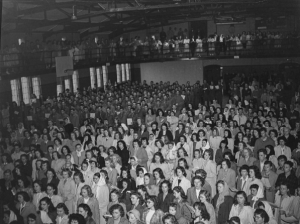

Campus Carnival, ROTC Hangar, 1978.

As intended, the relaxed environment and increased monetary incentives that came to characterize ROTC during the post-Vietnam period served to portray the program as less of a burden and more of an opportunity, and to blur the line between an ROTC Cadet and a normal college student. At UConn, the hangar provided a unique opportunity to improve relations between the university and the ROTC. Thanks to its spacious drill floor, it was used as a venue for a number of student activities throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, including carnivals, dances, and even “Beerfests.”

The ROTC reforms of the 1970s resulted to a rise in enrollment by the end of the decade. At many institutions, however, the outright ban on military training continued. Yale, for example, continued its no-ROTC policy well the 1990s due to the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy enacted by the Clinton administration in 1994, which barred openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service. Similar protests were raised at UConn, with critics of the legislation pointing out that exclusion of homosexuals from the military—and therefore ROTC—conflicted with the university’s policy against discrimination due to sexual orientation. Although an April 1995 vote by the University Senate proposed the phasing out of ROTC by June 2000, the recommendation was not accepted by the Board of Trustees. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was repealed in 2011, and a year later ROTC returned to Yale in the form of Air Force and Navy Cadet programs (UConn still has the sole Army ROTC unit in Connecticut.)

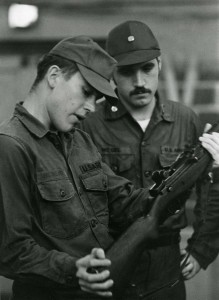

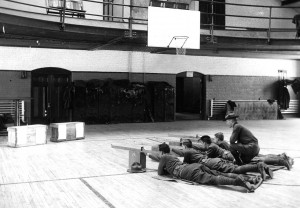

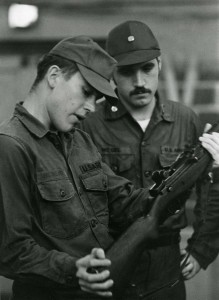

Cadet weapons have come a long way since the days of black powder muskets and bolt-action rifles. In this undated photo, two UConn Cadets examine an M14 Automatic Rifle, the standard issue infantry rifle for U.S. military personnel from 1959-1970.

Looking at the current ROTC curriculum, it is interesting to see what has changed and what has stayed the same. While the lax grooming standards of the 1970s and 80s have been replaced by a return to short haircuts and minimal facial hair, the uniform requirement has remained more or less the same; Cadets are required to wear their uniform while attending Military Science and Aerospace Studies classes and during leadership labs and field exercises, but spend a majority of the week in civilian clothes. As they have for decades, Cadets continue to spend several weeks in the field during the summer, with Army Cadets training between their junior and senior years at the Cadet Leaders Course (CLC) at Fort Knox, Kentucky (previously known as the Leadership Development and Assessment Course (LDAC), and before that “Advanced Camp”), and Air Force Cadets between their sophomore and junior years at Maxwell Air Force Base, Kentucky and Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

Currently, UConn ROTC benefits from a close relationship to the CT National Guard, which provides equipment and other support for Cadet training. In this 2010 photo, Army Cadets prepare to board UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters of the CTARNG’s 1st Battalion, 169th Aviation Regiment, which will transport them to a Field Training Exercise (FTX) at Camp Niantic, CT (Photo: Nick Hurley)

At UConn, the ROTC hangar, long a fixture on campus, was demolished in 1999, with the UConn Foundation Building quickly being built in its place. Both programs had moved out of the hangar the previous year, taking up residence in the former admissions building on North Eagleville Rd (now the Islamic Center, across from Swan Lake.) By the 2002-2003 school year, both programs had moved again, this time to their current homes on the third and fourth floors of Hall Dorm. Hawley Armory remained in use throughout this time, and is still utilized today; the court serves as a parade deck for Army and Air Force Cadets, and the building also houses the Army program’s supply offices.

After several decades of relative peace following the Vietnam War, UConn ROTC Cadets were once again faced with the realities of war following the terror attacks on September 11, 2001 and the beginning of the Global War on Terror. Many of those who commissioned through UConn, both before and after the outbreak of war, would go on to serve combat tours in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, and at least two Army ROTC alumni have to date paid the ultimate price for their service during this current conflict. Captain Jason Hamill (’98) was killed in Baghdad in 2006, and First Lieutenant Keith Heidtman (’05) died on Memorial Day 2007 when his helicopter was shot down in the Diyala province of Iraq.

Cadet Lieutenants Nick Hurley and Ashley Cuprak, both CLAS ’13, pose with Jonathan the Husky during a UConn football game at Rentschler Field in 2011 (Photo: Nick Hurley)

Several weeks ago, UConn Army and Air Force ROTC graduated its newest officers. Thirty-eight young men and women from the Class of 2016 put on Second Lieutenant rank for the first time and set out to begin their careers. Like their predecessors a hundred years ago, they cannot know what the future holds, but it is my hope that in reading these posts, they will now have a better understanding of where they came from, and the legacy that they, as UConn ROTC alumni, are now a part of.

It is a legacy that bears the names of thousands of Cadets who made their start at Storrs and went on to show the world the true meaning of professionalism, leadership, and heroism at places like Belleau Wood, Bataan, Normandy, the Chosin Reservoir, Khe Sanh, and Baghdad. When their country needed them, UConn ROTC graduates have been there to lead young American men and women in combat—and all too often, they’ve given their lives while doing so.

We here at Archives and Special Collections take pride in the knowledge that, in preserving the documents and artifacts related to UConn ROTC for future generations, we are playing a small part in safeguarding that legacy. If after reading these posts you are interested in donating artifacts or documents related to your own time in UConn ROTC to the collections, please contact Betsy Pittman, University Archivist, at betsy.pittman@uconn.edu.

Thank you for reading! And Happy 100th Birthday ROTC!

Sources

Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

Connecticut Daily Campus, 1970-1989

Nutmeg (University of Connecticut Yearbook), 1970-1995

University Archive Subject file, “ROTC”

University of Connecticut Photograph Collection:

Record Group 1, Series VI, Boxes 93-95

Record Group 1, Series II, Box 244

Record Group 1, Series XIV, Box 222

Misc.

Neiberg, Michael S. Making Citizen-Soldiers: ROTC and the Ideology of American Military Service. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Renner, Gerald. “Does ROTC Belong on UConn Campus? The Debate Is Boiling Over.” Hartford Courant, April 5, 1995.

Stave, Bruce M. Red Brick in the Land of Steady Habits: Creating the University of Connecticut, 1881-2006. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2006.

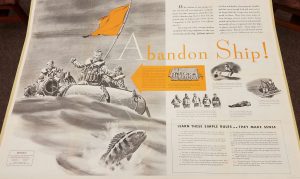

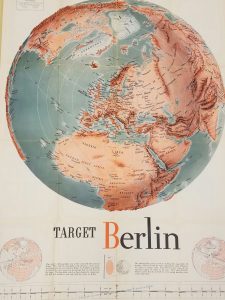

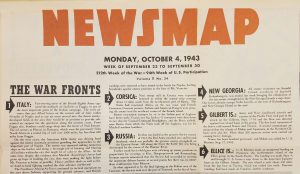

Just a few months after its transfer from the main library’s Federal Documents Collection, the World War Two Newsmap Collection is now available for patron use! The finding aid can be found here.

Just a few months after its transfer from the main library’s Federal Documents Collection, the World War Two Newsmap Collection is now available for patron use! The finding aid can be found here.