Music from the film Beat Girl, 1960. From the Ann Charters Papers

Opening credits for the film:

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog

The New England Limited, better known as the White Train, or Ghost Train, which traveled from New York to Boston on the Air Line Division (formerly the Boston & New York Air Line Railroad) of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad in the early 1890s. Leroy Roberts Railroad Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Let’s get on board to celebrate National Train Day on Saturday, May 11! Amtrak organizes this event to celebrate the ways trains connect us all and to learn how trains are an instrumental part of our American story.

We here in the Railroad History Archive in Archives & Special Collections are celebrating this day by enjoying the rich resources in the collection that document how the railroad was pivotal to the lives of the people of New England in the Golden Age of Railroads in the late 1800s. This photograph shows the New England Limited on the Air Line Division, formerly the Boston & New York Air Line, which was built to provide a direct route diagonally across the state of Connecticut to connect the important financial centers of New York City and Boston. At the time this photograph was taken, in the 1890s, the B&NYAL was taken over by the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad and then known as the Air Line Division. The New England Limited reminds us of a time when luxurious trains were ridden by the Gilded Era’s captains of industry.

Enjoy National Train Day at a station near you! For more information about the celebrations, visit http://www.nationaltrainday.com/s/#!/

[slideshow_deploy id=’3736′]

In the early 1950s the New Haven Railroad phased out use of its steam fleet in favor of its electric and diesel locomotives. Shown here is a menu and photographs taken on an excursion trip from Boston’s South Station to New Haven, Connecticut, through the route of the old New York & New England Railroad with stops in Willimantic and New London, Connecticut. The photographs were taken by Seth P. Holcombe and Ralph E. Wadleigh, both of whose photographs we hold in the Railroad History Archive.

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

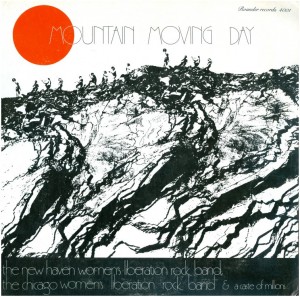

The Alternative Press Collection contains a series of LP (long-play) record albums by female musicians of the twentieth century whose music reflects the first and second waves of the women’s liberation movement. Two of these LPs are the post-first wave Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues LP and the second wave era New Haven and Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Bands’ Mountain Moving Day LP. Through the use of powerful, explicit lyrics and the moving techniques of blues and rock music, both LPs grapple with the issues of women’s rights, equality, and activism. They are timeless, auditory representations of the turbulent social contexts from which they came, and as such, they represent the century-long development of women’s rights awareness.

Volume 1 of the Mean Mothers Independent Women’s Blues album was produced in 1980 by Rosetta Reitz of Rosetta Records in New York, New York. According to Duke University Libraries’ Inventory of the Rosetta Reitz Papers, Reitz was a feminist writer, lecturer, and owner of Rosetta Records, which produced re-releases of female jazz and blues musicians’ songs from the early twentieth century. The LP’s gatefold cover, as mentioned by Graham Stinnett, the Curator for Human Rights Collections, contains biographical information about the female blues singers of the 1920s-1950s who are represented on this album.

Also, according to other content on the gatefold, the title’s term “mean mother” is meant as a compliment to all women, including those represented in the album, in that it is

a positive view of an independent woman, granting her the regard she deserves as one who will not passively accept unjust or unkind treatment.

The gatefold also states that these female singers were not just mourning lost love “in spite of the historic stereotyping imposed on them”, but were actually exploring every aspect of life through their music. These songs were created after the first historical wave of the women’s liberation movement ended in 1920, the year in which women were finally granted the right to vote. Yet despite the creation of this Constitutional amendment, the issue of women’s equality remained contentious. This is apparent when listening to the Mean Mothers album, which contains sixteen songs in total. For instance, Bessie Brown’s 1926 “Ain’t Much Good in the Best of Men Nowdays” laments that “married men have a tendency to roam,” while Bernice Edwards’ 1928 “Long Tall Mama” righteously claims that she is her own, independent woman and shall stand tall against adversity from men and other people in her life. On side B, Lil Armstrong’s 1936 “Or Leave Me Alone” ends with a long bluesy musical accompaniment, adding to the strength of the piece, much like Gladys Bentley’s deep, strong voice does in her 1928 song “How Much Can I Stand?” on side A.

Years later, during the second wave of the women’s liberation movement, The New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band collaborated to create their 1972 nine-song album entitled Mountain Moving Day through Somerville, Massachusetts-based Rounder Records. The second wave was characterized by similar social issues pertaining to women’s rights but with particular regard to women’s equality in the workplace and a woman’s right to choose.

A woman’s right to choose is dealt with in the New Haven band’s “Abortion Song” in which Jennifer Abod and her accompanying vocalists demand for their right to choose singing, “Free our sisters; abortion is our right.” Their frequent use of “sister” works to establish a common sense of sisterhood between themselves and other women. This term is also heavily used in “So Fine” as in the lyric “Strength of my sisters coming out so fine.” While the New Haven band’s songs deal more with female sexuality, the Chicago band’s songs work to oppose stereotypical women’s gender roles in songs such as “Secretary” and “Ain’t Gonna Marry.”

Ultimately, these female bands produced music in a similar vein as their jazz and blues predecessors indicating their intent to develop and maintain a nationwide women’s rights consciousness that is rooted in the past century and yet relevant today.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern

Last evening, I had the pleasure of meeting Fred Ho and hearing him speak at the book signing for Yellow Power, Yellow Soul: the radical art of Fred Ho, co-edited by Roger N. Buckley and Tamara Roberts, University of Illinois Press. In attendance was filmmaker Steven De Castro who has made a video showcasing Fred Ho’s original clothing designs currently on exhibition at the Knox Gallery, Harlem, New York. One of the many ways Fred Ho expresses himself. Check it out.

Carey MacDonald is an undergraduate Anthropology major and writing intern. In her blog series Through the Lens of an Anthropologist, Carey analyzes artifacts found in the collections of Archives and Special Collections.

The Beat poets characterized themselves as non-conformists who dismissed the growing materialism of 1950s American society in order to lead a freer, more spontaneous lifestyle. The poetry of Jack Kerouac reflects the Beat ethos, and it is within the collection of spoken word records that we find several LP albums on which Kerouac recites his own poetry to the tune of music.

Poetry for the Beat Generation is the result of the 1959 collaboration of Jack Kerouac and composer Steve Allen under New York’s Hanover-Signature Record Corporation. According to the LP’s jacket, this recording session lasted only an hour, as decided by both Kerouac and Allen who felt that this first, improvised recording sufficed – and it certainly did. Their unusual collaboration illustrates through words and music the curious life of the nonconforming individual. In “October In The Railroad Earth” Kerouac warbles about the many different people he sees in the diverse city of San Francisco. This poem is like Kerouac’s own sociological study: he juxtaposes the rushing commuters with newspapers in hand with the roaming “lost bums” and “Negroes” of the “Railroad Earth.” Kerouac furthers this theme of dualism when he remarks about things as ordinary as the movement of day to night and from sunny, blue sky to deep blue sky with stars.

Despite this thematic duality however, it is apparent that Kerouac does not mean to draw distinctions between the groups of people he observes. Instead he familiarizes himself with all sorts of people, breaks down the social divisions separating them, and lives among them: “Nobody knew – or far from cared – who I was all my life, 3,500 miles from birth, all opened up and at last belonged to me in great America.”

While “October In The Railroad Earth” is comprised of his momentary observations of the world, Kerouac’s recitation makes these observations inherently complex and compelling. The unique combination of his deep Lowell, MA accent with his precise word placement, expressive diction, and comical use of onomatopoeia makes this particularly vivid poem grab the attention of and resonate with the listener. Kerouac also tends to end his phrases with an upward inflection instead of dropping the last word to give pause to his thoughts. This is indicative of the almost never-ending stream of consciousness that runs through his mind, just like what each of us experiences every day.

Steve Allen’s improvised jazz piano accompaniment further enhances the potency of Kerouac’s recitations in that it reinforces the tone of the poem. In the case of “October In The Railroad Earth,” Allen’s rifts become fast and exciting when Kerouac discusses the busy commuters and then mellow out when day becomes night and when Kerouac comments on California’s “end of land sadness.”

“The Sounds of The Universe Coming In My Window” also reflects on an individual’s everyday sensory experiences, such as listening to the humming of aphids and hummingbirds or marveling at the trees outside. Allen’s piano and Kerouac’s alliteration and echo amplify the “sounds of the universe” described in this poem.

The somber piano accompaniment on “I Had A Slouch Hat Too One Time” establishes the wistful tone of Kerouac’s poem in which he laments that perhaps he does not belong with the Ivy League men of New York City who wear slouch hats and Brooks Brothers slacks and ties. Instead, on top of a now whimsical piano melody, he tells a (most likely) fictional tale about consuming drugs in the bathroom of a store in Buffalo, NY and then proceeding to steal a man’s wallet and begin a shoplifting spree. This poem clearly reflects the non-conforming values of the Beats and calls into question the value of the posh lifestyle of the men described in the poem.

Jack Kerouac and Steve Allen’s Poetry for the Beat Generation effortlessly reveals the dissenting ideals of the Beats, and across the span of American history we see a similar pattern of social disdain for the status quo.

Carey MacDonald, writing intern

Dr. Lisa Sanchez Gonzalez, associate professor in UConn’s English Department, has published a new book on Pura Belpre, the storyteller, author and librarian at New York Public Library who brought Puerto Rican folklore and the needs of bilingual children to light. In addition to extensive biographical information about Belpre and a selection of pictures, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez has included 32 of Belpre’s stories and 12 essays. The essays range from such topics as “The Art of writing for children” to “Library work with bilingual children.”

Cover, The Stories I read to the children: the Life and writing of Pura Belpre, the legendary storyteller, children’s author, and New York Public Librarian by Lisa Sanchez Gonzalez (New York : Hunter College, 2013).

One of Belpre’s delightful stories that Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez has selected for inclusion is “The Parrot who liked to eat Spanish Sausages.”

Once there was a parrot who liked to each Spanish sausages. Every day he would saunter into the kitchen, watch for the cook to leave for a few minutes, then snatch the Spanish sausages from the pot and saunter out before she came back.

At last the cook became suspicious and decided to watch the parrot. One day she hid behind the kitchen door and waited for the parrot to come. She had placed on the table a pot of vegetables with a string of sausages, as she often did before she lit the fire.

By and by the parrot came sauntering in. He went straight to the table, lifted the pot’s lid, took out the string of sausages, and made short work of them. Then off he sauntered again.

The cook said not a word. But later on, when she had placed the pot on a low fire, and the water was lukewarm, she picked up the parrot and poked his head into the pot. The parrot lost all of his head feathers and never again snuck into the kitchen to lift the Spanish sausages out of the pot.

One day a very important guest arrived to visit the family. And, as he often did, he overstayed his visit. Since it was time for dinner the family invited him to eat with them. The guest accepted graciously. While they ate, the parrot sauntered into the dining room. He circled the table twice, then flew up and sat on the guest’s shoulder. Suddenly he noticed that the guest’s head was completely bald. “So,” the parrot cried, “you too like to eat Spanish sausages!” And laughing and screeching the parrot flew out of the room.

Dr. Philip Nel’s newest work, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature, was published in September of 2012 by the University Press of Mississippi. This book is the culmination of years of work to bring to light the lives and times of the man who created Harold and the purple crayon and the woman who, with Maurice Sendak, created A Hole is to dig. Over the course of their marriage and collaborations, they created over 75 books and influenced some of the best in the business, including Chris van Allsburg who thanked Harold and his purple crayon in his Caldecott acceptance speech in 1981. Nel points out that while Krauss and Johnson were “never quite household names…Their circle of friends and acquaintances included some of the important cultural figures of the twentieth century.” (pg.7) This impeccably researched work which literally took Nel a decade to write, is arranged in 28 chapters, with extensive notes, bibliography, index and illustrations, some reprinted from published works and some from the three dozen archives he visited including the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. In his epilogue, Nel writes, “Crockett Johnson shows us that a crayon can create a world, while Ruth Krauss demonstrates that dreams can be as large as a giant orange carrot. Whenever children and grown-ups seek books that invite them to think and to imagine, they need look no further than Johnson and Krauss. There, they will find a very special house, where holes are to dig, walls are a canvas, and people are artists, drawing paths that take them anywhere they want to go.” (pg. 275)

Congratulations, Dr. Nel, on an exceptional work of scholarship.

Philip Nel, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss (Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2012). ISBN 978-1-61703-624-8. EBook 978-1-61703-625-5.

In his third blog installment, Glastonbury teacher and writer David Polochanin, recipient of the James Marshall Fellowship, shares two of his original poems after reading poetry in the Dodd Collection, from the Joel Oppenheimer and Robert Creeley papers.

Blog post 3: On Poetry

“Cartography” and “Celebrating the Peace” by Joel Oppenheimer (Joel Oppenheimer Papers, Box 11, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries). All rights reserved. No unauthorized reproduction allowed by any means for any reason.

3.20.13

Who would have

thought that

these papers,

with their typewriter

ink fading,

would see the

light of day

again, let alone

on this windy

Wednesday morning

in March?

When the poet

fashioned these words

40 years ago

they were

nothing special,

drafts scattered

in the author’s mind,

printed in a cluttered office,

gathering on the shelf

and the desk top,

in piles on the floor

against the wall,

and others in a stack

on the sill

beside a cactus.

The plant

(and the author)

have long since died

but today

I open a manila

folder and the poetry

comes alive, quite

a miracle, actually.

His words of reflection

and longing, poems

commemorating seasons,

and scenes

in New York City

that the poet likely

saw each day, planes

rising above the

Financial District,

papers blowing

on the sidewalk,

a bird that spent half

its morning jumping

from branch to branch

in a single tree

as a stream of taxis

formed one line

from here

to Central Park,

all of them turning at once,

then disappearing on

behind a monument

when I close this folder

and open the next.

“The Epic Expands” by Robert Creeley (Robert Creeley Papers, Box 2:Folder 48, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Libraries). All rights reserved. No unauthorized reproduction allowed by any means for any reason.

Sipping A Coke

Back when I was a kid

we used to sit on a porch

and sip Coke.

The parents sat in

rocking chairs,

holding their drink

in a bottle;

the young ones sat

on the concrete steps

flicking with their non-

drinking hand

the tiniest of pebbles

and the sun sat

motionless

in the sky.

We sipped it together.

We sipped it because

it was good. People

didn’t die because

of soft drinks, then.

No one developed

an addiction to caffeine

and diabetes

wasn’t a problem.

Having this drink allowed

us to chat about life,

about the dog’s laziness,

how the garden

was coming along,

and there was

a baseball game

on the radio

Saturday night.

Yes, those afternoons

had some kind

of timeless element.

I can still taste

the sweet soda

in my mouth

and I wonder

to this day

as I read this poem

what that

is all

about.