[slideshow_deploy id=’4475′]

Kirin J. Makker is an Assistant Professor of Architectural Studies at Hobart William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York, and the recipient of a 2014 Strochlitz Travel Grant. Travel Grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars and students to support their travel to and research in Archives and Special Collections. Part of the following essay also draws on materials at Winterthur Library, where this year Dr. Makker is also being supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities residential fellowship. To learn more about the book she is working on, please go here.

I went to Archives & Special Collections of the University of Connecticut Libraries to spend a couple of days sifting through the records of the E. Ingraham Company. I’m working on a book about the history of small town development when it boomed around 1900 and a major part of my research methodology involves following the trail of company goods right at the moment big capitalism really spread its wings (see blog The Myths of Main Street). My hope is to track where a handful of companies sold their goods in order to describe a product’s national distribution, and hence its availability across small town America. I have found, and my research will argue, that one of the reasons that small town America is such a consistent idea in the nation’s cultural language is that the goods exchanged there had both local and national parameters. Some of this research has had to do with companies that literally produced small town America: the storefronts, the brick-making machinery, the lamp posts. But other parts of the research is about the everyday objects that were sold in small towns, and how most of them during the period of small town America’s boom were not made locally or even regionally. The retailers were locals, but the items for sale on Main Street were typically sourced from manufactories or large distributors in cities.

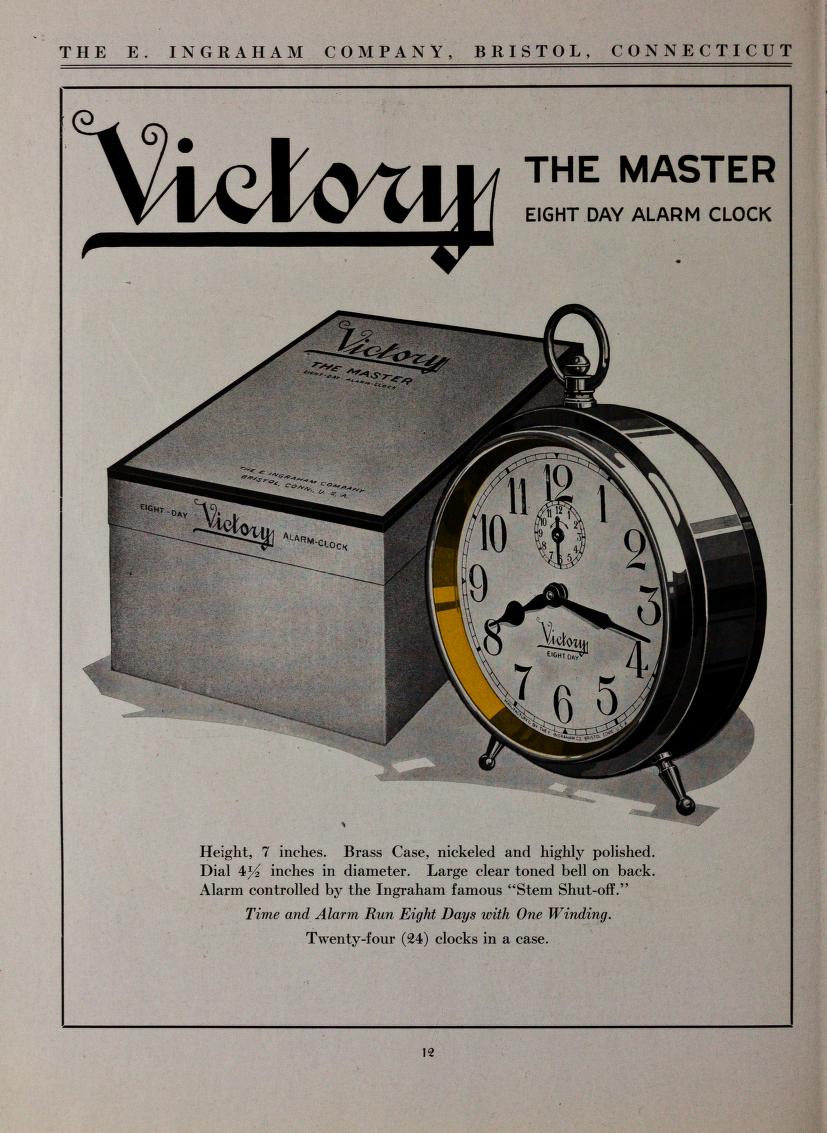

For example, a $2 watch made by the E. Ingraham Company in 1898 was made in Bristol, Connecticut but was sold on several thousand Main Streets all across America in general stores or small jewelry shops. Ingraham was after the mass market that the very successful company Robert H. Ingersoll had been selling to. Ingersoll had shrewdly introduced a $1 pocket watch, the “Yankee,” in 1892, stumbling into an enormous mass market of working- and middle-class consumers interested in owning timepieces they could afford.

Although Ingraham couldn’t make a quality watch for that little (the Ingersoll watches, not surprisingly, were cheap but not known for quality), they did start making a $2 watch by 1900 and these sold quite well, judging by how long they produced this watch (until the 1950s). Yet, when I dug around the Ingraham Company archives in Archives & Special Collections, I had some trouble finding records to support their efforts to take a share of the Ingersoll Yankee’s market.

As I said, I set out to spend all my time on the Ingraham Clock Company archive. However, it turned out that what I was really hoping to find within my time period (1870-1930, Main Street’s ‘boom period,’ so to speak), wasn’t so easy to cull. I had set out to identify names and locations of retailers who ordered Ingraham watches for their shops on Main Streets in towns all over the country. Or possibly find advertising by the company that included testimonials from retailers in small towns. I have found these types of testimonials for Elgin watches of the period, so I was hopeful. However, most of the Ingraham Company’s order records in Archives & Special Collections show sales to large distributors in cities. In addition, most of the records in the collection were from the 1940s and 50s (just the luck of what records survived, unfortunately). I did find contract letters with Sears from the 1930s, in which the mega-retailer agreed to uniquely market Ingraham watches in their stores and catalogs. But I needed letters with Sears or Montgomery Ward from around 1905 or more information about the distributors who bought $2 watches in large volume and then re-sold them in small batches to shopowners in the nation’s towns. That information may or may not be available in any archives, so in the end, the Ingraham $2 pocket watch story might not make it into the book.

However, as typically happens for me, as soon as I turn my attention away from one enticing collection, I find myself in the midst of a host of material that suits some other aspect of the book research. (Nothing, I tell you, NOTHING beats the fun of serendipity in the archives!)

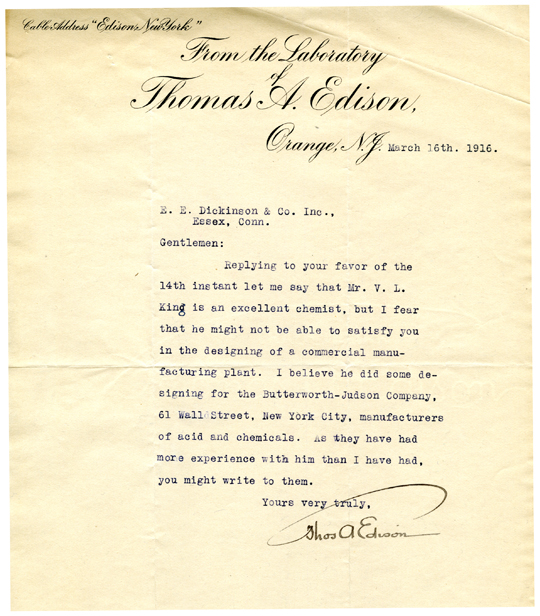

What did I find? A glorious collection of ephemera and sales records for the E.E. Dickinson Witch Hazel Company of Essex, Connecticut. One of the chapters I’m writing is on the variety of goods and services related to a townsperson’s health, all of which they could get on Main Street. There was quite a bit of overlap between what was a “good”, a “service” and also a ways to participate in community life in the many shops and offices in downtown small town America between 1870-1930. For example, one might go to the town druggist to purchase a prescription from a local doctor, a box of candy, or sit at the soda fountain and gab with friends over a strawberry fizz. Barber and beauty shops were where one got one’s haircut or styled, but also where one socialized with a gendered group of residents. Doctors were where one received diagnoses and health recommendations, but also where one might purchase a drug remedy (many physicians made their own drugs during the early part of my period of study). I’m interested in looking at how Americans living in small towns attended to their health needs because understanding healthcare history before drug and health insurance, medical malpractice, and managed care may be valuable for understanding our contemporary struggles with the industry. Or at the very least, this history offers an interesting comparison to the practices and standards the current day.

The story of Dickinson’s Witch Hazel fits right into this chapter because it was a factory-produced astringent that became an everyday remedy for minor ills. It was sold all over the country in drugstores and used extensively in small town doctor’s offices. And this time, I found records that show national distribution. For example, during the mid-1920s there were many letters between Dickinson executives and the Druggist Supply Corporation (DSC). The DSC was made up of retailers across America, many of which were located in small towns (Fresno, CA; Peoria, IL; Ottumwa, IA; Burlington, IA; Fort Wayne, IN; Rock Island, IL among many others). By working with that organization, Dickinson assured that they would get their product into those shop owners’ hands.

There were also several large company scrapbooks with hundreds of ads, letters from happy vendors, testimonials, and the like. For example, there was a letter from the owner of a drug store in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He was thanking the Dickinson Company for sending him a set of booklets to give out to his customers with their purchase of a bottle of Witch Hazel. With his letter of thanks, he included a clipping from the local newspaper which documents his announcement of the Witch Hazel booklet’s availability. He also noted that he gave a bunch of the booklets to a teacher at a nearby rural school for their students.

I could go on and on, but you’ll have to wait for the book. Overall, my visit to Archives & Special Collections was a success, both in terms of clarifying the role of Ingraham in the book and adding to my health-related goods and services chapter. [KJM]