-Guest blog post by Marc Reyes, doctoral student at the University of Connecticut and 2016 Summer Graduate Intern in Archives and Special Collections.

“Now, I am a black playwright; I am not a playwright who happens to be black…I am very happy writing about black people. I do not have to write about anybody else.”

“Now, I am a black playwright; I am not a playwright who happens to be black…I am very happy writing about black people. I do not have to write about anybody else.”

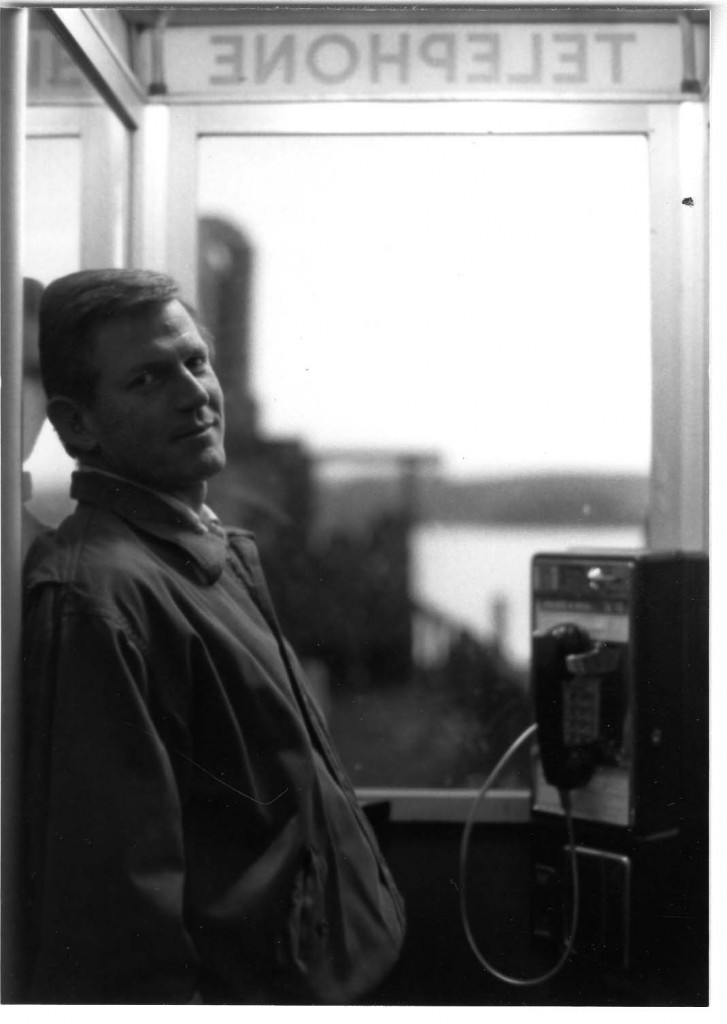

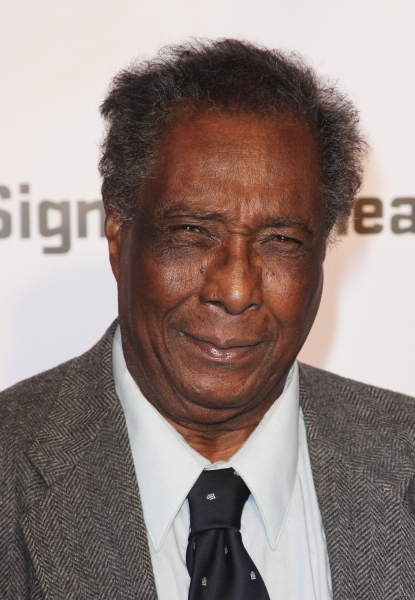

Those words were spoken by dramatist Leslie Lee, a renowned writer of stage and screen. When Lee was not scripting Tony Award-nominated plays or acclaimed television programs, he spoke to students about his life, writing career, and creative process. Lee visited the University of Connecticut on September 29, 1987 as a guest speaker for the university’s course, Black Experience in the Arts. The class, offered through the School of Fine Arts, debuted in the Fall semester of 1970 and lasted under this name until the mid-1990s. During the course’s lifetime, UConn undergraduates heard from hundreds of black artists, representing fields such as music, dance, poetry, sculpture, and architecture. Many of the invited presenters were performers with a myriad of memories and achievements as well as thoughts about what it meant to be a black artist in America. Course notes, typed lecture transcriptions, and over three hundred audio recordings are some of the materials found in Archives and Special Collections’ Black Experience in the Arts collection. This collection offers researchers an exciting look into a course dedicated to highlighting the contributions of black artists and the power of art as a mechanism for social change and racial expression. From this vantage point, scholars of the American experience gain a richer understanding of the black arts movement of the 1960s and 1970s and how black artistic expression was a crucial element of the civil rights and later black power movements.

When Lee spoke in the Fall of 1987, he was one of the few playwrights that addressed the class. Most of the speakers who represented black theater were actors or directors, but Lee offered insights into how a writer expresses their creative vision through different mediums. Of all the ways his writing was expressed – through films, television, and novels – his first love was theatre because it was the most verbal. He explained, “But in the theater it is my play and it is my vision, and those persons who are directing, or the set designers, or the costume designers, the lighting designers, the actors are an extension of me…”

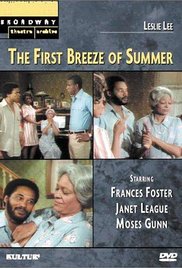

Besides discussing his career, Lee told students about his middle-class upbringing in Pennsylvania and how family members, like his grandmother, were inspirations for some of his play’s most memorable characters. He also explained how his interest in writing and the arts was not predestined, in fact, Lee confided to his audience that his artistic journey started later in life. Growing up he wanted to be a doctor and even spent years as a cancer researcher, but his passion for writing overwhelmed all else and he returned to school to study playwriting at Villanova University. After graduating, Lee worked as a writing instructor at several colleges and adapted for television Richard Wright’s Almos’ a Man. But his big break came with the staging of his 1975 play, “The First Breeze of Summer.” The production won three Obie Awards (the top honor for Off-Broadway productions) including Best New American Play and then moved to Broadway where it was later nominated for a Tony Award in the Best Play category.

In his lecture, Lee stressed to the students that to be a successful writer, one must have something important to say. Their voice must communicate a message that can even reach international audiences. With his voice, Lee strove to produce works that celebrated blackness and displayed the beauty of black bodies. He lamented seeing blacks thin their lips, alter their noses, and bleach or peel their skin to appear lighter. He remembered marching in the 1960s to the chants of “Black is Beautiful” and how the collective faith in that message erased the doubts he had about the beauty of black bodies. From that moment, he wanted his work to produce a similar feeling in black Americans. As for the characters found in Lee’s works, his heroes are the everyday black man or woman “who struggle daily against racism and against other things that are constantly impinging upon their consciousness.” Finding theatre to be the best avenue for exploring black consciousness, Lee developed an array of three-dimensional black characters that tackled issues such as systematic racism and the horrors of war.

Beyond individual depictions, Lee was also concerned in the ways black families were depicted in the arts. He believed black families, like the ones found on The Jeffersons and Good Times, were almost always portrayed in comic lights, making it easier to not take black people, and their concerns, seriously. He recounted a story about a reviewer who saw his play “Hannah Davis,” which centered on the actions of an upper-class black family. Although the work received many positive reviews, one critic panned the play. The critic found the piece problematic because he could not envision that a well-to-do black family like this existed. Lee rejected the shallow criticism and informed the reviewer that the family in the play was based on a real black family, but the experience reinforced in Lee the need to project stronger images of black people and their families than the depictions usually found on television or motion pictures.

Beyond individual depictions, Lee was also concerned in the ways black families were depicted in the arts. He believed black families, like the ones found on The Jeffersons and Good Times, were almost always portrayed in comic lights, making it easier to not take black people, and their concerns, seriously. He recounted a story about a reviewer who saw his play “Hannah Davis,” which centered on the actions of an upper-class black family. Although the work received many positive reviews, one critic panned the play. The critic found the piece problematic because he could not envision that a well-to-do black family like this existed. Lee rejected the shallow criticism and informed the reviewer that the family in the play was based on a real black family, but the experience reinforced in Lee the need to project stronger images of black people and their families than the depictions usually found on television or motion pictures.

Leslie Lee’s September 1987 visit to UConn’s Black Experience in the Arts class discussed the personal and artistic fulfillment that can be found in the performing arts and encouraged students to consider a career in drama and make a home in black theatre. For interested students, he referred to the Negro Ensemble Company which produced many of Lee’s plays and has been a training ground for black actors such as Lawrence Fishburne, Angela Bassett, and Denzel Washington. Lee asserted that more black writers and actors were needed to produce multi-dimensional and complex black characters. He also wished black students would pursue theatre criticism because he believed black critics would bring greater insights when evaluating the works of black playwrights.

There are many more exciting ideas and profound lessons found in Lee’s lecture which can be explored in the Black Experience in the Arts collection at Archives and Special Collections. Stay tuned as we continue to make these valuable materials more widely known and available as well as additional blog posts highlighting other prominent lecturers who visited the university and spoke to students about the Black Experience in the Arts.

Marc Reyes is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. He received his B.A. in History from the University of Missouri and his M.A., also in History, from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. His research investigates the United States and its interactions – diplomatically, economically, and culturally – with India. As a 2016 graduate intern, Marc is excited to gain additional experience working in a university archive and will be exploring the history of the Black Experience in the Arts course here at UConn as well as the broader movement of 20th century black expression in the arts.