Mrs. Belcour. Come, come, cheer up; endeavour to forget that Manly ever lived.

Belinda. Never, madam ! The only consolation I can afford myself is, that he fell fighting those battles which must for ever remain imprinted on my heart.

Mrs. Belcour. Yes: he with your gallant father fell by their noble general’s side on Egypt’s shores ; with him they conquered, and with him they fell. (Hook 7)

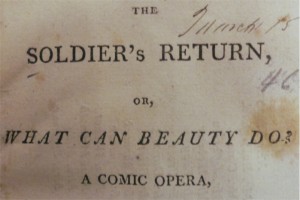

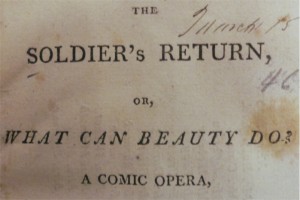

When you are reading a British comedy from 1805—and the comedy is titled The Soldier’s Return, and you have just learned that poor Belinda our protagonist is about to be “married to-night” (4), to a certain Lord Broomville, and believes that now “all my ideas of future happiness are crushed—destroyed” (7)—and then read the above exchange, learning that Belinda’s intended is believed to be dead, you can immediately conclude that the man’s resurrection is imminent.

When you are reading a British comedy from 1805—and the comedy is titled The Soldier’s Return, and you have just learned that poor Belinda our protagonist is about to be “married to-night” (4), to a certain Lord Broomville, and believes that now “all my ideas of future happiness are crushed—destroyed” (7)—and then read the above exchange, learning that Belinda’s intended is believed to be dead, you can immediately conclude that the man’s resurrection is imminent.

I mean, come on. A dead lover and an unhappy arranged marriage to an older man? In the world of comedy, the dead man can’t resurrect fast enough in such a situation. You just need to pay attention, and wait and watch for his return. And sure enough: in Theodore Hook’s The Soldier’s Return, the soldier returns after only about three scenes, and, of course, to his own distress, “I have found Belinda, the object of my hopes and anxiety, on the eve of marriage with a lord Broomville” (11).

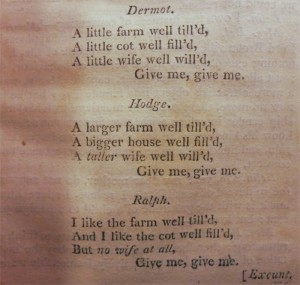

Thus we have all of the things you need for a standard comedy, with the true lovers separated by forces outside of their control, who ultimately, of course, reunite through a series of implausible events. It’s predictable, yes, but ultimately it’s really all about how we get there to this end, and this play does so in the most amusing and unpredictable methods possible. Theodore Hook, our playwright, has a sharp wit, and the play excels at the mockery of the British upper crust, with aristocrats saddled with ridiculous names like Lord Broomville; with young foppish men dressed so absurdly in “the present slang fashion” (10) that the lower class can “take a fellow of the royal society for a groom” (10); and with supposedly cultured people who “positively abominate” (20) the opera, yet “every body goes, and ’tis the every body that makes it delightful” (2).

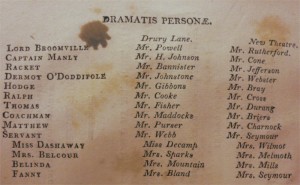

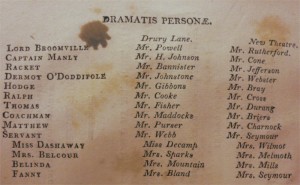

The American edition of the text includes a list of both British and American casts

Unfortunately, though the play was performed in London in 1805 at Drury Lane, Hook himself seems to have received little press for this play, possibly because of his age. “[The Soldier’s Return was] his first effort” (Barham 14), and “placed the author in the proud position of a successful dramatist—ætat 16” (14), but I could find no contemporary reviews, merely affectionate but nonspecific references to Hook himself, as “that lively young author” (“The Arbitrator” 183). The play received apparently little notice, and his own biographer too gives only backhanded praise, saying “inartificial as was the plot, and extravagant the incidents. . . the whimsicalities of an Irishman, played by Jack Johnstone, the abundance of puns, good, bad, and indifferent, borrowed and original, the real fun and bustle, carried it along triumphantly” (Barham 14).

In America, it was “performed at the New Theatre, Philadelphia” (1) in 1807, but here too, no one took notice of The Soldier’s Return, though its top-billed actor, a Mr. Rutherford—who played Lord Broomville—seems to have attracted some attention in other roles. One William Wizard calls him “Little RUTHERFORD, the Roscius of the Philadelphia theatre” (Wizard 117), which makes little sense until one sees a different article, which says “this gentleman’s person is much in the way of his theatrical success ; and, indeed, when, one after the other, so many individuals present  themselves on the boards, all below hero-measure, we cannot but lament it deeply that no expedient can be thought of, for adding to their inches” (“The Theatre” 1). It seems Rutherford was a short man, and, since William Wizard also writes satirically that a great critic “finds fault with every thing—this being what I understand by modern criticism” (Wizard 117), this was a problem.

themselves on the boards, all below hero-measure, we cannot but lament it deeply that no expedient can be thought of, for adding to their inches” (“The Theatre” 1). It seems Rutherford was a short man, and, since William Wizard also writes satirically that a great critic “finds fault with every thing—this being what I understand by modern criticism” (Wizard 117), this was a problem.

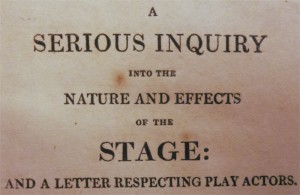

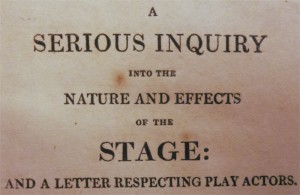

Young Hook’s play in America was thus presented in an environment of animadversion towards his lead actor, and, actually, towards drama in particular. Theater itself was  not well regarded, as an American book here in the archives, A Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage, by the Rev. John Witherspoon (1812) reveals even in its opening pages. The opening recommends that “Dear Christian Brethren. . . in the name of the Great God our Saviour, whose Disciples you are. . . WITHHOLD ALL SUPPORT FROM THE PLAY-HOUSE” (Miller et al. 5), as “in its origin and history it has been a public nuisance in society, in its present constitution it is criminal, under every form it is useless, and it must necessarily tend to demoralize any people who give it their support” (5).

not well regarded, as an American book here in the archives, A Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage, by the Rev. John Witherspoon (1812) reveals even in its opening pages. The opening recommends that “Dear Christian Brethren. . . in the name of the Great God our Saviour, whose Disciples you are. . . WITHHOLD ALL SUPPORT FROM THE PLAY-HOUSE” (Miller et al. 5), as “in its origin and history it has been a public nuisance in society, in its present constitution it is criminal, under every form it is useless, and it must necessarily tend to demoralize any people who give it their support” (5).

Nuisance, criminal, and useless? I think not, but still understand better perhaps why this play or any play may not have met great success in America at the time. Our play was merely in an environment not ready to receive it, and that needn’t hurt the play itself now. The play is really a witty romp through the aristocracy and comedy itself, coming to a completely surprising conclusion which lampoons conventional comedic formula: Manly has no choice but to challenge Lord Broomville to a duel over his intended marriage to Belinda (typical), but meeting him in person, finds that “O gracious heaven!—it is, it is——my father—!” (33).

Thus, at the end of this play we are left with a surprise which we were not expecting. The father has been in the way of the marriage all along, but we didn’t even know it, and neither did he! Hook has employed the trope of the parent preventing the marriage, and subverted it, while simultaneously subverting the trope of the duel! For such things, along with the witty exchanges, should it be remembered.

Consider this finally: A fashionable young man, Racket, asks his beloved, Miss Dashaway, “why, am I not the very top of fashion?” (23), to which she responds mockingly “yes true ; because ’tis with men as with liquors, the lightest will always be uppermost” (23). Funny, right? So, yes, perhaps this play itself may have seemed too light, but even being short, written by a sixteen-year-old, and largely forgotten, The Soldier’s Return is a gem that continually and humorously tests our comedic expectations.

Let’s not let it languish all the way at the “very top” of drama.

Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. For his blog series Hypocrite Lecteur he will spend the Spring 2014 Semester exploring nineteenth-century literature in a variety of genres from the Rare Books Collection housed in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center.

Works Cited

“The Arbitrator.” Beau Monde, or, Literary and fashionable magazine 2.14 (Nov. 1897): 181-185. Web. British Periodicals. 15 March 2014.

Barham, Rev. R.H. Dalton. The Life and Remains of Theodore Edward Hook. London: Richard Bentley, 1849. Web. Google Books. 15 March 2014.

Hook, Theodore Edward. The Soldier’s Return, or, What Can Beauty Do? A comic opera, in two acts. Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1807. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A208]

Miller, Samuel, et al. “An Address.” A Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage, Rev. John Witherspoon. New York: Whiting and Watson, 1812. Print. [Dodd Center call number: A1019]

“The Theatre.” The Town 2 (January 3, 1807): 1. Web. American Periodicals. 15 March 2014.

Wizard, William. “Theatrics.” Salmagundi; or, the Whim-Whams and Opinions of Launcelot Langstaff, Esq., and Others 6 (March 20, 1807): 117. Web. American Periodicals. 15 March 2014.