By Richard Telford

Author’s Note: Though the product of many hours of research, writing, and revision, this chapter is nevertheless a draft; it will be subject to revision as the larger book in which it will appear takes shape. The chapter published below, “Losing the Remembrance of Former Things,” follows two preceding chapters, published in January and February on this site: “The Lonely Suffering of the Fallible Heart,” which can be viewed here, and “Throwing Bricks at the Temple,” which can be viewed here. For greatest clarity, these chapters should be read in order. This present chapter is being published on the 72nd anniversary of the combat death of David Allen Teale near the end of World War II. David figures prominently in this and the preceding chapters. The timing of this publication is an apt reminder of the oft-forgotten sacrifices of previous wars. I welcome critical response, either in the comment section below or through direct e-mail. I am grateful to the Archives and Special Collections staff for providing me the opportunity to share this work, and to the Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees for awarding me a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year so that this work could be undertaken. Contextual information about the project and manuscript can be found here.

Chapter 11: Losing the Remembrance of Former Things

Is there a thing of which is said,

“See, this is new”?

It has been already,

In the ages before us.

There is no remembrance of former things,

Nor will there be any remembrance

Of later things yet to happen

Among those who come after.[i]

Ecclesiastes 1: 9-13

Of course, there are at present, and no doubt will continue to be for many generations yet, a number of fire-eating war-mongers and dashing blades who will always bounce about the delights of battle and the salubrious qualities of slaughter. But these, when genuine, are atavisms, and must gradually become as extinct as dodoes, as the world advances in sense and experience…[T]he New Army…has seen and felt a very great deal too much of the reality of war to be under any illusion as to its loveliness or enjoyability. Unredeemed horror is the whole thing, a horror that breaks up the soul of man into a gibbering wreckage.[ii]

Reginald Farrer, The Void of War: Letters from Three Fronts, 1918

To be killed in war is an event beyond our yes and no. It is a great sorrow but not a tragedy. The collapse of character alone is tragedy; not the events that test it from without. A single day of life with courage and character towers above the years of a centenarian if lived as a plaything of fate.[iii]

Edwin Way Teale, January 3, 1945

On the back side of the Norman Rockwell April Fool cover of The Saturday Evening Post that Edwin sent to David on Easter Sunday of 1945 is a full-page advertisement for the Parker “51” Aeromatic fountain pen. A strong, sure hand, its palm towards the viewer, holds the pen delicately between extended thumb and middle finger. The index finger steadies it from behind, the nib pointed upward. The hand is positioned just as the ad’s viewer might position his or her own, not just to inspect “this ‘most wanted’ pen in the world” but to appreciate the faux sapphire appointments on its engraved golden cap, to examine the understated black barrel with concealed nib, to feel the heft in hand. In the text below, The Parker Pen Company of Janesville, Wisconsin reminds the viewer that its production of “rocket fuzes and other war materièl” has stopped pen production. However, with the war’s end near, the ad continues, “More Parker ‘51s’ are on the way.” The ad’s large script headline, bisected by the pen and hand, assures the reader, “Sooner than you think…a Parker ‘51’ may be yours.”[iv]

In two letters sent in the fall of 1944, one from England to his mother on November 1[v] and the other from France to his father on November 16,[vi] David Teale asked his parents to buy him a Parker “51” fountain pen. “If [the] cost is too great for your purse,” he wrote Edwin, “take the required amount from my nest egg.”[vii] On June 18, 1945, however, the Teales realized it was a purchase they would never make, at least not on David’s behalf. On that day, when Edwin Stroh’s father had called to report that the War Department had declared his son killed in action, the Teales lost all hope that David would return to them. Nearly two months later, on August 8, Edwin would write, “It was that afternoon in June that the bottom collapsed and let us drop into darkness. It could have happened. We saw finally it must have happened to David.”[viii] That day of cascading hopes brought “a violent thunderstorm in late afternoon,” and Edwin continued “working in a daze on another chapter.”[ix] The writing was torturous, but it was necessary torture, an act of survival, just as it had been in the preceding months. It was more so now. “Will I ever be able to finish it or go on?” he questioned. “Every line seems the last I can possibly write.”[x] Nonetheless, he persevered, and in the coming days he would work to exhaustion to keep The Lost Woods on schedule, not in spite of David’s fate but in answer to it. “It is worth-while work, work I would want to do up to my final hour,” Edwin continued on June 18. “I hope I can meet this worst blow life can give with my head up without cringing or giving in. I think I can; but it is the weeks and months and years beyond I dread. How wonderful our whole family is and has always been, so close together.”[xi]

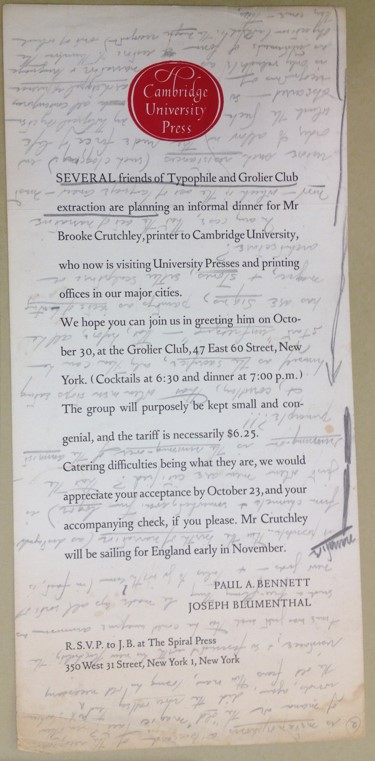

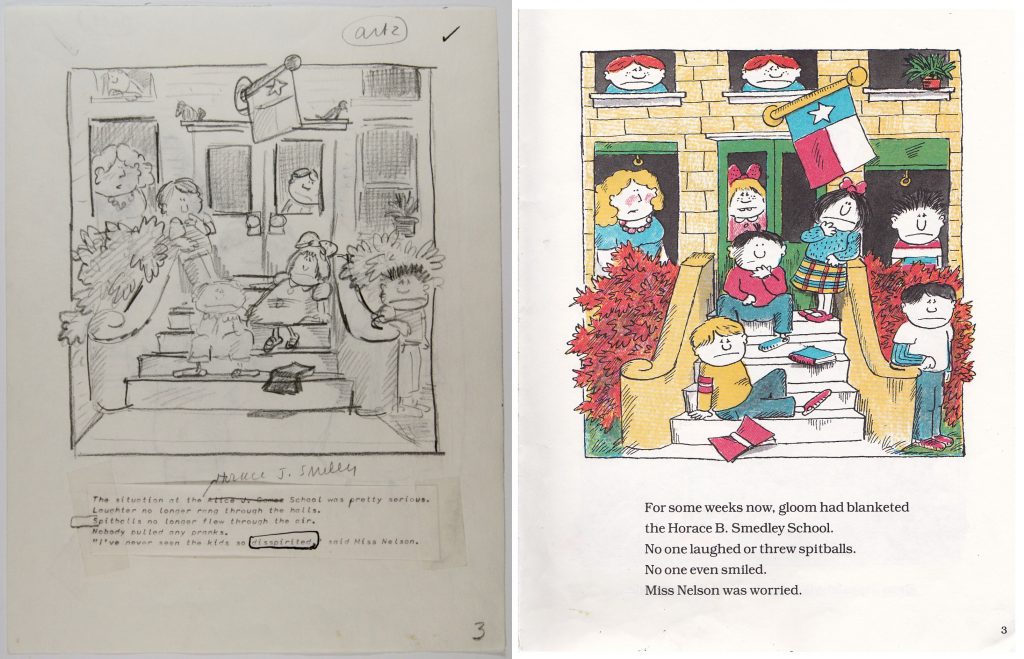

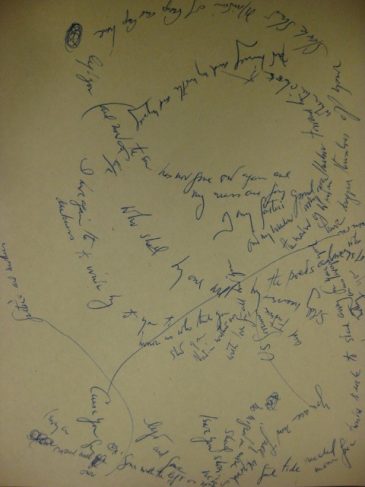

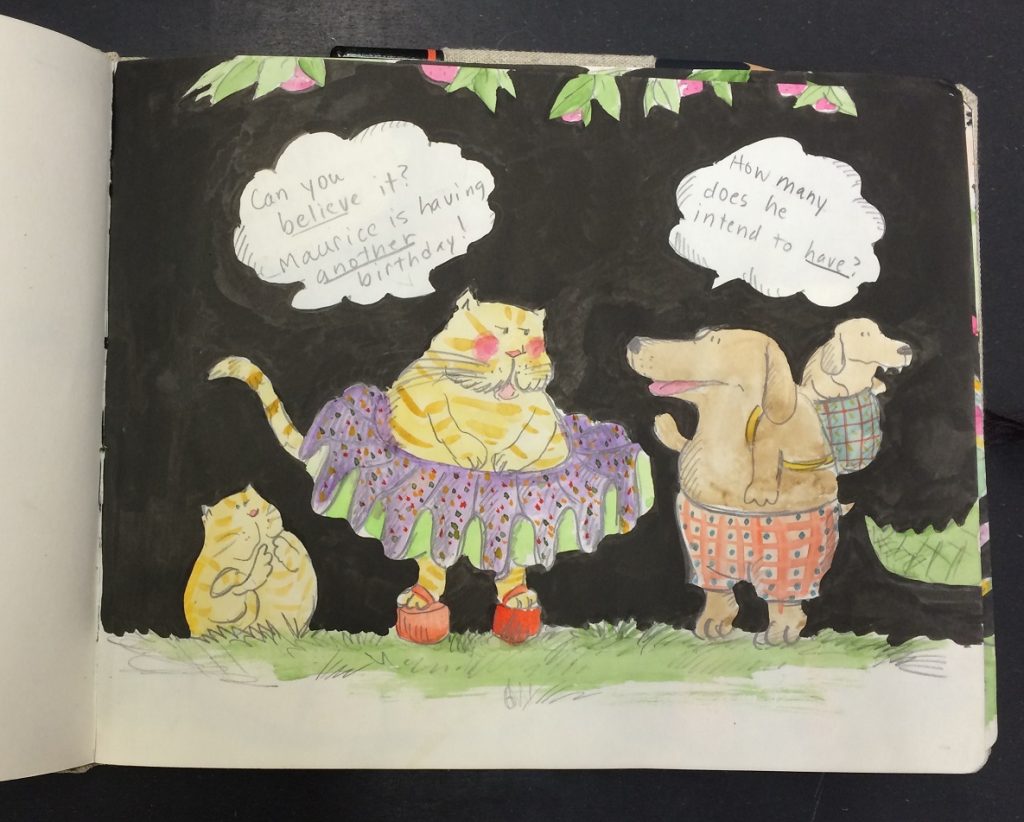

A partial view of a Nazi flag recovered by David Teale in Stadtkyll, Germany in early March of 1945. Seventeen members of a Tiger Patrol of the 346th regiment, 87th Division of the U.S. Army signed the flag. Five of the men whose signatures are visible here died on March 16, 1945, while crossing the Moselle River in Germany on a night reconnaissance patrol: Antonio J. Alvear, Bill Cummins, Eugene B. Pings, Edwin A. Stroh, and David A. Teale. Harold F. Gould Jr., whose signature also appears in this part of the flag, survived the mission. He wrote to Edwin Teale upon his return to the United States, sharing what he knew of the events of that night.

Two days later, on June 20, another of the packages they had sent David was returned, and their response to it, which Edwin recorded in the Guild diary, illustrates his and Nellie’s complete loss of hope: “A package comes back—This one marked ‘missing’ by Lt. Hawkins. But that means nothing. Our despair is complete.”[xii] Now, they simply waited for the inevitable. On that same day, the Teales received a letter from Walter F. Gould, the grandfather of Harold F. Gould Jr., explaining that his grandson was coming home on furlough from Europe before shipping out for the Pacific, and it might be possible for the Teales to see him or at least speak by telephone. Walter Gould could fully understand the Teales’ suffering. He informed Edwin both by telephone and letter that he had “had one son (31 years old, single) killed in that heavy drive in Belgium” the day after Christmas of 1944, roughly a week after David had witnessed and survived the pummeling of his regiment by German 88s. “I don’t think we will ever get over it,” the elder Gould told Edwin.[xiii] Just as the Teales were doing now, Walter Gould had reached out to a fellow soldier in his deceased son’s unit to understand more fully the circumstances of his death. In reply, he had gotten “a very nice answer telling one a good deal more about his death than the Army had told me.”[xiv] Though David’s fate now seemed certain, Edwin and Nellie, too, wanted to understand the events that had led to David’s death, events on which the younger Gould could, and later would, shed light.

A week after receiving Walter Gould’s letter, there was still no word from his grandson. The implications of Edwin Stroh’s confirmed death weighed heavily upon the Teales. Edwin noted, “Nellie and I plan to spend 2 weeks at Concord for our vacation in September.”[xv] There is no inclusion of the possibility that David might join them if he returned, for they now knew that he would not. One year earlier, on July 18, 1944, Edwin had written to David during a vacation with Nellie at Crocker Lake in Maine while David was at Fort Jackson: “We will have a good time for you at the camp. I hope another year, you can be along…if you aren’t walking down the coast!”[xvi] He referenced this walk down the coast a second time in a letter sent eleven days later: “When you take your long walk all by yourself, after the war, you ought to read John Muir’s ‘A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf.’ It is very good and would be right up your alley.”[xvii] But for David, there would not be “another year,” and Muir’s book would go unread. One year later, as the Teales planned their September Concord trip, they knew that David would not join them, and the timing of their departure from Baldwin was deliberate. On September 8, 1945, David would have turned twenty. Where better to find solace and shelter from their grief on that day than in Thoreau’s country. The following night, Edwin began reading Van Wyck Brooks’ The Flowering of New England, which had won the Pulitzer the year Edwin published Grassroot Jungles —“at least the chapter on Thoreau at Walden,”[xviii] Edwin qualified.

On June 28, Edwin once again found his footing, if tenuously, in his work on The Lost Woods. “On this evening,” he wrote, “I print ‘The Lost Woods’ on the top of the final manuscript box and stamp…my home address at top and bottom. This regular rite—engaged in since ‘Grassroot Jungles’ days—makes me feel a little nearer the completion of my long labors.”[xix] Such small, symbolic acts mattered. Each was an act of control, even as his life with David and their life as a family, “always…so close together,”[xx] had been rended by a complex, fickle chain of events over which he could have no influence. “In spite of everything,” he would later write, “there is nothing in the world I would rather be doing than working on my book. That, with all its complexities and pains, is the thing I want most to do.”[xxi]

In the days that followed, Edwin worked steadily in The Lost Woods, besieged by reminders of David’s absence. “So much to do!” he declared.[xxii] On Sunday, June 24, he taught the last Victors Sunday School class of the year, having a “fine talk” with two brothers, Warren and Edgar Fong. “So ends the Victors year,” he wrote that evening, “the last year when Davy was linked to it. Twelve years I’ve had the class. Can I keep on if David is gone?”[xxiii] On the following day, Mrs. Selby, a neighbor, brought Lieutenant Henry Loud to see the Teales, ostensibly to give them some insight on what might have happened to David, but, Edwin noted, he had “little to tell us of help on David. Depressed.”[xxiv] Two days later, on June 27, Forrest Dayton paid a visit to the Teales. Forrest, in Edwin’s estimation “David’s closest friend,” had likewise been deployed to Europe. Now, Forrest had returned, and David had not. It was a hard visit. “Headache lays me low in afternoon,” Edwin noted. In a postscript in the Guild diary, he added, “Twenty-eighth Chapter Done! Only Two to Go!”[xxv] One of these chapters was “The Calm of the Stars,” which could now serve only to memorialize David.

By July 1, the revised deadline for completion of the full draft of The Lost Woods, Edwin had only “The Calm of the Stars” left to complete. He spent the morning working on it but got “only two pages done,”[xxvi] using the rest of the day to review the completed chapters and rearrange their final order. It was not the day he had hoped for. The following morning, he began working at 7:30 a.m. and continued “until 8:52 p.m., with only time out for meals and a ½ hour sunbath.” With this last dash, as he often put it, he “completed the final difficult chapter on ‘The Calm of the Stars.’” He added: “Book completed, ready for revision, one day beyond my schedule—Thankful.”[xxvii] His celebration was understandably muted. Absent in his Guild diary entry are the flourishes with which he typically marked the completion of a book, even in its rough draft form. There are no headlines written in oversized characters; no ornate stacks of underlining elevate particular words; no geometric shapes adorn the margins; his daily progress note at the bottom of the page is formatted no differently than those of the preceding weeks. Instead, he noted in the sentences that followed: “Saddened by paragraphs in this chapter on Davy at Weller Pond. How impossible to believe he may never go on that trip again—never.”[xxviii]

The following day, Edwin took the 10:19 train into the city to visit Popular Science Monthly for a “reunion with the old crowd. Lunch with Richards, Samuels and de Santas. How thankful I have escaped the cells of 353 Fourth Ave!”[xxix] The juxtaposition of this reunion with the completion of the full draft of The Lost Woods is telling. While the “reunion” was certainly planned in advance, so too was the completion of the book draft, and Edwin had missed his target by only one day. Through this visit, he placed the celebration of one of the many fruits of the recent “glorious years in the sunshine”[xxx] alongside memories of the excruciating drudgery of Popular Science Monthly—now a painful phantom. The latter he had compared to “slavery” at a “Concentration Camp” two months earlier.[xxxi] This comparison, which now seems self-absorbed and indifferent to the horrific suffering endured in the camps of the Third Reich, must be considered in the context of the time, during which the ordinary American citizen was ill-informed on the events of Hitler’s war on the Jews, Roma, and other minority groups in Europe. Long-time New York Times journalist Max Frankel noted in 2001, on the 150th anniversary of the paper, that the events of what would only afterward be named the Holocaust “were mostly buried inside [the paper’s] gray and stolid pages, never featured, analyzed or rendered truly comprehensible.” There was, he concluded, no greater journalistic failure “than the staggering, staining failure of The New York Times to depict Hitler’s methodical extermination of the Jews of Europe as a horror beyond all other horrors in World War II,” and the Times’ coverage influenced that of many other journalistic organizations in New York and beyond.[xxxii] On this early day in July, Edwin’s view of the war was trained inward, as it had been two months earlier. The loss of David overshadowed all else, and this reunion with former Popular Science Monthly colleagues offered a spot of sunshine amidst darkening clouds. He could revisit the former site of his emotional and intellectual imprisonment, for an instant, and likewise leave it in an instant, returning to the long-desired life of freedom that he had earned through his toil and his willingness to gamble on a better future. For Edwin, such a juxtaposition of life before and life afterward filled him with gratitude and joy. While these feelings were greatly tempered by the loss of David, they likewise helped him to endure it.

Edwin’s trip to Popular Science Monthly reflects as well another interesting juxtaposition. In 1941, October 15 had for the Teales, with Edwin’s departure from Popular Science Monthly, become their personal Independence Day, a holiday they would celebrate yearly for the remainder of their life together. On July 3, 1945, Edwin’s visit with his former colleagues, one day after the completion of The Lost Woods, was followed a day later by the American holiday of Independence Day, July 4. The Fourth of July had special significance only two months after VE-Day. For most Americans, it was a day to celebrate a long-sought victory, but for the Teales the day was bittersweet at best. Not surprisingly, they spent the entire day in the shelter of the Insect Garden: “Today was as perfect a Fourth as the cloud that hangs over our spirits would permit. All day long in the open at the garden, sitting at a wooden table I found under the wagon shed and catching up on entering my Nature Notes, taking pictures, juggling around the order of the chapters and so forth.” It was, Edwin added, “A ‘Thoreau Day’—unhurried and out-of-doors.”[xxxiii] Nellie, who was and always would be Edwin’s working partner in his writing life, read and offered comment on ten of the new chapters in The Lost Woods. Such an unhurried day was a rarity. “Tomorrow,” Edwin wrote, “I begin the grind—revision and copying—that must get the book in before the end of this month!”[xxxiv] Were David returning, this Fourth of July might have been near-perfect. Edwin knew, however, that he would not, and this fact was driven home the following day when several more of their letters to David were returned. These too were marked “Deceased” but lacked the previous change to “Missing.” On each letter, to the hand-written word “Deceased” was added a jarring one-word postal stamp: “Verified.”[xxxv]

* * * * * * *

Burying himself still deeper in his labors on the book, Edwin set for himself a schedule that would bring The Lost Woods to its final form by July 26. It required the revision and retyping of thirty chapters in twenty-one days. With the mass of assisstive computer technology available to us in the twenty-first century, along with the unprecedented access to information provided by the Internet, we are largely ignorant of the sheer physical labors that an author undertook in 1945 to bring a book to publication. We can do a great deal more, now, with less labor, but one wonders if the ease of publication has largely contributed to us doing considerably less with the more we have been given. For Edwin to remain on schedule, he would have to type an average of two revised chapters per day. On July 5, despite the emotional drain of the return of their letters to David, Edwin finished two chapters.[xxxvi] On the following day, he completed “The Striking Serpent” and “On the Trail of Thoreau,” bringing the total to four and keeping him on schedule. It was a good start, and Edwin, realizing that speed and efficiency were critical if he was to maintain this pace, devised “with paper clips and an empty velour Black box […] a ms. holder that holds the sheet I am copying upright and aids me greatly.”[xxxvii]

The following day, July 7, Edwin managed to type three additional chapters. “Laboremus!” he declared at the opening of his Guild diary entry for that day, a Latin word meaning “Let us do our work!” Later in the century, the phrase “Laboremus! Let’s get to work!” was widely attributed to twentieth-century historian Arnold J. Toynbee as a favored motto.[xxxviii] For Edwin, however, at the end of the first week of July in 1945, it was less a life philosophy and more a pragmatic necessity. His completion of three chapters on the previous day allowed him, on July 8, to embark on a 7 a.m. “fishing trip on the bay with the Verity’s,” Baldwin neighbors. It was, Edwin noted, a much-needed “good time and good rest.” Returning home by 2:00 in the afternoon, Edwin slept for several hours, rising at 4:30, “half asleep,” and began typing “The Mystery of the Vanishing Flies,” finishing it by 8:00 that evening.[xxxix] This kept up the needed rate of two retyped chapters completed per day, a pace he managed to maintain on July 9 and 10 as well.

“No word of David—expected July 2 letter from Government,” Edwin noted on July 9.[xl] In the April 3 confirmation letter that followed the telegram notifying the Teales of David’s MIA status, Major General James Alexander Ulio of the War Department had written, “If no information is received in the meantime, I will communicate with you again three months from the date of this letter.”[xli] Those three months had elapsed, with one week added. Though certain of its contents, Edwin likely feared that the arrival of this letter—certain to mirror the official communications received by the Strohs and the Alvears—might cripple his ability to keep to the demanding schedule of the days ahead. It would be a staggering, final blow. Edwin’s feverish work during this time to bring The Lost Woods to completion was in part a race against the arrival of that blow, especially now that the book was nearly done. Just as he had worked diligently throughout the day before V-E Day—“…in case there is bad news I will have that much done and that will help”—he did so again on July 9.

On July 10, CBS Radio called to invite Edwin to be a guest “on the ‘Invitation to Learning’ program…on Maeterlinck’s ‘Life of the Bee.’” The Nobel Prize-winning Maeterlinck had written to Edwin after the latter’s 1940 publication of The Golden Throng: A Book About Bees, declaring, “This will be the Bible of the Bees!” The praise, Edwin noted, “lifted my feet off the ground for a moment….”[xlii] With authentic regret, Edwin declined the CBS Radio invitation, knowing he would “need every minute for my own book!”[xliii] Having completed two more chapters, he retired to bed at 6:00 that evening with a sore throat and fever—the strain of his working pace taking its toll—and spent some time “going over chapters in bed.”[xliv] Twelve chapters were retyped in their final form, with eighteen remaining. As of July 12, there was still “no word from government on Davy,” and Edwin spent the day working on “Men of Nature,” completing it by 2:30 that afternoon.[xlv] Combined with his work of the previous day, he was up to fourteen completed chapters. The next day, he completed two more: “Crocodile Dragover” and “A School for Foxes.” “Hurray!” he declared on July 13.[xlvi] By the following day, with a thorough revision of “In the Heart of a Cloud,” he was “on schedule or a little ahead of it,” feeling “pretty good.”[xlvii] In the afternoon he went to the Insect Garden, where he photographed a “yellow swallowtail” butterfly. These were the productive days in which Edwin had reveled for many years, and he did so now, despite his grief.

Edwin awoke on July 15, a Sunday, to what would be daylong rain. He stayed in bed until after 9 a.m. following “a sleepless night with dreams of David.”[xlviii] On the previous day, he had begun the final retyping of “The Lost Woods,” the book’s opening chapter. In it, he recalled simpler days spent with Gram and Gramp Way at Lone Oak. He retold the story of a trip by horse-drawn bobsled with Gramp Way “to a distant woods” to gather stored stove wood. Growing weary of loading the sled, Edwin, then six, had “wandered about, small as an atom, among the great trees—oak and beech, hickory and ash and sycamore.” He had been “at once enchanted and fearful,” and the experience made “a profound impression” on the six-year-old boy, filling him with “an endless curiosity about this lonely tract and all of its inhabitants.”[xlix] Edwin had searched in vain for these woods with his childhood friend Dewey Gunder on March 16, 1945 during his Midwestern lecture tour[l]—forty years after his only visit to them, and the same day David was declared missing. It is hardly surprising that Edwin’s dreams the previous night were occupied by David, to whom, like the lost woods of childhood, Edwin could not return except in memory—the inadequate, longing-filled shell of former joys.

Edwin spent time that day revising only the “first page and a half of ‘The Lost Woods’” before shifting his attention—perhaps because of his deep emotional connections to the chapter—to “Boundaries of the Night,” on which he spent time “revising and inserting more natural history.”[li] Edward H. Dodd Jr. had suggested in March that the book as a whole, while representing Edwin’s finest work to date, was in need of “more natural-history facts.”[lii] By early afternoon, the eighteenth retyped chapter was done, and he read for several hours in Volume II of Thoreau’s journals, a shelter from the emotional rigors of a difficult day.[liii] That evening, Nellie read to him from J.S. Fletcher’s detective novel The Box Hill Murder, which, Edwin noted, “relaxes my mind—just what I needed.”[liv]

By July 19, Edwin had revised and retyped twenty-one chapters in fourteen days, 223 pages in total. He was up at 5:20 a.m. after a “wakeful night.” He reviewed some of Nellie’s corrections and set about preparing the first two-thirds of the final manuscript for submission to Dodd, Mead for the production of galley proofs. He ordered and numbered the pages and by noon had “the whole thing wrapped up in its Keeboard ‘The Lost Woods’ box to deliver.”[lv] He took the 12:45 train into the city and arrived in a downpour, taking “muggy, stifling subways by round-about way” to Dodd, Mead’s 28th Street office, probably to keep the manuscript—not himself—out of the rain as much as possible. During a “good meeting” with Edward H. Dodd, Jr., the latter suggested a possible reissue of a revised version of Edwin’s 1942 Byways to Adventure. He also asked Edwin to “supply photos and [an] introduction” for a forthcoming reissue from Dodd, Mead of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden[lvi]—a project which, for Edwin, was especially meaningful in light of recent events. Dodd certainly knew this, and the offering of this project—or at least its timing—may have been intended in part as a modest balm for Edwin’s great suffering, an occupier for a troubled mind and heart. Back in Baldwin by 4:30 that afternoon, Edwin and Nellie went to the theater to celebrate the accomplishments and the future prospects of the day, both of which gave further shelter from, or perhaps tolerable passage through, the present darkness.

Following the celebration of the previous evening, Edwin went directly back to work on July 20, faced with the revision and retyping of nine chapters in seven days. With the arrival of confirmed news of David’s death seeming imminent, his grief-laden efforts were all the more daunting but likewise critical. After a short early-morning trip to the Insect Garden, he began to organize his materials for the remaining chapters. His fatigue of the recent weeks, however, made sustained work difficult, and he had to lie down and rest for an hour. “If I can get one chapter copied somehow today,” he noted, “will keep on my schedule.” He managed only to type out half of the “Snowflake chapter…in sweltering heat” and quit for the day.[lvii] That night, he garnered his optimism as best he could. “Rested now,” he wrote, “and ready to go!”[lviii] On the following day, however, his fatigue set fully in. With great exasperation, he wrote, “Copy page 1 of ‘Wildlife at Walden’ over 10 times—making typing mistakes over and over. Ready to go through the roof!”[lix] Here again we are reminded of the absence of a delete key in 1945. “My head like a rock,” he lamented, “with heat and fatigue—residue.”[lx] Residue. The residue of longing; the residue of trampled hopes; the residue of time’s indifferent forward march. Still, by evening he had finished the chapter and even took time to mull over plans for “a new book on the injurious insects.”[lxi] Of necessity, he kept his gaze forward.

While toiling away on the first full draft of the The Lost Woods, Edwin had put off writing “The Calm of the Stars”—what the reader might reasonably call the David chapter—until the end. On July 22, however, after a quick trip to the wagon shed at the Insect Garden “to photograph baby swallows,” he set to work on revising it ahead of the other six chapters that remained to finalize. He wrote only one sentence on this effort in the Guild diary: “Fall to on ‘The Calm of the Stars’ and finish it before lunch.”[lxii] With the looming likelihood of receiving confirmation of David’s death—both from the War Department and an expected letter from PFC Harold F. Gould Jr.— Edwin likely strove to complete the chapter as quickly as he could. On the previous day he had expressed his “hope to go faster after today,” and he did so. After completing “The Calm of the Stars,” he went on to revise and retype another chapter. “Five chapters to do in four days,” he noted, “then all will be done!”[lxiii]

The next day, following the pattern of recent weeks—an alternating rhythm of productivity and debilitation—Edwin fell prey to the latter:

Up feeling dead-headed. The successive days of rain; the high-pressure work; the strain of David; the suspense of waiting for a call from Harold Gould—the returning member of Davy’s patrol—and the call from Dodd on how he liked the first 21 chapters—all combined to stall my engine completely.[lxiv]

In total, Edwin completed “less than 2 pages on ‘World of the Wild Bee,’”[lxv] disheartening output in light of the revision timeline for the final chapters. Edwin was likely forthright about his struggles with Edward H. Dodd, Jr. during a telephone call later that day. He noted afterward, “I get a reprieve; don’t have to hand the final chapters in until next Monday.” Feeling relieved, he and Nellie went out to see a movie and were in “bed and asleep by 9” with the “hope to do better tomorrow!”[lxvi] That hope would not, however, come to fruition.

* * * * * * *

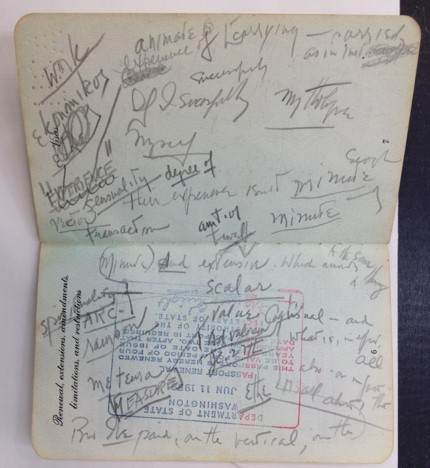

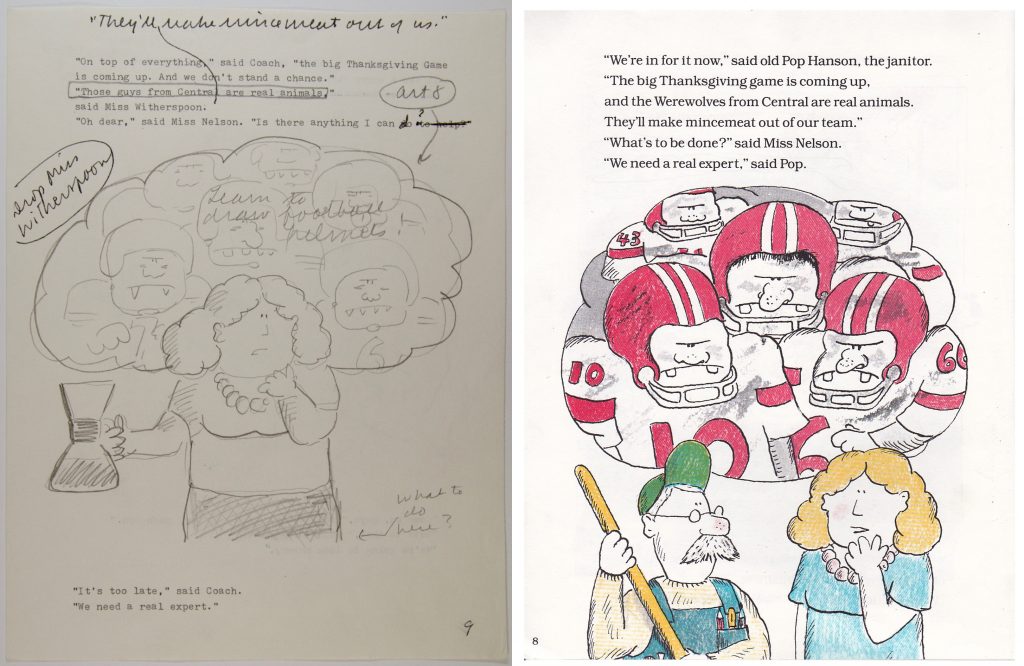

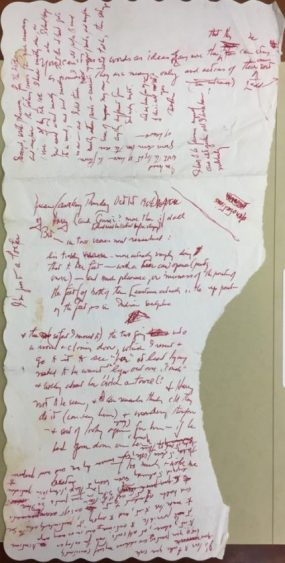

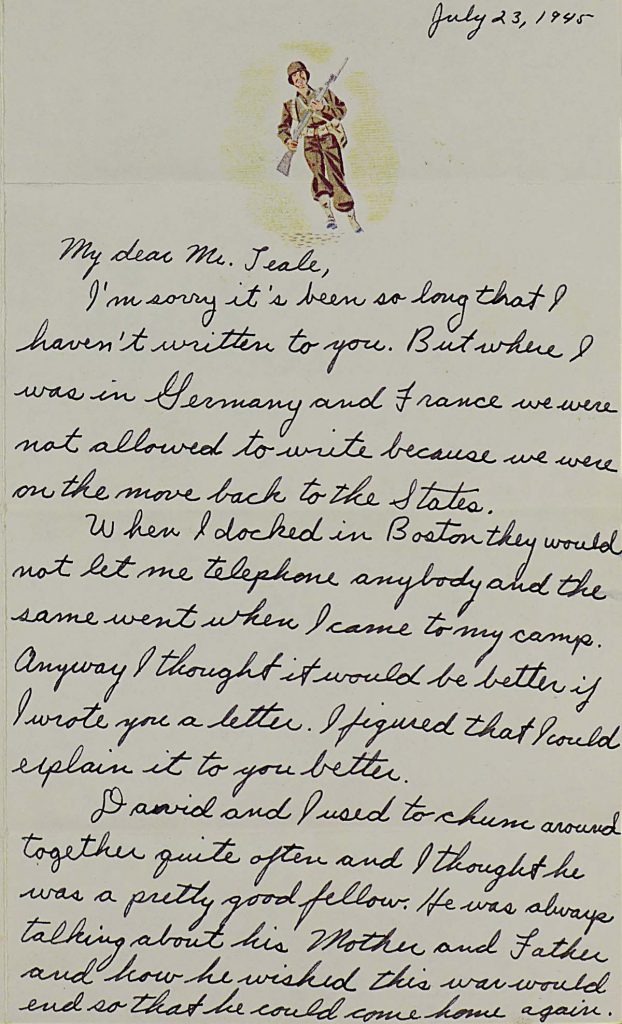

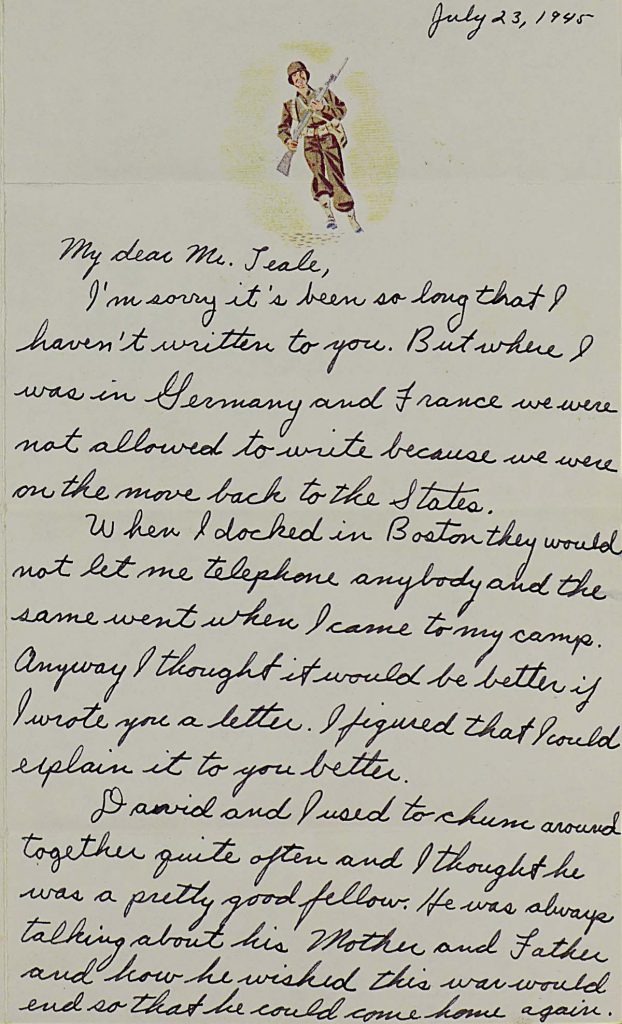

On July 24, 1945, the storm cloud that had loomed since April 2 finally and fully broke open. There would be no word from David, not now, not ever. There would be only word of David, and it would come first from Harold F. Gould, Jr., of Plymouth, Massachusetts, in a letter written on small stationary whose only letterhead was the figure of a running G.I. clad in drab fatigues and clasping an M1 Garand rifle, bayonet mounted, a field bag trailing from his ammunition belt. The soldier grins at the letter’s reader—a mask muting the “unredeemed horrors” of war—and that grin must have made the Teales shudder.

The first page of a letter sent by Private First Class Harold F. Gould, Jr. to Edwin Way Teale on July 23, 1945. Gould explained the events leading up to the March 16, 1945 death of David Teale on Germany’s Moselle River during the closing days of World War II.

Gould began by apologizing for not calling, as camp prohibitions had forbidden doing so. “Anyway,” he wrote, “I thought it would be better if I wrote you a letter. I figured that I could explain it to you better.”[lxvii] He wrote of how he and David “used to chum around together quite often,” and how the Tiger Patrol “did mostly night work.” In that capacity, Gould added, David “was very courageous,” and “all the boys liked Dave very much.”[lxviii] These formalities aside—and one imagines the Teales having the impulse to skip over them while, at the same time, dreading to do so—he came “down to the point” and detailed the events that led to David’s death on the Moselle River:

We had received our orders from commander that we were to cross the Mosel[le] River and get some important information that we needed for the attack. We had twelve men in the patrol and four rubber boats. Three men were assigned to each rubber boat. We had been broken up into two six man patrols. We all started in our rubber boats across the river, just as the boats were nearing the enemy side we were opened up on by machine guns. The boys shot back at them until they ran out of ammunition. Then they withdrew so that they could get more ammunition. They came back again and started in their boats across. They met heavy opposition and the boats were sprayed with bullets. Some of the compartments in the rubber boats were shot to pieces so I guess the boys got a little excited when they saw this so they started jumping over. That was their gravest mistake…Especially for Dave because before he went on this patrol he told us he couldn’t swim. He still volunteered to go on the patrol and I’ve always admired him for that.

The last time they ever saw Dave he was in the water calling for help but none of the boys could reach him because he went under this time and never came up. It’s very strange that the army couldn’t find his body.[lxix]

To this account, Harold Gould added a second reference to David’s inability to swim:

If David could swim he would have had a good chance of coming out alive. I still remember what he said before we went on patrol. He said “I don’t know how to swim but I’ll volunteer to go on patrol.[”]

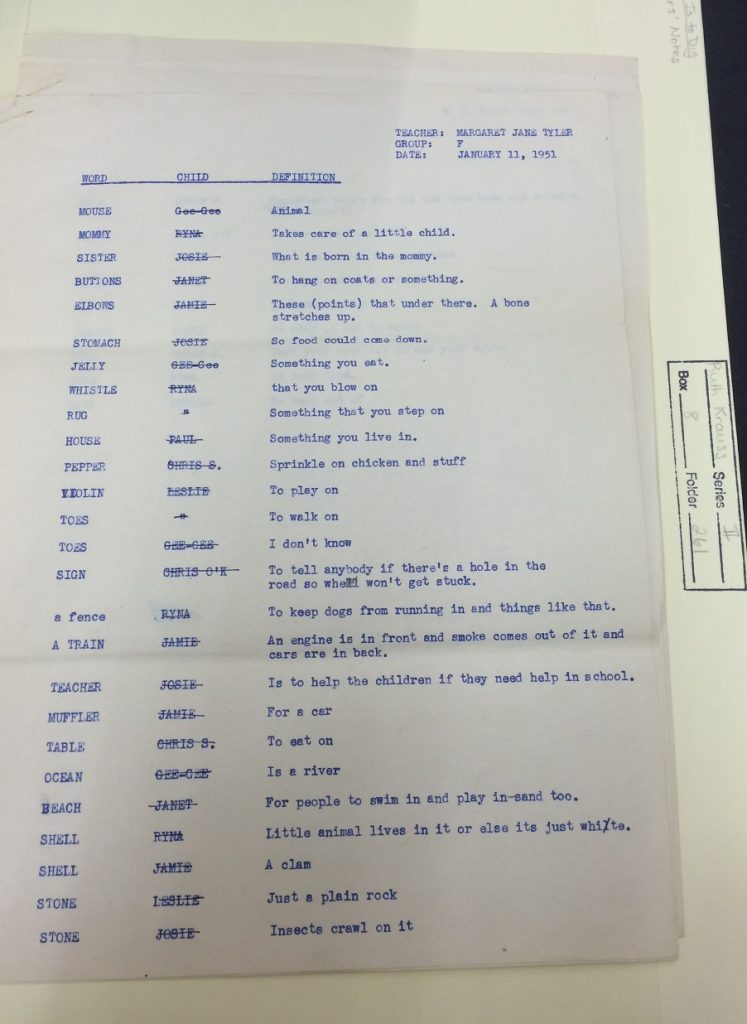

This must have confused the Teales greatly. David was, by Edwin’s account, a strong swimmer, a fact supported by a Boy Scouts of America patrol record book among David’s personal belongings. In it, David, as Patrol Leader, had tracked the rank advancements of all of the boys in the Flying Eagle patrol, including himself. On the merit badge roster, beside David’s name, the requisite boxes are checked off for the swimming and lifesaving merit badges.

Harold Gould closed:

I liked your son very much Mr. Teale and I was very proud of him. I know you will always be too.[lxx]

Such a statement, though well-intentioned and certainly appreciated, was nonetheless an arrow to the heart. In mid-April, when hope still lived, Edwin had written of David, “He is one of which we are proud in so many ways. And, viewed from the most distant star—remote from our emotions and longings—that is all that counts.”[lxxi] But David’s return, alive, had also counted; so too had the bright future before him—the long walk down the Pacific coast, the possibility of future matriculation at Earlham, the return to Weller Pond, and so much more. All of these would never be. No pride could mitigate the staggering loss of David’s future. “This is it!” Edwin wrote after reading Harold Gould’s letter, “How terrible we feel.”[lxxii] The news was not official, but it was sufficient, and it would be confirmed days later by a letter from PFC Lester Snider, the last Tiger Patrol member to see David alive. There is no record of Edwin having completed any work on The Lost Woods on July 24; even that labor of his heart could offer no refuge. As if an insult to their grief, the afternoon brought the return by special delivery of the package in which Edwin had sent David the Grenfell parka in March, eight days before the latter’s death. It was one more manifestation of a future that would not be. Boxed in thick lines of black ink, Edwin wrote the following in the Guild diary:

On this day hear definitely, but unofficially, that David was killed on the Moselle River near Coblenz, Germany, on the night of March 15-16, 1945—

To this he added a bracketed postscript:

How long and how devoutly I hoped this entry would not have to be made![lxxiii]

No tears stain this page. Harold Gould’s letter offered not a revelation but a confirmation of what, in their hearts, Edwin and Nellie already knew. Edwin Stroh’s death had confirmed David’s, and both had been foretold by the death of Antonio Alvear. Harold Gould’s account, though vitally important to the Teales, could serve only as a coda. They certainly cried on July 24, 1945, but they did so in the privacy of their own collapsing world. Edwin left no trace of those tears to revisit later, neither through the narrative of his words nor through their partial dissolution by tears on the page. It is an apt analogy for the turning inward that would follow, both from the greater world and, despite their mutual devotion, often from each other.

* * * * * * *

The day after receiving Harold Gould’s letter, Edwin reached him by telephone. Gould shared that “only 4 out of 12—only 1 out of 6 with David’s 2 boats—returned alive after crossing the Moselle.”[lxxiv] One of those four, PFC Lester Snider, of Hennessey, Oklahoma, had been in charge of David’s boat and was “the last one to see David alive.”[lxxv] Snider had returned home, and Edwin wrote to him that afternoon. “Our son, David Teale, was reported missing in action on March 16th,” Edwin began, “and we have had no word from the government since….I have learned that you went across at the same time David did and that you were the last person to see him alive. If you can give us any information about what happened, we will be most deeply grateful.”[lxxvi] Snider received Edwin’s inquiry on July 30 and replied the following day, offering his account:

Six of the boys including your son David volunteered for reconnaissance patrol. We crossed to the east of the Mosel[le] River in two boats. Your son David + another boy were with me in the one boat. We made a successful reconnaissance of enemy positions + possible landing places.

While making the return trip across the river we encountered heavy enemy machine gun + sniper fire. Our boat was hit + sank. And one of the boys was hit but don’t know exactly which one. The last I saw of either of the boys was when they went over the side of the boat into the water.[lxxvii]

Just as Gould had done, Lester Snider praised David’s selflessness: “I didn’t know your son very long Mr. Teale. But he was well liked by all the boys. And he was a son to be proud of. He didn’t have to go on this mission, but realizing the danger, volunteered to do so.”[lxxviii] David had volunteered; for this he had died. Although Edwin, half a year earlier, had written of war death that “the collapse of character alone was tragedy,”[lxxix] this abstract philosophy abruptly withered with David’s death. David’s character had not collapsed on the night of March 15, 1945; his courage and his character had towered above those of others. For this David had died, and his death was a tragedy. His life, no matter how its worth had been elevated by his actions, was no less “a plaything of fate,”[lxxx] and this embittered Edwin terribly. “All hope gone,” he wrote. “Life goes on no matter how heavy the heart! Life outlives the joy of life; the spring is wound up and, normally, has to run down. And it can’t be rewound.”[lxxxi] David’s spring had not run down. It never would. It had been cracked by the violent folly of war, and with that fracture had gone all the youthful tension of future possibility.

Richard Telford has taught literature and composition at The Woodstock Academy since 1997. In 2011, he helped found the Edwin Way Teale Artists in Residence at Trail Wood program, which he now directs. He was a long-time contributing writer for The Ecotone Exchange. He was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant by the University of Connecticut to support his work on a book about naturalist, writer, and photographer Edwin Way Teale. The Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees likewise granted him a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year to support this work.

References

Farrer, Reginald. The Void of War: Letters from Three Fronts. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1918.

Frankel, Max. “150th Anniversary: 1851-2001; Turning Away From the Holocaust.” The New York Times 14 November 2001. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/14/news/150th-anniversary-1851-2001-turning-away-from-the-holocaust.html

Gould, Harold F. Jr., Letter to Edwin Way Teale, 23 July, 1945, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Gould, Walter F., Letter to Edwin Way Teale, 16 June, 1945, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

“Ecleasiastes.” The Holy Bible: Revised Standard Version: New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1952.

Ikeda, Daisaku. The Third Stage of Life: Aging in Contemporary Society: Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press, 2016.

Parker Pen Company. Advertisement. The Saturday Evening Post. 1 April 1945.

Snider, Lester L., Letter to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 31 July 1945, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Snider, Lester L., Letter to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 21 August 1945, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, Letters to Edwin Way, Nellie Donovan, April to December, 1944, Box 146, Folder 2949, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, David Allen, Letters to Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan Teale, 1945, Box 146, Folder 2950, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living: Volume II, unpublished journal, February 1944 to May 1946. Box 113, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan, Letters to David Allen Teale, 1944, Box145, Folder 2941, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way and Nellie Donovan, Letters to David Allen Teale, 1945, Box145, Folder 2942, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary, 1945. Box 99, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way, Letter to Herbert F. Schwarz 25 May 1942, collection of the author.

Teale, Edwin Way. The Lost Woods. New York: Dodd, Mead , and Company, 1945.

“Tiger Patrol First to Enter Koblenz.” Unsigned news clipping, 1945, no bibliographical information noted.

Ulio, James Alexander, Letter to Nellie Donovan Teale, 3 April, 1944, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Witsell, Major General Edward F., to Nellie Teale, letter, 25 February 1946, Box 146, Folder 2952, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Notes

[i] Ecclesiastes 1, 9-13. The Holy Bible: Revised Standard Version: New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1952.

[ii] Farrer, Reginald. The Void of War: Letters from Three Fronts. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 37-8.

[iii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 3 January 1945.

[iv] Parker Pen Company. Advertisement. The Saturday Evening Post. 1 April 1945.

[v] Teale, David Allen, to Nellie Donovan Teale, letter, 1 November 1944.

[vi] Teale, David Allen, to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 16 November 1944.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 8 August 1945.

[ix] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 18 June 1945.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 20 June 1945.

[xiii] Gould, Walter F., to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 16 June 1945.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 22 June 1945.

[xvi] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, letter, 18 July 1944.

[xvii] Teale, Edwin Way, to David Allen Teale, letter, 29 July 1944.

[xviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 23 June 1945.

[xix] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 28 June 1945.

[xx] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 18 June 1945.

[xxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 28 June 1945.

[xxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 24 June 1945.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 25 June 1945.

[xxv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 27 June 1945.

[xxvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 1 July 1945.

[xxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 2 July 1945.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 3 July 1945.

[xxx] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 25 August 1945.

[xxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 4 May 1945.

[xxxii] Frankel, Max. “150th Anniversary: 1851-2001; Turning Away From the Holocaust.” The New York Times 14. November 2001.

[xxxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 4 July 1945.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 5 July 1945.

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 6 July 1945.

[xxxviii] Ikeda, Daisaku. The Third Stage of Life: Aging in Contemporary Society: Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press, 2016.

[xxxix] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 8 July 1945.

[xl] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 9 July 1945.

[xli] Ulio, James Alexander, to Nellie Donovan Teale, letter, 3 April 1945.

[xlii] Teale, Edwin Way, to Herbert F. Schwarz, 25 May 1942.

[xliii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 10 July 1945.

[xliv] Ibid.

[xlv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 12 July 1945.

[xlvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 13 July 1945.

[xlvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 14 July 1945.

[xlviii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 15 July 1945.

[xlix] Teale Edwin Way. The Lost Woods. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1945. 1-3

[l] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 16 March 1945.

[li] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 15 July 1945.

[lii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 6 March 1945.

[liii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 15 July 1945.

[liv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 12 July 1945.

[lv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 19 July 1945.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 20 July 1945.

[lviii] Ibid.

[lix] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 21 July 1945.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 22 July 1945.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 23 July 1945.

[lxv] Ibid.

[lxvi] Ibid.

[lxvii] Gould, Jr., Harold F., to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 23 July 1945.

[lxviii] Ibid.

[lxix] Ibid.

[lxx] Ibid.

[lxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 18 April 1945.

[lxxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 24 July 1945.

[lxxiii] Ibid.

[lxxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 25 July 1945.

[lxxv] Ibid.

[lxxvi] Teale, Edwin Way, to Lester L. Snider, letter, 25 July 1945.

[lxxvii] Snider, Lester L., to Edwin Way Teale, letter, 31 July 1945.

[lxxviii] Ibid.

[lxxix] Teale, Edwin Way. Adventures in Making a Living, Vol II. 3 January 1945.

[lxxx] Ibid.

[lxxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Guild diary 1945. 4 August 1945.

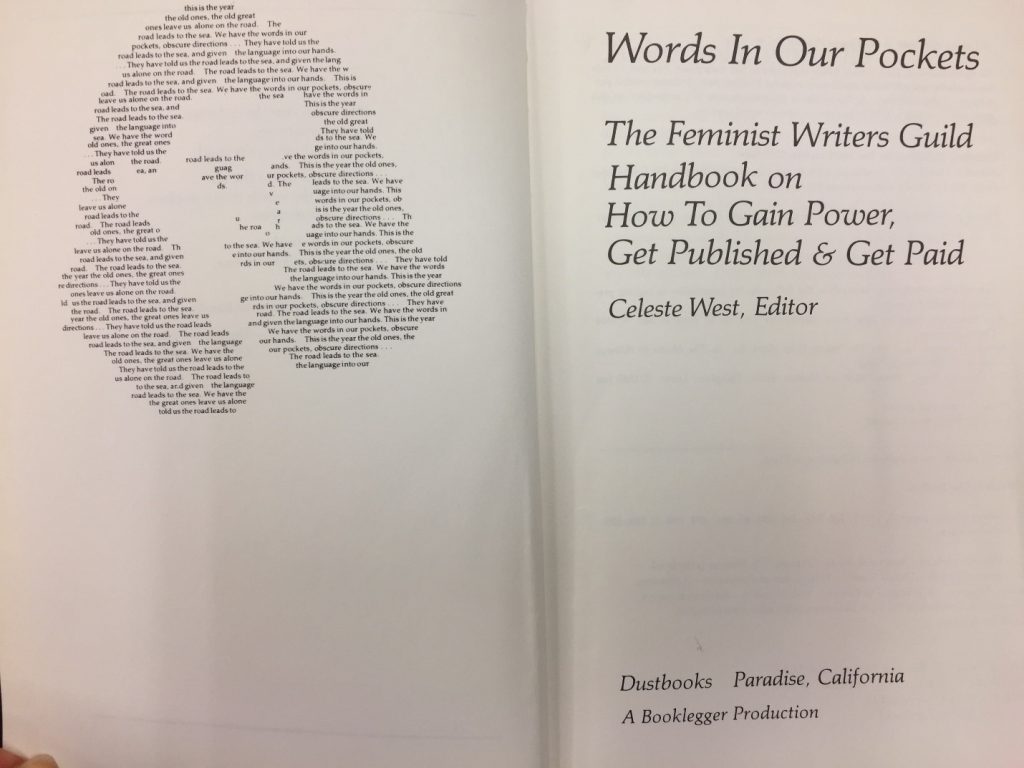

In 1985, noted librarian and author Celeste West published a book titled “Words in Our Pockets: The Feminist Writers’ Guild handbook on how to gain power, get published & get paid.” The book provided an in-depth look at the publishing world through a feminist lens and provided women with resources and options for alternative paths to publication.

In 1985, noted librarian and author Celeste West published a book titled “Words in Our Pockets: The Feminist Writers’ Guild handbook on how to gain power, get published & get paid.” The book provided an in-depth look at the publishing world through a feminist lens and provided women with resources and options for alternative paths to publication.

In the spring of 1971, “Aphra” had a special “Whore Issue”. This issue dealt with problems of women being condemned for sexual promiscuity as well as the exploitation of women as sex workers.

In the spring of 1971, “Aphra” had a special “Whore Issue”. This issue dealt with problems of women being condemned for sexual promiscuity as well as the exploitation of women as sex workers.