The current political climate has re-invigorated discussions regarding advocacy as well as boosted interest in the affairs of both local and state government. It is fortuitous, then, to be working on the collected papers of Phyllis Zlotnick (b.1942-d.2011), who was a pioneering advocate for the civil rights of disabled people in Connecticut. Her collection of personal papers centers primarily on her work as a lobbyist for legislation pertaining to disabled populations. Reading through transcripts of her speeches, correspondences, and publications reveals a rich life of political activism, intellectual engagement and staggering patience.

The current political climate has re-invigorated discussions regarding advocacy as well as boosted interest in the affairs of both local and state government. It is fortuitous, then, to be working on the collected papers of Phyllis Zlotnick (b.1942-d.2011), who was a pioneering advocate for the civil rights of disabled people in Connecticut. Her collection of personal papers centers primarily on her work as a lobbyist for legislation pertaining to disabled populations. Reading through transcripts of her speeches, correspondences, and publications reveals a rich life of political activism, intellectual engagement and staggering patience.

Born with muscular dystrophy, Zlotnick used a wheelchair for most of her life. In defiance of the convention at the time, Zlotnick’s parents Sidney and Marion refused to institutionalize her because of her disability. Zlotnick’s education was an uphill battle for Sidney and Marion as well, having to picket the Hartford Board of Education for enrollment into a special education class, and needing to participate in her Portland High School classes via speaker phone. Despite these isolated experiences, she graduated with honors from Portland High School in 1960. Six years after her high school graduation Zlotnick would be hired as a receptionist at the Hartford Easter Seal Rehabilitation Center, a job that would prove to be a formative time for her developing acumen in advocacy.

Zlotnick’s work with the Hartford Easter Seal Rehabilitation Center and  The Easter Seal Society of Connecticut brought her in contact with June Sokolov, a trailblazer for increasing access to occupation therapy within Connecticut. Sokolov’s work proved to be a powerful influence and inspiration for Zlotnick throughout her life. The Zlotnick papers include a large collection of Sokolov’s work, papers written, as well as speeches given, and correspondences made to cultivate awareness on the effectiveness of occupational therapy as a discipline. The commitment to advocacy and empathy within Sokolov’s works has a clear influence on the directions and writings of Zlotnick herself.

The Easter Seal Society of Connecticut brought her in contact with June Sokolov, a trailblazer for increasing access to occupation therapy within Connecticut. Sokolov’s work proved to be a powerful influence and inspiration for Zlotnick throughout her life. The Zlotnick papers include a large collection of Sokolov’s work, papers written, as well as speeches given, and correspondences made to cultivate awareness on the effectiveness of occupational therapy as a discipline. The commitment to advocacy and empathy within Sokolov’s works has a clear influence on the directions and writings of Zlotnick herself.

At the start of the nineteen seventies, Zlotnick began to be an active presence for increasing awareness about architectural barriers to disabled populations in Connecticut. This start to advocacy work would see her contribute repeated testimony before the Connecticut General Assembly, work as an aide to House Speaker Earnest Abate, and eventually be called upon for her input in the Americans with Disabilities Act in the nineteen nineties. The Zlotnick papers offer an insight into the process of struggling to be heard in legislative and civic meetings, getting laws passed, and then fighting to have those laws enforced and implemented. The struggles that took place to have the Connecticut legislature pass laws for disabled individuals to have access to buildings and sidewalks involved long struggles for implementation as well as for enforcement. Zlotnick summarizes the challenges of advocating for equality in her talk entitled “Victory in Pursuit of Patience”,

It’s a seemingly never ending task for recognition of rights; of demonstrating the inappropriateness of exclusionary policies. There will always be those who are trying to undo or dilute the progress, people who repeatedly have to be educated and reminded of man’s inhumanity to man. We must keep going until we achieve full equality and integration.

(“Victory in Pursuit of Patience” c. 1992).

One of the most striking features of Zlotnick’s writing is the vulnerability within it. In her writing one reads not just how architectural and attitudinal barriers (to borrow one of Zlotnick’s own phrases) impact her on a physical and emotional level, but how the legibility of vulnerabilities in disabled populations reminds many with able bodies of the precarious nature of their own mobility, cognition, and autonomy. In a transcript of Zlotnick’s speech to the United Cerebral Palsy Association of Connecticut in 1974 she writes, “We [disabled people] represent a psychological threat – the average person is afraid of illness and by accepting us he must also accept his own potential for disability.” Zlotnick engages with these overlapping vulnerabilities in her testimony before the State and Urban Development Committee in 1978,

One of the most striking features of Zlotnick’s writing is the vulnerability within it. In her writing one reads not just how architectural and attitudinal barriers (to borrow one of Zlotnick’s own phrases) impact her on a physical and emotional level, but how the legibility of vulnerabilities in disabled populations reminds many with able bodies of the precarious nature of their own mobility, cognition, and autonomy. In a transcript of Zlotnick’s speech to the United Cerebral Palsy Association of Connecticut in 1974 she writes, “We [disabled people] represent a psychological threat – the average person is afraid of illness and by accepting us he must also accept his own potential for disability.” Zlotnick engages with these overlapping vulnerabilities in her testimony before the State and Urban Development Committee in 1978,

Many of you know that great numbers of handicapped people can appear to testify or otherwise show support. You will not see that kind of demonstration today because I am taking a gamble, the biggest one of my life. Rather than trying to persuade you by intimidation through a sea of wheelchairs, I am going to rely on your intelligence and my personal credibility. Should pressure tactics by more powerful lobbies who oppose the handicapped, for whatever reasons, break down the members of this committee or another committee should these bills be given a change of reference then I will have led thousands of handicapped people to the slaughter by not having a demonstration today. I’ve opted for intelligence and wisdom rather than fear and intimidation – please don’t prove I overestimated you.

(Testimony Before the State and Urban Development Committee 1978).

My instinct is to want to push back against the characterization of a group of people advocating for civil rights as intimidating, but in her acknowledgements Zlontick addresses the apprehension of her audience before offering a connection of her own. This acknowledgement is not an act of apologetics, it recognizes the tacit agreement behind the circumstances of Zlotnick acting as an advocate alone. Both sides of the conversations should start a discussion with an awareness of what renders them vulnerable to one another. It is a penetrating insight that sees traction in all vulnerable populations, not just those with disabilities, and exhorts us to conceive of vulnerability as a commonplace to draw communities and identities together rather than build barriers between them.

Patrick Butler is a Ph.D. Candidate in Medieval Studies at the University of Connecticut; his areas of interest are in Middle English romance and depictions of violence and vulnerability. In addition to his graduate studies and work in Archives and Special Collections, he is a Modern Language Association Connected Academic Proseminar Fellow for the 2016-2017 academic year.

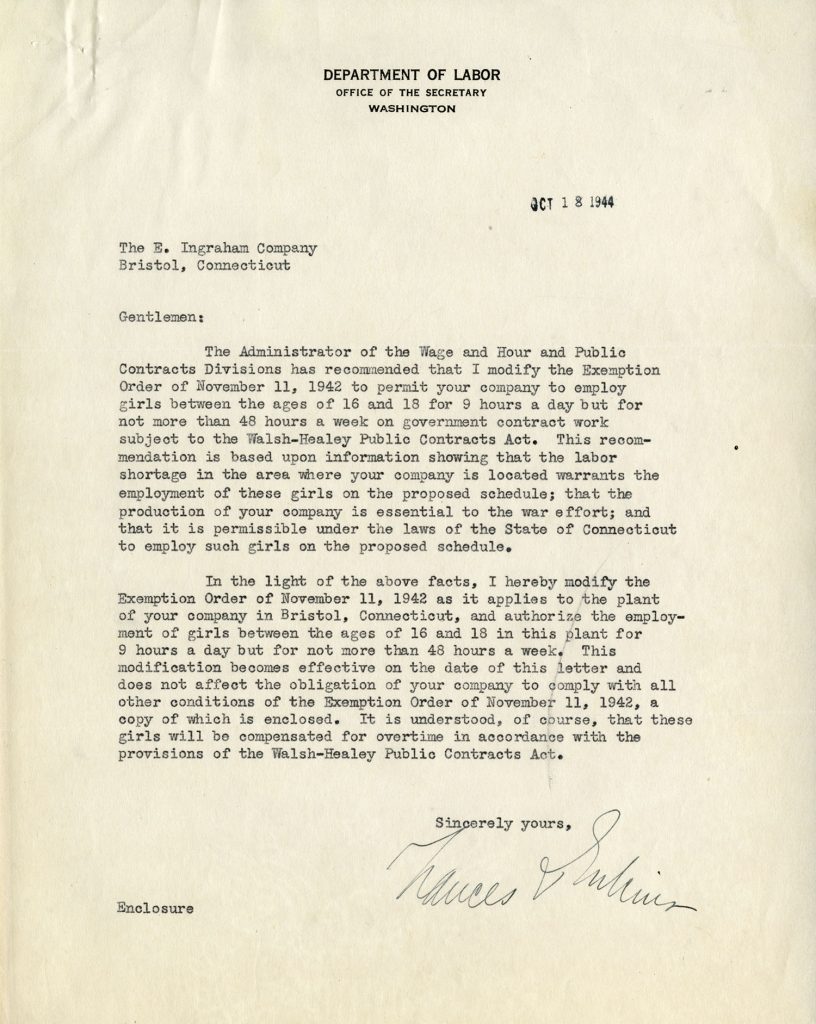

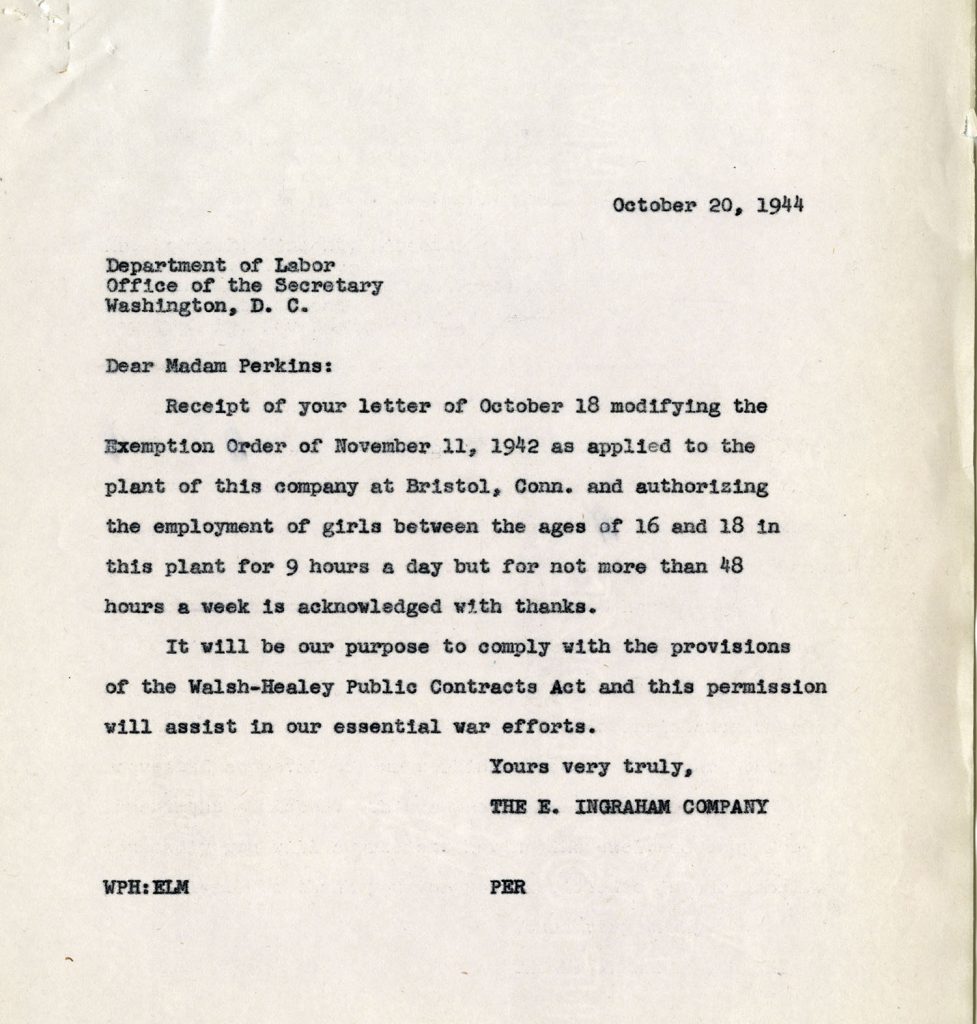

In late October 1944, famed U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins wrote to the E. Ingraham Company of Bristol, Connecticut. In her letter, she gave the company permission to employ girls between the ages of sixteen and eighteen for nine hours a day. Under an earlier federal regulation, young girls could only work for eight hours a day.

In late October 1944, famed U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins wrote to the E. Ingraham Company of Bristol, Connecticut. In her letter, she gave the company permission to employ girls between the ages of sixteen and eighteen for nine hours a day. Under an earlier federal regulation, young girls could only work for eight hours a day. cal women had long labored in the E. Ingraham Company’s Bristol factories. But World War II drew even more of them into the workplace. The relentless demand for munitions pushed company president Edward Ingraham to ask the federal government for a loosening of labor restrictions.

cal women had long labored in the E. Ingraham Company’s Bristol factories. But World War II drew even more of them into the workplace. The relentless demand for munitions pushed company president Edward Ingraham to ask the federal government for a loosening of labor restrictions.