by Richard Telford

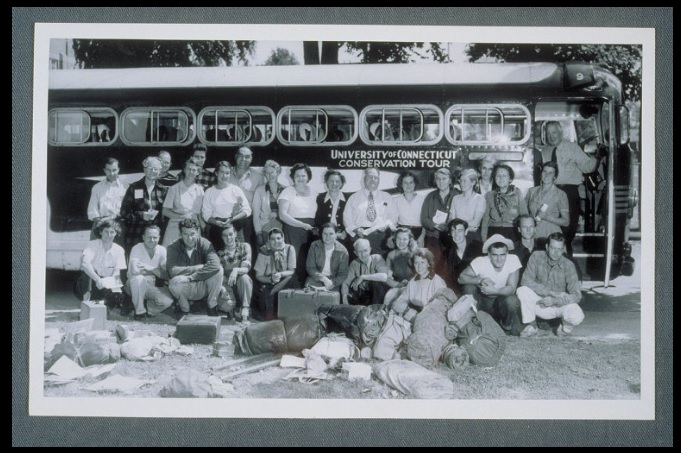

Author’s Note: Though the product of many hours of research, writing, and revision, this chapter is nevertheless a draft; it will be subject to revision as the larger book in which it will appear takes shape. This chapter follows the book’s prologue, posted last month. It is the fifth to be published on this site. The first three, published this past winter, were later chapters of the book, chronicling the Teales’ loss of their son David during wartime service in 1945. Those chapters can be accessed here. I welcome critical response to this work, either in the comment section below or through direct e-mail. I am grateful to the Archives and Special Collections staff for providing me the opportunity to share this work, and to the Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees for awarding me a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year. Contextual information about the project and manuscript can be found here.

Chapter 1: Chasing the Erratic Spotlight of Memory

Thinking of memory, it occurs to me what an erratic spotlight memory is, playing across the landscape of our past, picking out small areas, illuminating fragments of our experience. Out of a shrouded, shapeless limbo of forgotten things one experience suddenly comes to life.[i]

Edwin Way Teale, The Hampton Journal, November 15, 1961

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices? [ii]

Robert Hayden, from “Those Winter Sundays”

O sons of men,

You add the future to the future

But your sum is spoiled

By the grey cipher of death.

There is a Master

Who breathes upon armies,

Building a narrow and dark house for kings.[iii]

From The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night

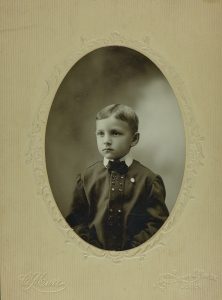

On June 2, 1899, Clara Louise Way Teale gave birth to a son, her only child, Edwin Alfred Teale. The preceding winter had unleashed the Great Arctic Outbreak of 1899. The Mississippi river had frozen solid from St. Louis to New Orleans, and Arthur T. Wayne, writing for the American Ornithological Society, documented the deaths by starvation and exposure to blizzard conditions of tens of thousands of birds: fox sparrows and juncos, woodcock and killdeer, pine warblers and meadowlarks.[iv] Across the globe, Danish schoolteacher Christian Mortensen introduced the first systematic method of bird-banding, offering a new window to life’s beautiful, abundant complexity.[v] Edwin himself would reflect upon these events seventy-five years later as he commenced reconstructing his earliest days to tell his life’s story.[vi] Endings juxtaposed with beginnings, death juxtaposed with life. Edwin Teale, too, entered a childhood defined by such seeming contradictions: confinement and freedom, loathing and admiration, hatred and love. The delivery, which took place in a modest Iowa Avenue frame house beside Hickory Creek in Joliet, Illinois, was “a hard [one] that almost took” Clara Teale’s life.[vii] Several days later, Clara contracted typhoid fever, from which she would not fully recover until September. While his mother recovered, and his father, Oliver Cromwell Teale, labored long hours as a skilled locomotive mechanic in the Michigan City Railroad roundhouse, Edwin was cared for by Oliver’s sister Annie Brummitt and her husband George. The Brummitts had recently lost their only child at birth. Many years later, Clara Teale reflected, “I don’t think any of us quite realized what it meant to them to give up that baby,” and how these earliest days of Edwin’s life filled that void, if only briefly.[viii]

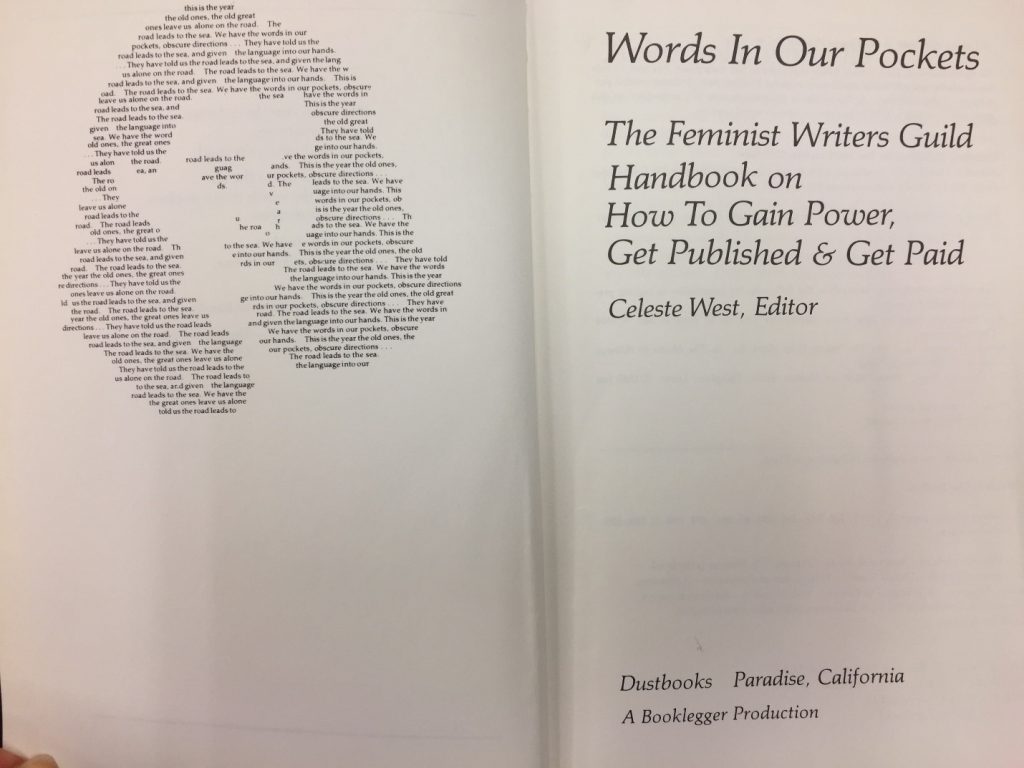

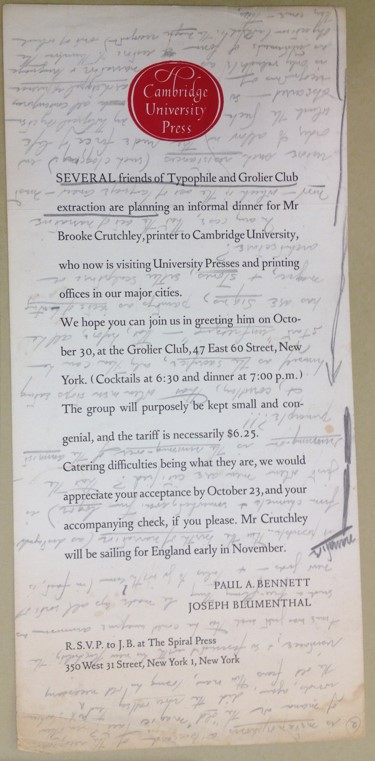

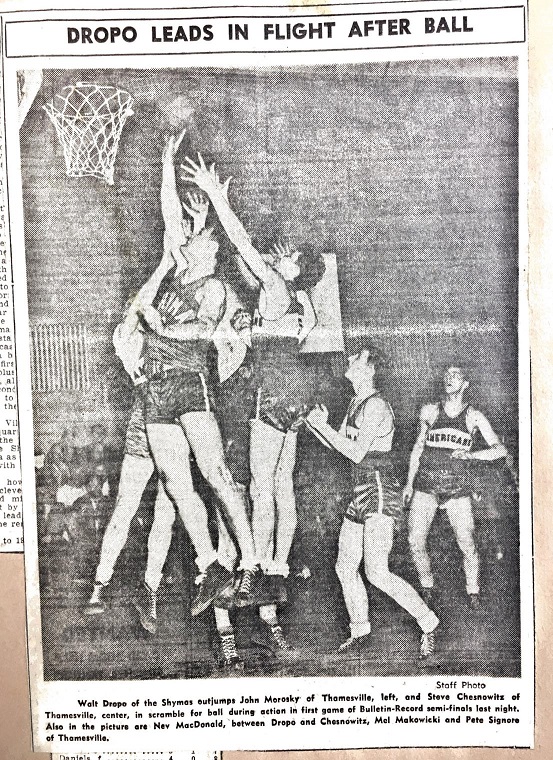

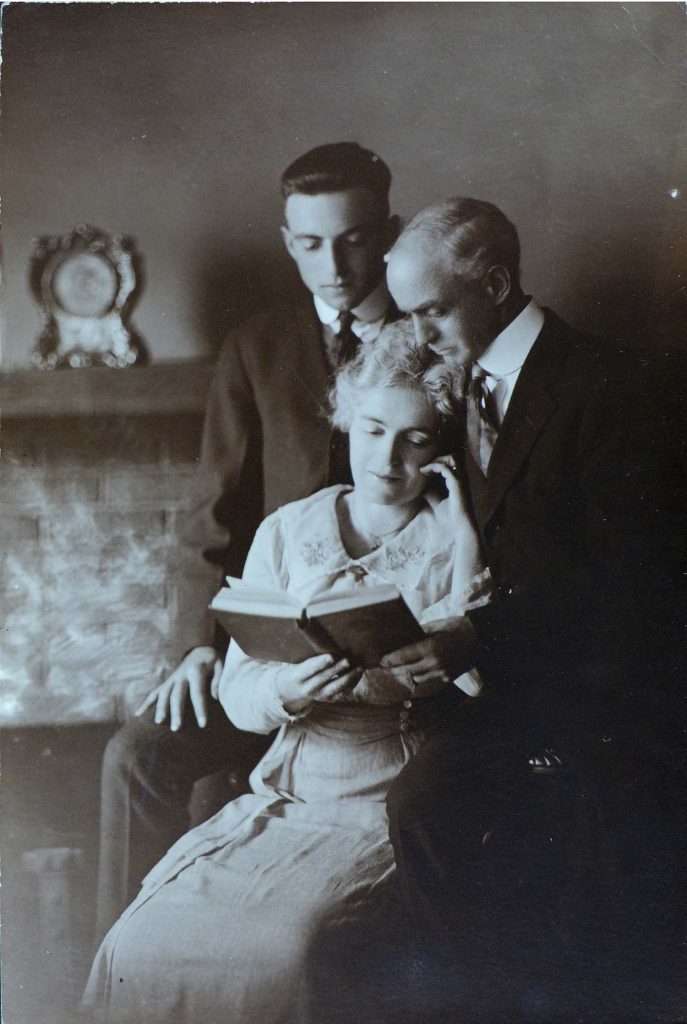

A studio portrait of Edwin Way Teale with his parents, Clara Louise Way Teale and Oliver Cromwell Teale, circa 1916-1918

Clara Teale recovered from typhoid in September of 1899, and she, Oliver, and four-month-old Edwin moved into a home that had been under construction on June 2. The East Washington Street home, just outside the Joliet city limits, “faced a wide expanse of wasteland,” hundreds of acres of “weed-covered hillocks and hollows” that “remained from the digging of gravel that had been deposited by the glaciers.”[ix] This scarred and desolate landscape later afforded Edwin a site for his earliest peregrinations in nature, and these offered a reprieve from his mother’s relentless dedication to her only child’s “improvement,” a dedication that left him, “much of the time, desperately unhappy.”[x] Amongst the overgrown hollows, he often unearthed “small cylinders of stone…the fossil remains of prehistoric crinoids,” which he at first mistook for “Indian beads.”[xi] Wandering in nature, even in a place that others saw as weed-choked and disfigured, Edwin felt “a sense of coming home” that eluded him elsewhere in Joliet.[xii]Later he would praise with equal feeling the aerial prowess of invasive European starling flocks “turning corners like soldiers on parade” and the “snow-white shimmer” of wheeling seaside flocks of delicate sanderlings.[xiii] Where others saw ugliness in nature, Edwin saw beauty and purpose, undiluted by arbitrary human judgments.

The interior of the East Washington Street home contrasted sharply with the wasteland framed by its windows. Its contents painted a portrait of Clara Teale as a cultured, thoughtful, and deliberate woman. An oil on canvas of Niagara Falls, painted by Clara and mounted in a wide gilt frame, adorned the parlor wall. Below it, against a corner of the room, leaned an alpenstock, the antecedent to the modern ice axe, trailing a ribbon of “narrow horizontal bands of brilliant colors.” Edwin would later recall that the alpenstock, among all other curiosities of the house, “especially fascinated me.”[xiv] Clara Teale’s decor likewise reflected the heightened popularity of nature study at the advent of the twentieth century. A small stand housed an ostrich egg, a peacock feather, and other natural specimens.[xv] Seashells “brought from Newport” adorned the room, including a large conch shell that served as a door stop. Putting the conch to his ear, young Edwin “could hear the sea.”[xvi]

There were also numerous pictures of sunsets scattered amongst the house’s contents, clipped from popular magazines by Oliver Teale. In his few spare moments of leisure, Edwin’s beleaguered father “wrote descriptions” of these scenes, his only foray into art in a draining, workaday life.[xvii] Edwin later attributed his own “passionate love of beautiful scenes” in part to his father’s early influence.[xviii] In 1942, fourteen years after Oliver’s death, Edwin would dedicate his sixth book, Byways to Adventure: A Guide to Nature Hobbies, to his father—a tacit acknowledgment that his father earned but never got the luxury of such pursuits. At the other end of the parlor, an upright piano, “the first thing purchased after the house was built,” occupied a wall of its own. What Edwin later remembered most of this piano was not his mother’s playing but “the successive generations of baby mice its interior harbored,” an apt preview of his future leanings.[xix] Despite its rich décor and the intellectual sensitivities it represented, Edwin’s childhood home was more a prison than a sanctuary, transmuting the barren wasteland of the gravel bank to a refuge, a place of retreat into nature and into himself.

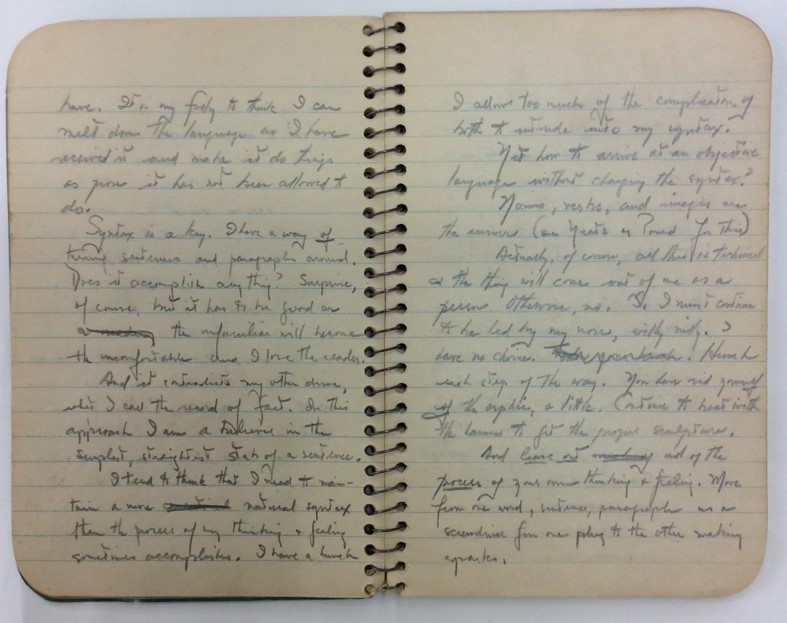

Edwin’s relationship with his mother was deeply complicated, and he struggled for the remainder of his life to reconcile its polar contradictions. In 1974, shortly after his 75th birthday, Edwin wrote a full chapter on the complexities of their relationship for The Long Way Home, the autobiography he would not complete. He titled the chapter “Memories of a Bent Twig,” alluding to Alexander Pope’s 1732 observation that “Tis education forms the common mind,/Just as the twig is bent the tree’s inclin’d.”[xx] The choice of this allusion reflected the profound influence of Clara’s unstinting efforts to render every experience of Edwin’s boyhood “a lesson, a training in character.” In Clara’s view, “Life was a preparation for some other end, not an end in itself.”[xxi] She thought only in the future tense. “When I was young,” Edwin reflected in 1974, “little was done just for the fun of it…it seems to me I was one of the most bent twigs the world has ever known.”[xxii] He struggled for the rest of his life to understand the choices his mother had made, to check his extraordinary bitterness about the “schizophrenic world”[xxiii] she created for him, and to render the experiences of his earliest years in honest, fair prose.

Prior to her marriage, Clara Way had been a school teacher in “various country schools near Furnessville, at Boone Grove and elsewhere in northern Indiana.”[xxiv] It was, for her, a period of great personal fulfillment, defined especially by the memory of a particular end-of-school picnic, “a memory that she cherished as long as she lived.”[xxv]

She and the children rode on a hayrack to the picnic site and the pupils had put a chair, decorated with flowers, in the middle of the wagon. She sat on it with the children grouped around her.…It symbolized her dream: to be surrounded by small children looking up to her for advice and counsel. For her great passion was molding the minds and characters of the young.[xxvi]

Here was the culmination of her efforts, and, as importantly to her, the adulation that could accompany such efforts.

By the fall of 1899, the East Washington Street home had become her classroom, Edwin her star and only pupil. “In this, her lifelong goal of bending tender twigs,” Edwin wrote, “she found I was the closest, the one around the most.”[xxvii] But Clara’s was a doomed effort crippled by self-absorption. Any adoration, any veneration that Edwin openly offered his mother, despite its sincerity, only veiled deep resentment that grew with time and came to define his recollections of her. But Clara could not, or would not, see this. She clung to the image of admiring children surrounding her on the hayrack. When Edwin was in high school, Clara arranged to have a studio portrait taken of the family. In it, Clara is seated at center, her right hand holding an open volume that she peruses. Oliver stands to her left, one hand steadying the book, as Edwin, standing directly behind his mother, looks on. Clara looks blissful, her son and husband rapt with admiration. The pastoral image, preserved for the annals of time, belies the turbulent waters that roiled beneath.

Clara Teale’s pedagogical methods haunted Edwin’s childhood. “In her desire to train me as I should be trained,” he wrote later, “my mother wanted to be with me every hour, to know what was going on in my mind and heart all the time. She wanted to be inside me. She wanted to have no secrets…she wanted me to be transparent glass that she could look through.”[xxviii] Once, returning home from grade school, Edwin found that his mother had left “a note on the kitchen table saying she would be away for two or three hours.” Later, however, he discovered her “sitting quietly in another room apparently waiting to see what I would say and do when I thought I was unobserved and alone.”[xxix] Later, when he befriended a girl he had met during a stay at Lone Oak, Clara steamed open the girl’s subsequent letters to Edwin for first inspection.[xxx] Such extremes, she argued, were necessary to make Edwin “the kind of person she wanted me to be,” a result that “meant more to her than anything else in the world.”[xxxi] But such measures served only to fog the transparent glass Clara sought. They rendered Edwin “slightly secretive, throwing up barriers beyond which people [could] not go.” Under his mother’s unrelenting gaze, Edwin found himself “continually retreating within myself to some secret room that should, for everyone[,] be inviolable.”[xxxii] Formed early, Edwin struggled in adulthood to shed the defenses of a childhood that “was largely an ordeal at a time when it should have been fun.”[xxxiii]

Though Edwin found his mother’s training painfully oppressive, he did not question her motives, at least not publicly. In his 1943 Dune Boy, he wrote of his parents as “sincere, hard-working, religious people,” offering only one muted complaint: “At home I was trained for Heaven rather than for the world as it is.”[xxxiv] In 1974, in the most revised draft of The Long Way Home, he wrote:

As I look back, nobody I have ever known ever tried harder to do what she thought was right than my mother. Nobody ever wanted more to help make the world a finer, better place for all. She was sincere. She was honest—so far as she understood her own motivations—in her striving to be a force for good in the world.[xxxv]

His assessment was extraordinarily tempered when viewed in light of his private notes. “Probably nobody ever born…understood less what made her[self] tick,” he noted privately. She was “an interesting case for a psychologist,” he added. “By fooling her mind [she] got so her mind fooled her.”[xxxvi] His understanding of her terribly skewed self-knowledge did little to mitigate his deeply-rooted anger. In undated autobiography notes, he considered titling a section of the book “Lies My Mother Told Me.” Below the notation, he enumerated a full page of these.[xxxvii] Elsewhere he reflected, “Not all people who do good deeds deserve credit for good motives.” This he followed with an assessment of his mother’s increased involvement in church work as Edwin grew older: “Do a good deed and get away from house-work and children by doing it!”[xxxviii] Clara’s chronic absence during Edwin’s adolescence hurt him deeply, especially because she had labored so intently in his early years to create in him an absolute dependence upon her.[xxxix] On New Year’s Day, 1911, six months shy of his twelfth birthday, Edwin enumerated a set of resolutions for the coming year, the first of which is especially heart-rending: “I hope that mama will stay home and I will do all that is in my power to help and please her.”[xl] He had just spent the Christmas holiday at Lone Oak, about which he had noted two days earlier, “This is the greatest vacation I ever had.”[xli] He was sorry to leave Lone Oak, he added below his list of resolutions, but “I am glad to come to mamma if sheel only stay home.”[xlii] But Clara would not stay home, driven less by her desire to escape domesticity and more by “the limelight” church work afforded her, “the sense of being somebody,” the affirmation that accompanied highly public righteous acts.[xliii]

Elsewhere, Edwin lamented the times his mother “cried because I used a more pleasant tone of voice to the telephone operator’” than to her. “Neurotic atmosphere—” he added, “wonder not breakdown or suicide.” Of this latter wonder, he did not specify Clara or himself.[xliv] Of her wedding vow to be faithful unto death,” Edwin questioned, “Faithful to whom?” and answered succinctly: “Herself.”[xlv] Still, he was reticent to share with his reading public the full depth of his bitterness. In a paragraph later struck from the most complete autobiography draft, he wrote:

I am well aware of the awesome power that lies in the hand of anyone writing of his own life, the power to emphasize one aspect, to tip the scales in favor of himself, to color events almost unconsciously. The writer can state his story; the one written about cannot correct the impression. So I hope the reader will give every benefit of the doubt to my mother in reading this chapter of my recollections for my first years.[xlvi]

While Edwin later cut this qualification, he nonetheless exercised great restraint in wielding his power to shape the reader’s view of his mother. In the last revision completed before The Long Way Home was put aside in the fall of 1974, Edwin offered the following view of Clara:

My mother not only read to me, she encouraged me to try to write and she taught me that ever-valuable lesson—to get up and try again when I failed. She appreciated wildflowers and, as I noted in the dedication of my first nature book, Grassroot Jungles, saw beauty in humble things. I loved my mother. There was no one I revered more. I recognized she was completely dedicated to my improvement.[xlvii]

It is impossible to know how much the decision to include this praise was born of obligation and how much from authentic feeling. Its substance was certainly true. Still, even in the public venue of autobiography, Edwin could not leave it unqualified. It was his “difficult aim,” he told the reader, “to tell as exactly as I can what life has been like for me.” And so, to the passage above, he added, “And yet—all I know is that as a child I was, much of the time, desperately unhappy.”[xlviii]

* * * * * *

If Clara Teale was the righteous and dominant force of the home with whom to reckon, her husband, Oliver Cromwell Teale, was her foil. A soft-spoken, kind-hearted man of integrity, Oliver spent few waking hours in the home he shared with his wife and only child. Employed as a skilled locomotive mechanic in the Michigan Central Railroad roundhouse, he worked twelve-hour shifts, six days per week, to bring home weekly pay of fifteen dollars. In winter, he departed for work in the dark and returned thus. “In my memories of him,” Edwin wrote of his father, “he always seemed tired. There was little play in him. But it must be remembered that I saw him mainly in the evenings at the end of a long day’s work.”[xlix] At fourteen, living in his native Yorkshire, England, Oliver began work in a textile mill, and his life thereafter would be that of the laborer. As a young man, he emigrated to the United States with his younger brother, Haigh, and his older brother, William.[l] Several years later, their parents, Jeptha and Ellen Teale, followed, settling on a modest farm at the edge of the Indiana dunes—a farm adjacent to that of Edwin and Jemimah Way. There, Oliver met Clara Louise Way, his future bride. Ellen Teale died in 1895, four years before Edwin’s birth. Of Jeptha, Edwin had “but the vaguest memory of him, a sturdy upright man with an immaculate white beard which he washed with soap and water every morning.”[li] In 1901, Jeptha, now a widower, sold the 19-acre fruit farm and moved into the home of George and Annie Brummit. He died in January of 1904, six months shy of Edwin’s fifth birthday.[lii]

Oliver had grown up one of ten children, and his early life in Yorkshire had been defined by scarcity. As an adult, he stood at five feet, seven inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, his slight build making him ideally suited to enter the bellies of steam locomotives to hammer-test their iron flues. He was five inches shorter than Edwin by the time the latter graduated high school. “It may well be,” Edwin wrote later, “that he would have been taller if he had had ample food in childhood.”[liii] As a father, Oliver “retained the orderly habits of his boyhood” and remained governed by the schooling of early poverty. “My father mended his own shoes,” Edwin recalled later, “and my mother cut his hair.”[liv] During Edwin’s boyhood, the family was “never in need”—they owned their home and carried no debt—but, he qualified, “We were always on thin ice. There was rarely a surplus. Living close to the edge of the precipice you must walk carefully lest a pebble roll under your feet.”[lv] Oliver labored Monday through Saturday. On Saturday night he polished the family’s shoes for Sunday church. “On Sundays,” Edwin wrote, “he was urged on by that most popular of songs at the Methodist church we attended: ‘Work for the night is coming, when man works no more.’”[lvi] On Monday the cycle began again, and one is reminded of Robert Hayden’s oft-anthologized poem “Those Winter Sundays,” which begins:

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

It was the common pattern for the laboring family man of the early twentieth century. A long day’s labor provided sustenance and stability but little more. For the Teales, there were few luxuries.

Decades later, Edwin reflected thoughtfully, and perhaps a little ruefully, on the trajectory of his father’s life:

Looking back over the span of years, I recognize that my father was a man who lived a life without surpluses—without a surplus of energy, without a surplus of money, without a surplus of time. He never got enough—soon enough…He was not the kind for whom scrolls are inscribed and public dinners held…He was quiet and hard-working. He was well-liked and respected. He could be depended upon…The life he led did not embitter him. It did not break his spirit. Life did not overwhelm or conquer or crush him. Life tired him out.[lvii]

Despite the genuine praise of the passage above, Oliver did not escape the bitterness of Edwin’s private reflections on the unhappiness of his childhood. “My father was dependable, old reliable—faithful Oliver,” Edwin wrote in undated autobiography notes.[lviii] He elaborated no more, but the duality of his meaning, taken in the context of other notes, is clear. Edwin appreciated deeply his father’s steadfast, uncomplaining fulfillment of his duties—an authentic act of love that robbed him of his health and led him, at fifty-two, to a grave fittingly inscribed, “Faithful Unto Death.”[lix] Still, he was embittered just as deeply by his father’s malleability when confronted with his domineering wife’s will as she “turned the screws of psychology” on the two of them.[lx] Oliver was an “inarticulate father,” Edwin complained elsewhere, “always subordinate,” manipulated by Clara to believe he had won a “great prize” in marriage.[lxi] He was “sensitive—but he could not express his emotions” while “others seemed more” able to do so.[lxii] Exhausted by back-breaking labor and Clara’s relentless pursuit of “her great thrill [of] ‘moulding’ others,” Oliver Teale “left the job of bending the twig” to Clara, and by doing so left Edwin disillusioned and resentful.[lxiii]

Vivid amongst the scattering of Edwin’s early memories of his father were a handful of visits to the Michigan City roundhouse. At these times, Oliver lifted “the veil of that mysterious world into which he disappeared” each day. For a young boy, such visits were magical, and for Edwin, many years later, they “merged into one dreamlike memory.”[lxiv]

I remember when I was five or six or so and climbing with him to the engineer’s seat in the cab of a huge freight engine. Slowly he eased back a lever. With a long hiss of steam, the locomotive moved ponderously forward until we were swallowed up in the cavernous gloom of the roundhouse. There I was greeted with strange smells—the odor of hot oil and metal and steam—unfamiliar sounds—the clang and reverberation of pounded metal—new sights—men moving about among the dim shapes of towering locomotives lighting their way with smoking flares formed of burning oil-soaked waste. I watched my father, carrying his flare, squeeze his way through a firebox door to inspect the boiler of one engine and heard the ring of his hammer as he tested the flues.[lxv]

In these ephemeral hours, his father “seemed like some knight on a charger, a romantic figure.”[lxvi] Later, Edwin found the composite memory of these visits “strange [and] haunting.”[lxvii] The ringing of his father’s hammer was the tolling of a bell for a life absent luxury, a life foreshortened by little-noticed sacrifice. It heralded the coming night when the man, the father, would work no more. It was the peal of love’s labors, of the “austere and lonely offices” for which thanks were neither sought nor expected, and rarely gotten.

* * * * * *

As an industrial center with “railroads converging from all directions,” Joliet, Illinois was likewise “a tramp center” at a time when thousands of itinerant men rode the rails hunting work or escape, driven from town to town by local sheriffs and railroad bulls.[lxviii] Less than a mile east of the Teales’ home, in an undeveloped tract named Davidson’s Woods, there was “an extensive hobo jungle…” where “wanderers cooked their food over little campfires and heated their coffee in tin cans.”[lxix] Clara Teale, despite her rigidness in the running of her own home, felt great empathy for the cavalcade of road-worn men who passed through Joliet. Such solicitude for the unwanted likely drew the ire of some neighbors. Such acts cast little limelight. Still, when these men appeared “from time to time…at our back door asking for a bite to eat,” Clara fed them without hesitation.[lxx] Edwin wrote of these unremembered acts of kindness in the last revision of his autobiography, perhaps to further soften his already-muted critique of his mother’s twig-bending efforts: “Times were hard, and my mother was kind-hearted and our house no doubt was widely known as an oasis for tramps in their travels.” He even quipped, “We began to notice cabalistic markings in chalk on the cement wall in front of the house…probably notices to other tramps that easy pickings lay within.”[lxxi]

Despite his lighthearted autobiography treatment of the hobos who plied his mother’s kindness, an incident involving one of these nameless men haunted Edwin’s memory. In undated notes, he recalled a tramp lying on a stretcher beside the tracks of the Eligin, Joliet, and Eastern railway, his severed leg beside him. It was one of many tragedies Edwin witnessed firsthand in his early years. Later, as he compiled voluminous notes for his autobiography over a thirty-year period, the erratic spotlight of his memory returned with striking frequency to these tragic events. Year after year, he enumerated these events on redundant lists, sometimes adding a newly-recalled detail or event. The earliest of these, his “first glimpse of the terror that lies just beneath the bright surface of life,”[lxxii] was the death in winter of a cart-horse that slipped on ice directly in front of the Teales’ East Washington Street home:

I saw my father disappear out the front door. I saw my mother following with an armload of blankets. I had no idea what had occurred. Peeking under the drawn curtain at the parlor window, I saw dark figures huddled around the prostrate animal. Lanterns threw shifting shadows over the scene…Then I heard the crack of a rifle…In the morning the horse was gone but a large red pool of blood had frozen on the ice.[lxxiii]

The scene remained “alive[,] buried in the far recesses of my mind,” he wrote nearly seventy years later.[lxxiv]

In stacks of undated autobiography notes, Edwin documented event after event that, as he reflected later, illustrated “how often death has swept close to me.”[lxxv] Once, for example, while he stood at the edge of a water-filled quarry, a favored swimming hole, a boy beside him dove in headfirst, struck a submerged rock, and died from a broken back.[lxxvi] Then there was Cube Brooks, a playmate of Lone Oak summers, who was kicked in the head by a horse and died from the blow.[lxxvii] Another time, swimming in Lake Michigan on the Indiana dunes side, Edwin watched as a drowned girl was pulled from the water. Decades later he recalled clearly the strands of hair that hung flaccid down her waxen face.[lxxviii] Later, working a summer job at the Starr Lumberyard while attending Earlham College, he watched in horror as a deaf co-worker, “unable to hear the warning bell of a backing switch engine, was run over and killed hardly more than a hundred feet from where several of us stood helpless.”[lxxix] On two occasions, Edwin rode trains that collided with automobiles at crossings, killing their occupants.[lxxx] These experiences and others made Edwin feel as though “lightning was striking all around” him.[lxxxi] They left him deeply fearful, often “treading softly, seeking the shadows, trying to avoid attracting the attention of some malign fate I could not name.”[lxxxii] He became acutely aware of the tenuous and unforgiving universe we inhabit, and that awareness haunted him for the rest of his life. “I seemed skating over a deep, dark stream,” he wrote later. “The ice held but I could never forget for long the water that flowed below.”[lxxxiii] Life’s triumphs and joys seemed always to unfurl in the shadow of approaching disaster.

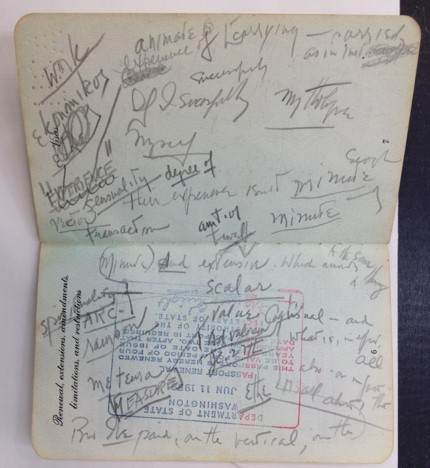

While these tragedies haunted Edwin, the “sense of uncertainty” they fostered likewise heightened his “intense delight…in the beauty of the passing minute.”[lxxxiv] It was analogous, he wrote later, to the way in which “some landscapes take on a magical atmosphere when touched briefly by sunshine while black clouds are piling up in the sky behind them.”[lxxxv] In life’s frailty, beauty resided, in its impermanence, meaning that transcended time. To his lists of “black cloud” events, Edwin often added the title “The Gray Cipher.” In doing so, he alluded to a short poem from “The Extraordinary City of Brass,” a story from The Thousand Nights and the One Night, more commonly known in the English-speaking world as The Arabian Nights. In the story, a traveling party enters the ruins of a great city, now “buried in silence as in a tomb.”[lxxxvi] An inscription on a battlement warns the travelers that “the grey cipher of death” is always near, “building a narrow and dark house for kings” and commoners alike, waiting to spoil the sum of our imagined futures.[lxxxvii] Edwin titled the final chapter of his autobiography “The Gray Cipher.” In it, he wrote only one sentence, stating his intent to offer “reflections of various kinds, especially on life and death….,”[lxxxviii] but his sum, too, was spoiled, the pages left unfilled, a reminder of the dark, narrow house that awaited him and awaits us all.

Richard Telford has taught literature and composition at The Woodstock Academy since 1997. In 2011, he helped found the Edwin Way Teale Artists in Residence at Trail Wood program, which he now directs. He was a long-time contributing writer for The Ecotone Exchange. He was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant by the University of Connecticut to support his work on a book about naturalist, writer, and photographer Edwin Way Teale. The Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees likewise granted him a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year to support this work.

References:

Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, The, Volume 2, Translated from the French translation of Dr. J.C. Mardrus by Powys Mathers, New York & London: Routledge, 2005, Taylor and Francis e-Library ed.

Hayden, Robert. “Those Winter Sundays.” Collected Poems. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Pendley, Trent D. “Jeptha Teale.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=6504158. Accessed 31 May 2017.

Pendley, Trent D. “Oliver Cromwell Teale.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi- bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=6504214. Accessed 27 June 2017.

Pople, Alexander. The Works of Alexander Pope Esq. Volume III: Containing his Moral Essays. London: J. and P. Knapton in Ludgate Street, 1752.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay” chapter notes, drafts, 1974. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2167, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Days Without Time: Adventures of a Naturalist. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1948.

Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957.

Teale, Edwin Way. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [1910]. Box 85, folder 2664, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. EWT’s early letters to parents, 1909-1912. Box 142, folder 2880, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2169, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2168, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Notes, Clippings, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2163, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “The Gray Cipher” Chapter Skeleton. 20 Sept., 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. The Hampton Journal, 1959-1961, unpublished journal. Box 120, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Woodland Days” chapter notes, research, drafts of manuscript, correspondence, 1974 August 19. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2170, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Wayne, Arthur T. “Destruction of Birds by the Great Cold Wave of February 13 and 14, 1899.” The Auk, 16: 2 (Apr 1899), 197-8.

Wood, Harold B. “The History of Bird Banding.” The Auk, 62: 2 (Apr 1945), 256-265.

Notes:

[i] Teale, Edwin Way. The Hampton Journal, 1959-1961. 15 November, 1961.

[ii] Hayden, Robert. “Those Winter Sundays.” Collected Poems. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 41

[iii] The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Volume 2, 298.

[iv] Wayne, Arthur T. “Destruction of Birds by the Great Cold Wave of February 13 and 14, 1899.” 197-8.

[v] Wood, Harold B. “The History of Bird Banding.” 259

[vi] Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 1

[vii] Ibid. 2

[viii] Teale, Clara Louise. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[ix] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 1

[x] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 6

[xi] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 1

[xii] Teale, Edwin Way. Notes, 7 August 1974. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Days Without Time. 20, 238.

[xiv] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 4

[xv] Ibid. 4

[xvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 8

[xix] Ibid. 4

[xx] Pople, Alexander. The Works of Alexander Pope Esq. Volume III: Containing his Moral Essays. 192

[xxi] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 2

[xxii] Ibid. 2, 1

[xxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 1

[xxv] Ibid. 1

[xxvi] Ibid. 2

[xxvii] Ibid. 2

[xxviii] Ibid. 2

[xxix] Ibid. 3

[xxx] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 3

[xxxii] Ibid. 3

[xxxiii] Ibid. 3

[xxxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957. 5.

[xxxv] Ibid. 2

[xxxvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 6

[xl] Teale, Edwin Way. Entry, 1 Jan. 1911. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [1910]. Box 85, folder 2664.

[xli] Teale, Edwin Way. Entry, 30 Dec. 1910. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [1910]. Box 85, folder 2664.

[xlii] Teale, Edwin Way. Entry, 1 Jan. 1911. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [1910]. Box 85, folder 2664.

[xliii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xliv] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xlvii] Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig,” draft, 3-7 Aug., 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 6

[xlviii] Ibid.

[xlix] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 8

[l] Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 3

[li] Ibid. 4

[lii] Pendley, Trent D. “Jeptha Teale.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=6504158.

[liii] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 7

[liv] Ibid. 6

[lv] Ibid. 6

[lvi] Ibid. 7

[lvii] Ibid. 9

[lviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[lix] Pendley, Trent D. “Oliver Cromwell Teale.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=6504214.

[lx] Teale, Edwin. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 9

[lxv] Ibid. 9

[lxvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[lxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 9

[lxviii] Ibid. 3

[lxix] Ibid. 3

[lxx] Ibid. 3

[lxxi] Ibid. 3

[lxxii] Ibid. 5

[lxxiii] Ibid. 5

[lxxiv] Ibid. 5

[lxxv] Ibid. 5

[lxxvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[lxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. Box 63, folder 2163.

[lxxix] Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home,” draft, 28-31 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 5-6

[lxxx] Ibid. 5

[lxxxi] Ibid. 6

[lxxxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[lxxxiii] Ibid. 6

[lxxxiv] Ibid. 6

[lxxxv] Ibid. 6

[lxxxvi] The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, Volume 2, 298.

[lxxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxxviii] Teale, Edwin Way. “The Gray Cipher,” skeleton chapter, 20 Sept. 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187.