For 25 years, the Connecticut Children’s Book Fair has welcomed families, collectors, teachers, students and librarians to UConn to meet and to hear talented, award-winning authors and illustrators discuss their work. This weekend on November 4 and 5, we are excited to once again foster the enjoyment of reading among Connecticut’s youth with two days of dynamic programming. The Book Fair takes place at the Rome Commons Ballroom on the UConn campus — visitor information can be found on the event website.

Archives and Special Collections celebrates the Connecticut Children’s Book Fair in this milestone year by featuring the collections of authors and illustrators found in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection (NCLC). The Book Fair is also an opportunity to highlight recent research conducted in the papers and archives of NCLC authors and illustrators.

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut.

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut.

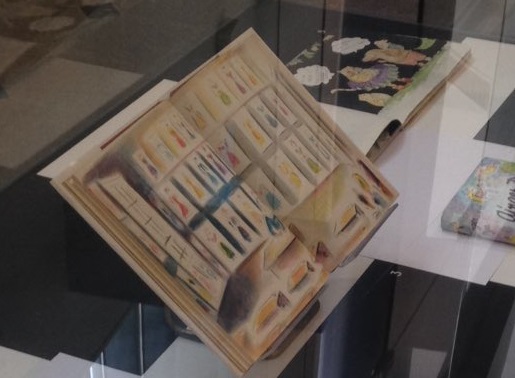

The Northeast Children’s Literature Collection was developed in 1989 to collect and preserve the history of children’s literature and illustrations, and comprises the archives of over 120 notable authors and artists. Among completed editions of beloved children’s books, the collection also includes countless preliminary sketches, letters, dummies, manuscripts, notes, and correspondence with family, editors, and other writers and artists.

The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

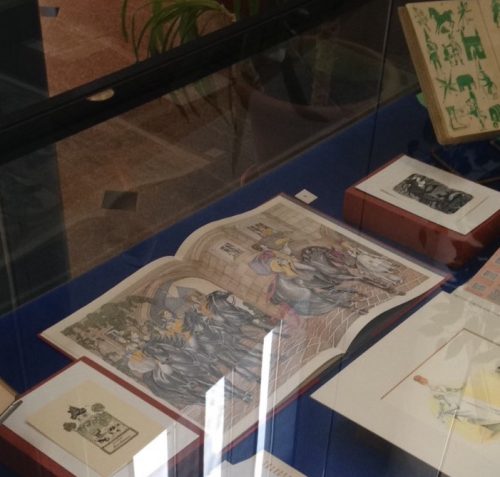

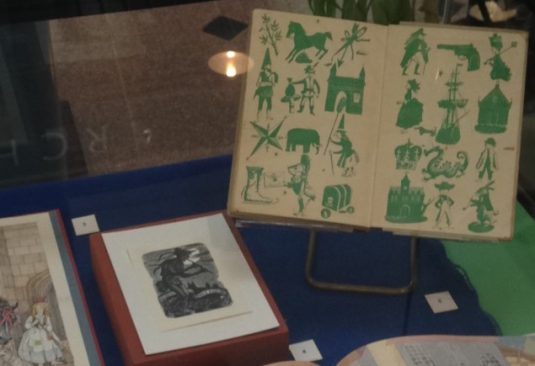

The objects on display in Archives and Special Collections represent just some of the archival materials past Fellows and Grantees have found noteworthy in their research. These objects also dialogue with others in Archives and Special Collections, and together offer rich and surprising stories of classic tales.

The collection’s extensive and cross-historical nature provides a visual and narrative mapping of the perseverance of certain character types and situations. One of the most persistent topics of interest in children’s literature concerns problems that arise from class conflicts, and the tensions between members of the aristocracy, bourgeoisie, and working class communities. Where a character is from and the spaces they are permitted to navigate reveals much about their personality, goals, and interactions with other characters in their environment. These works show desire and punishment, as characters’ morality largely dictates whether they are granted social mobility or afflicted with poverty or other penalties.

Even if clear moral distinctions between classes are not drawn, the picturing of difference is almost always apparent. The objects displayed in Archives and Special Collections represent a sampling of the visualization of class and “otherness” in popular children’s fables and fairy tales, as well as the ways in which characters’ bodies, properties, and reputations are threatened by these factors.

We encourage exploration of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, or explore the blog for Archives and Special Collections, to learn more about scholarship conducted by visiting academics, writers, and artists.

– Nicolas Ochart

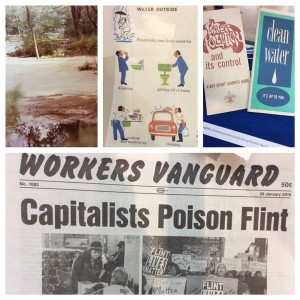

Building towards the Presidential Election in November 2016, Students in ENGL 1010S: Seminar in Academic Writing considered different definitions of “leadership.” The final project asked students to think critically about leadership historically through particular artifacts from the Archives & Special Collections

Building towards the Presidential Election in November 2016, Students in ENGL 1010S: Seminar in Academic Writing considered different definitions of “leadership.” The final project asked students to think critically about leadership historically through particular artifacts from the Archives & Special Collections